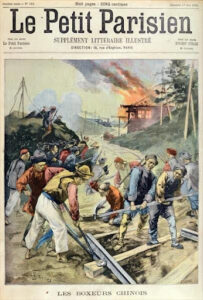

Image Source: The Chinese Boxers, Le Petit Parisien. Wikipedia Commons. 1900.

Introduction:

In this paper, I seek to explore and understand voices of opposition within the Russian Empire to colonialism in East and Central Asia, particularly within the context of the suppression of the Boxer Rebellion and the Russo-Japanese War in the Manchuria region. I examine Lenin’s “The War in China” and contrast it with imperialist thought, as well as the work of other socialists and writers during the time period. Sources on contemporary imperialist ideas in Russia included Sergei Witte’s statements about the Russian Empire’s economic and military goals in Asia, in addition to the ideas of contemporary diplomats, generals, and explorers, such as Fedor Martens and Mikhail Venyukov, on East Asian conflicts. Finally, I discuss other voices of dissent against imperialism during the time, including poets Aleksandr Blok and Yosano Akiko, and their relationship to Lenin.

Understanding contemporary imperialist thought and resistance in Russia in the early 20th century is important, given the significant global changes that occurred during the time period. In general, the early 20th century was a time of imperialism. Russia, however, at the time, was a “dying empire”; a decade later, it would become a socialist state and significantly change its “official policy” towards colonial and imperialist ideas. This change was brought about largely by Lenin’s interpretation of socialism, which he developed and explored through his political essays. Lenin composed much of his work and developed much of his socialist ideology, as global events, such as the Russo-Japanese War and Boxer Rebellion, challenged the Russian imperial government. As such, examining Lenin’s “The War in China” is essential to understanding the attitudes of the Russian autocracy, bourgeoisie, and proletariat at the turn of the 20th century.

The Russian and Chinese empires followed a significantly different trajectory for much of their history. In the 19th century, however, owing in part to Russia’s rapid westernization and expansion, the border between the two empires experienced increasing militarization. In the mid-19th century, Russia acquired significant tracts of Siberia and Asia following two treaties with the Chinese empire. During this time period, the Russian empire also explored opening trade with China.

In the late 19th century, the Russian empire began construction on the Chinese Eastern Railroad, part of the Trans-Siberian Railway, on land that it had previously acquired from China. At the time, the Chinese empire experienced an anti-foreign movement. In the early 20th century, the Boxers, a militant group of insurrectionists, resisted foreign influence in China with the support of the imperial court. Notably, the Boxers sabotaged the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railroad, attacking workers and dismantling significant portions of the railway. Their efforts cost the Russian imperial government tens of millions of rubles and significantly delayed progress on the railroad’s construction.

As a result, Russia sought to suppress the Boxer Rebellion, joining Japan, as well as several European powers, notably Great Britain, France, and Austria-Hungary in a military alliance. A great number of soldiers that participated in this conflict against China were citizens of the Russian Empire, and Russians were the first to enter Peking prior to the occupation of the city.

The conflict was also a very significant subject of discourse in the Russian Empire during the early 20th century. Russian newspapers published a great number of articles surrounding the events in China. In addition, the conflict was an area of major concern for Tsar Nicholas II and Sergei Witte, then finance minister of the Russian Empire. The construction of the Eastern Chinese Railroad as well as the creation of a “Russian City” in Manchuria (Dalian; Chinese: 大连) were in fact part of Witte’s plan for Russian involvement and economic development in China.

As a result, 20th century Russia saw a number of imperial officials, military figures, and writers provide political commentary on the empire’s involvement in Central and East Asia. Much of the material published during the time was in support of Russian imperial ambitions. However, especially during the Russo-Japanese War, voices of dissent emerged within Russia against imperialism and colonialism in Asia. Perhaps one of the most notable of these was that of Vladimir Illyich Lenin, who published articles in response to both the Boxer’s Rebellion and the Russo-Japanese War. Although his ideas were initially censored in Russia, they later became significant following the Russian Revolution. Examining Lenin’s ideas regarding the Boxer’s Rebellion and Russian imperialism in Asia in comparison with his contemporaries is especially important in understanding Russia’s transition from imperialism to socialism in the early 20th century.

Russian Official Policy and Involvement in China

In the early 20th century Russian Empire, the dominant viewpoint supported the expansion of Russia into China. Sergei Witte, as finance minister, sought this expansion mostly on economic grounds with the purpose of controlling trade in China. In the long-term, however, Witte believed in a complete acquisition of China by the Russian Empire. In 1900, he wrote in favor of an expansion into Southern China:

“Russia’s expansion into Southern China will prove to be an event of historical proportions; as such, there is no reason for us to pitch our fences in Manchuria. All of China should be included in our expansion policy as the bulk of China’s wealth is concentrated in the south. Therefore, all of China will be ours someday.”

Witte’s colonial ambitions in the Chinese Empire would be very significant towards shaping Russian involvement and military aggression in the region. During Witte’s tenure, the Russian Empire undertook several significant projects in Manchuria, including the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railroad. This led to the militarization of the region, as the Russian Empire had to defend the railroad from attacks by Boxers and robber gangs.

Russian colonialism in China was further supported by the popular notion that the Boxers and other ‘internal forces’ were taking advantage of the Chinese population. In the late 19th century, for instance, the Chinese Empire requested the Russian Empire end its occupation of Chinese Turkistan. In response, the Russian Empire attempted to deceive Chinese diplomats by offering the Treaty of Livadia, which ceded only part of the land along the Ili River. When the Chinese Imperial government refused to ratify the treaty, Fedor Fedorovich Martens, a Russian diplomat, wrote to then Tsar Alexander II that this refusal was the result of anti-foreignism in China:

“The military party, which forced the Beijing government to refuse to ratify the treaty signed in Livadia, obviously took advantage of the muted but deep unrest that had long gripped the population of China and was directed against foreigners and all European nations that had ever before concluded international treaties with China… The present misunderstanding would never have arisen … if the Chinese had not been forced to hate foreigners who constantly disrespect their most indisputable rights…”

In his analysis, Martens specifically places blame on the Chinese government for the failure of the Lividia Treaty. Despite the unfair terms of the treaty itself, Martens suggests that the underlying reason for the refusal of the Chinese Empire was its anti-foreign ideology and the promotion of this ideology among its people. Martens’ analysis likewise supports the idea that Chinese citizens, during the time period, were portrayed as ‘docile’ subjects with little of their own political agency.

Similar patronizing beliefs about Chinese civilization were likewise a factor that motivated Russian imperialism in China. In the early 20th century, “Asian backwardness” was a commonly held belief throughout Europe. For instance, Mikhail Ivanovich Venyukov, a Russian general, wrote that Russia’s success in its conquest of Central Asia will be decided by its “superior” civilization:

“We should succeed in Asia not due to our force of arms or by the large Russian population, or even due to economic and political superiority, but rather due to our moral and intellectual superiority. We have overlooked that of all the forces of conquest, the strongest is the exchange between the defeated and the victors in the field of intellectual development, as was the case in the Roman Empire. Despite our political contradictions with England, we have one common historical mission – to civilize the distant East.”

Similarly to other colonial beliefs, such as the racist ideologies that drove the conquest and subjugation of indigenous people in the Americas, the Russian Empire’s ideologies clearly placed the Chinese empire and its citizens in a position of inferiority. Venyukov’s writing shows that the Russian Empire’s colonization of China was not only motivated by economic and political factors, but also by a claim of Western superiority over the East. Importantly, Venyukov writes from the perspective of the Russian military, which implies the use of this ideology as a justification of the occupation of China.

Vladimir Illyich Lenin: Views on Colonialism and the Boxer Rebellion

Lenin’s article “The War in China” is expressly anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist, as well as a direct response to the Russian Empire’s official policy in Manchuria during the time. Lenin begins his argument specifically by referencing “Russia’s civilising mission in the Far East.” He then criticizes the Russian empire’s claim of “disinterest” in conquering China, comparing it to England’s actions in India and China. Lenin opines that every capitalist nation is a colonial one, and that the war in China is just another way in which the bourgeoisie are exploiting and benefiting from the lower class.

Lenin’s argument about the “Chinese War” stands in direct contrast to Witte, Martens, and Venyukov’s ideas. Firstly, throughout his article, Lenin criticizes anti-foreignism as a justification for occupation. He supports violence as a means of resistance, highlighting that the Boxer Rebellion is the result of previous European imperialism in the region. He further mocks the Russian Empire’s aim of “civilization” of the Chinese people, writing:

“They [Europe] began to rob China as ghouls rob corpses, and when the seeming corpse attempted to resist, they flung themselves upon it like savage beasts, burning down whole villages, shooting, bayonetting, and drowning in the Amur River unarmed inhabitants, their wives, and their children. And all these Christian exploits are accompanied by howls against the Chinese barbarians who dared to raise their hands against the civilised Europeans.”

Lenin also writes that these claims of “civilization” are part of a propaganda campaign on the part of the Russian press to silence opposition to the war and to create hostility between the Chinese and Russian people.

As discussed above, Lenin’s opposition to colonialism relies on the relation between what is considered “civilization” in the 20th century and capitalism, which he shows by examining European activity in China. In many of his other writings, Lenin further develops this idea, claiming that capitalism halts technological, societal, and economic progress. For example, in his article “Civilised Barbarism”, Lenin discusses the construction of an underground tunnel (The Channel Tunnel) between Britain and France. He states that members of the British bourgeoisie, who would lose business following the construction of the tunnel, are engaging in fearmongering, attempting to frighten the British people about a possible invasion. Lenin claims that this has led to a significant backlog on the construction of the tunnel. Notably, Lenin’s discussion regarding the role of the press in both cases is quite similar: he states that the bourgeoisie leverages their power over the press to further their colonial and capitalist ambitions.

In his discussion of the use of the press by the government to influence the people’s perception of the war, Lenin also writes about racism as a strategy to generate support for the war. He specifically cites that “the press is conducting a campaign against the Chinese; it is howling about the savage yellow race and its hostility towards civilisation.” Jinyi Chu, assistant professor in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University, argues that Lenin took an anti-racist socialist position in his essays on contemporary Asian issues. Chu notes that Lenin explicitly equates racism with capitalism; Lenin also believed that socialism and an end to racism were deeply related.

Notably, several other of Lenin’s contemporary socialist thinkers supported this viewpoint. For instance, Leon Trotsky, writing in opposition to the Russo-Japanese War, expressed a similar disdain for the use of racist propaganda by the Russian Imperial government. In his book “Our First Revolution”, Trotsky writes that racist propaganda in Russia was important to create a sentiment of nationalism throughout the empire:

“The aim of the response was thus clear: to turn the war into a national enterprise, to unite “society” and “the people” around autocracy…, to create an atmosphere of devotion and patriotic enthusiasm around tsarism… [the response] sought to kindle feelings of patriotic indignation and moral indignation by mercilessly exploiting the so-called treacherous Japanese attack on our fleet. It portrayed the enemy as insidious, cowardly, greedy, insignificant, inhuman. It played on the fact that the enemy was yellow-faced, that he was a pagan. It thus sought to evoke a surge of patriotic pride and disgusting hatred of the enemy.”

Here, Trotsky posits that the justification of imperial attitudes was essential in order to stabilize the position of Tsar Nicholas II and the bourgeoisie during the war. Much of this justification occurred through the press’ use of racist and nationalistic ideology to dehumanize and alienate Asian people.

In addition to his discussion of race, Trotsky states that religious discrimination was another target of propaganda. The press sought to contrast East Asians with the “typical” Russian person, portraying Chinese and Japanese people as pagan. Lenin emphasizes this tactic throughout his essay, mocking the Russian Empire’s “Christian unselfishness.” Comparing the Russian Empire’s actions in the region to historic cases of imperialism, Lenin also alludes to the Second Opium War, which he states was justified on religious grounds. Overall, the themes of race, nationalism, and othering that appear in both Lenin and Trotsky’s works not only support Chu’s argument that these topics had become very important to socialist thinkers, but they also suggest a paradigm shift in attitudes towards war and national identity.

In “War in China”, Lenin makes it no secret that his anti-colonial attitudes are an argument for the establishment of socialism in Russia. Throughout his essay, he seeks to agitate the ordinary person and position them against the government by bringing to light the governments’ wrongdoings. Lenin thus does not focus on the individual impact of war or its morality; rather, he puts the spotlight on government corruption as well as the impact of the war on the collective. In effect, Lenin writes a political criticism of predominant attitudes during the time, such as those held by Witte, Martens, and Venyukov, with the motive of advancing socialist ideas among the Russian people.

Literary and Humanistic Reactions to the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War, beginning soon after the Russian Empire’s suppression of the Boxer Rebellion, was likewise a major imperialistic conflict in East Asia in the early 20th century. In this case, however, both sides, the Russian and the Japanese Empires, waged war with the same imperial goal: to gain control of the Manchuria region. As per the discussion of Lenin and Trotsky’s writing above, the official policy of the Russian Empire during the Russo-Japanese War closely reflected that of the War in China. Yet, the scale of the war was far greater. In total, the war involved over one million soldiers on both sides and lasted over one-and-a-half years. The war did not only generate socialist opposition. In both Russia and Japan, writers and artists criticized the war, calling for an end to violence in the region. Critics differed from Lenin and Trotsky in that they took a more humanistic view of the war, taking the perspective of the “ordinary person.”

One notable voice of dissent from within the Russian Empire was Aleksandr Blok. At the start of the Russo-Japanese War, Blok published a short poem, aptly titled “War” (Russian: Война) in which he expressed his opinion about the inhumanity of violence. The poem depicts the horrors of the Russo-Japanese War, with the imagery of death and sinking ships, and also equates the war with “vengeful pride.” In the last four lines of his poem, Blok writes:

“Yet in the howling of the mighty storm,

In the dreams of the warrior and in his blood

Dwells the inspirer of the Furies,

And she sighs about Love.”

In this passage, Blok highlights the futility of war and its meaningless nature to soldiers. He directly states that the soldiers do not want to fight in the war and do not see the meaning in “revenge”.

In reality, Blok’s poem could be written about any war, something the author himself captures with his “generic” title. The poem’s pacifistic message, however, is important in the context of imperialist discourse in Russia, especially given Blok’s social status. Blok was born into the Russian intelligentsia and can be considered a part of the Russian bourgeoisie. Blok believed that war, in principle, was immoral, an idea that reappears in several of his later works. While his poem is not literally anti-colonialist, his rejection of the Russo-Japanese War could be certainly seen as discontent with Russian imperial policy. In fact, one of the central themes Blok explores in this poem is the meaningless nature of war to the ordinary person, an idea shared by Lenin in many of his political essays. Thus, Blok’s discontent towards the Russo-Japanese War implies a general shift in attitudes towards imperialism throughout all of Russian society, as even the bourgeoisie began to question the government’s policy in East Asia.

In the Japanese Empire, a similar trend could be seen in anti-war attitudes. Famous Japanese poet Yosano Akiko published a poem titled “Don’t Lay Down Your Life” (Japanese: 君死にたまふことなかれ). The poem was written to her brother, who had been conscripted earlier that year and sent to fight in the Russo-Japanese War. The poem is deeply personal to Akiko, who wishes for her brother to return home.

Importantly, Akiko dismisses Japanese imperialism. She instead emphasizes the personal and emotional toll of war. She writes:

“You were born into a long line

of proud tradespeople in the city of Sakai;

having inherited their good name,

don’t you dare lay down your life.

What does it matter if that fortress

on the Liaotung Peninsula falls or not?

It’s nothing to you, a tradesman

with a tradition to uphold.”

In this stanza, Akiko directly states that a person’s life is more important than the success of the Japanese military. This is quite significant, given the honor and significance traditionally attached to serving the Emperor in Japan. In fact, Akiko later calls into question the Emperor himself, writing that “The Emperor himself doesn’t go to fight at the front; others spill out their blood there.” This statement is remarkably similar to Lenin’s claims about the Russian autocracy and the bourgeoisie, who he states exploit and send the people to reinforce their position of power, such as by the suppression of violent resistance.

Nationalism was a significant driving force behind support for the war in both the Russian and Japanese Empires in the early 20th century. Both Blok and Akiko directly challenge the propaganda spread by both imperial governments to justify their colonial ambitions. Their ideas are not so much broad political statements, like Lenin’s works, but rather their personal beliefs, based on contemporary ideas about morality and personal experiences. Yet, their works are deeply intertwined with Lenin’s, as their resistance to imperialist ideas, such as those expressed by Witte, Martens, and Venyukov, set the stage for a period of significant political and ideological global change.

Not just ten years later, World War I changed the meaning of “War” forever. A few years later, the Russian Empire, which had been affected significantly by its losses in the Russo-Japanese War, experienced a revolution and became a socialist state. In subsequent years, it would challenge Lenin’s ideas about colonialism and imperialism. Still, Lenin, Blok, and Akiko’s writing continue to remain important in discussions of foreign policy and pacifism today.

Conclusion:

In this essay, I explored contemporary dialog in early 20th century Russia on colonialism and imperialism. I showed that Lenin, in his political essays on the Boxer Rebellion, adopted an anti-colonialist viewpoint, in response to contemporary imperialist ideas. For Lenin, anti-colonialism became synonymous with socialist resistance, while imperialism was synonymous with capitalism. Further, Lenin’s ideas overlapped with those of writers and poets of the time, many of whom were part of the intelligentsia. While Lenin’s critique was based on his political ideas, most contemporary writers who spoke out in criticism of the war did so on moral grounds. Yet, they all shared a similar disdain for imperialism. This growing anti-imperialist sentiment was paramount to the next several decades of world affairs.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

Akiko, Yosano. “君死にたまふことなかれ” [Don’t Lay Down Your Life]. Last modified 1904.

Blok, Aleksandr. “Война.” [War] Last modified 1905.

Lenin, Vladimir Illyich. “Civilised Barbarism.” Marxists. Last modified September 10, 1913. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1913/sep/10b.htm.

———. “The War in China.” Marxists. Last modified December 1900. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1900/dec/china.htm.

Martens, Fedor Fedorovich. Россия и Китай. N.p.: The printing house of I. Gaberman, 1881.

Trotsky, Leon. “ВОЙНА И ЛИБЕРАЛЬНАЯ ОППОЗИЦИЯ” [War and Liberal Opposition]. Marxists. https://www.marxists.org/russkij/trotsky/works/trotl103.html.

Venyukov, Mikhail Ivanovich. Россия и Восток. [Russia and China] Collection of Geographical and Political Articles. 1877.

Wells, David. “Three Russian Poems on the Battle of Tsushima.” Japanese Studies 11, no. 1 (1991): 85-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371399108521952.

Secondary Sources:

“Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Blok.” Britannica. Last modified November 24, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aleksandr-Aleksandrovich-Blok.

Anan’ich, B. V., and S. A. Lebedev. “Sergei Witte and the Russo-Japanese War.” International Journal of Korean History 7 (February 2005): 109-31. https://ijkh.khistory.org/upload/pdf/7_05.pdf.

“Boxer Rebellion.” Britannica. Last modified October 17, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/event/Boxer-Rebellion.

“China and the Trans-Siberian Railway.” 1870to1918. Last modified April 1, 2014. https://1870to1918.wordpress.com/2014/04/01/china-and-the-trans-siberian-railway/.

Chu, Jinyi. “Civilizational Myth and Class Politics.” Comparative Literature 75, no. 2 (2023): 140-52. https://doi.org/10.1215/00104124-10334490.

Egorov, Boris. “How the Russians captured Beijing.” Russia Beyond. Last modified August 23, 2021. https://www.rbth.com/history/334124-how-russians-captured-beijing.

Mitchell, T. J.; Smith, G. M. Casualties and Medical Statistics of the Great War. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. 1931.

Radchenko, Sergey. “What Are the Legacies of Sino-Russian Relations?” International Center for Defense and Security Estonia. Last modified June 6, 2023. https://icds.ee/en/what-are-the-legacies-of-sino-russian-relations/#:~:text=Whereas%20early%20encounters%20between%20Russian,of%20land%2C%20including%20the%20sizable.

“Russo-Japanese War.” Britannica. Last modified November 15, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/event/Russo-Japanese-War.

Semyonov, Yuri. Siberia, its Conquest and Development. (Baltimore, MD: Helicon Press, 1963).

Tikannen, Amy. “Ili crisis.” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Ili-crisis#ref1079985.