Hi guys 😀

This was my final project for GSS 206. Hope you enjoy <3

Here’s the link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ks3J5EZAzStoTrmUyqClR2IP8flwTcN0/view?usp=sharing

Spies of Empire/Empire of Spies

GSS206-NES204-THR214, Fall 2025

Hi guys 😀

This was my final project for GSS 206. Hope you enjoy <3

Here’s the link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ks3J5EZAzStoTrmUyqClR2IP8flwTcN0/view?usp=sharing

Looking back over my portfolio, I can see a clear progression in the way I think and write about travel literature, empire, and the figures we studied. My earliest post, the Yasmina playlist, was driven by empathy and atmosphere. My initial approach was to look for feeling and emotional resonance. As the semester continued, I began to shift my writing to focus more on examining power, especially with Gertrude Bell and Freya Stark. At the end, with Lawrence, I was more intrigued about the psychology of the spies we were studying.

One of my favorite ideas I developed this semester was presented in my “Bystander” blog post. Reframing Lawrence’s torture writing helped me confront something that his narrative often avoids: the uncomfortable representation of performance, trauma, and discipline that is embedded in his demeanor. I explored how the heroic silence was simply a form of survival strategy that could be linked to his internalized need for punishment and also just trauma from the past. I liked this idea because it helped me do a more complicated and human reading of Lawrence.

An important thing I was able to do through these blog posts and the midterm was experiment between analytic and creative writing. Creative writing, like Bystander, the Yasmina Playlist, and the play I wrote, allowed me to look at the spies’s travel writing as performative. They were constantly staging themselves after all, whether as experts, wanderers, diplomats, or heroes. I was able to question why these authors chose to present themselves in the way they did, which I have never done before in a class. Through analytic reading and writing, I was able to learn to read these texts with a specific lens in mind. Looking at the writing with all of these factors, like political structure and alliances, helped reframe it.

Going forward, I would love to know more about how people actually affected by these spies remembered these figures. A lot of what we read came from the Western world. But I would like to know how, say the local people of the past saw Gertrude Bell. I am also a sucker for psychoanalytic analysis, so I would love to see what psychologists think about some of these spies. Something else that would be interesting is to think about what these narratives would look like if they written today. How would Lawrence write about himself today?

I will be rewriting the torture part of Seven Pillars of Wisdom from the perspective of a bystander. The graphic scene is included in Chapter LXXX.

I stood near the wall, pretending to check the lantern, though there was nothing wrong with its flame. The others had already thrown the prisoner across the bench. He was frail—British, I presumed—with the grit he kept pressed between his teeth. His body buckled as they forced his wrists and ankles into place. I worked in these prisons, so I had seen beatings before, but they never made me feel this uneasy. Something about the way he clenched his jaw, as if bracing for pain he expected and almost welcomed, did not sit right with me.

Who is this man?

The corporal came back up the stairs with that Circassian whip he polished like a favorite blade. For a moment I thanked God that I was not on the opposing side. He snapped the lash by the prisoner’s ear. A clear taunt in regards to the impending lashing he was about to receive. The prisoner did not answer. He sharply breathed once and held still.

The first strike left clean streaks, bright and deep like fresh tracks on snow. He faintly counted them, as if insulting the corporal with his consciousness. The corporal grew angrier and the lashings got worse. I would turn away if it did not render me in contempt. His back trembled not only from pain, but from anticipation, a hint at the terror held just beneath the surface.

When he finally slid to the floor in a daze, he looked almost peaceful. As if he had drifted somewhere far away from the beating. I could not understand why this was so difficult for me to watch. Maybe it was the stubbornness he had or the way he remained so still.

Whatever it was, I felt ashamed to be standing there and simply being the bystander.

Rewriting this passage from the perspective of a bystander changed the emotional gravity of the scene. I particularly wanted to emphasize Lawrence’s quietness. In the original text, which is from Lawrence’s perspective, he framed silence as heroic endurance. I wanted to shift the perspective to someone watching these events unfold because I wanted to confront something that maybe Lawrence was not willing to see, which was how brutal, complicated, and practiced that response must have been. I do not want to sound Freudian, but this event of him getting whipped most likely did bring back memories of his mother hitting him. To me and other bystanders, the silence in Seven Pillars of Wisdom was giving old survival strategies that were resurfacing for Lawrence. Also, on the comment of the bystander assuming that Lawrence was British. I got that idea from the Gertrude Bell clip we watched, where she said “exploration is a British thing” or something along those lines. I decided to put my own spin on that.

*while writing this, I did take some creative liberties so this Freya is based on real Freya

If I had to choose a travel companion from our readings, I would pick Freya Stark herself. I do not think she would be pleasant company, but the discomfort would be instructive. I imagine u somewhere in contemporary Baghdad, a city she knew intimately in the 1930s, now transformed beyond her recognition.

We would share a talent for observation but diverge completely in what we do with it. Whereas Stark collected details about women’s jewelry and Bedouin customs, I would be watching her watch them. I would note her gaze even as she would be in casual conversation. She would probably find me frustratingly direct with the way I would keep asking her about her work with Stewart Perowne and Adrian Bishop. I would also ask her about those cocktail parties at South Gate while Iraq burned with nationalist fervor.

The tension would be palpable in the markets she once wandered through in disguise. She would want to show me the hidden corners she discovered, the nocturnal Ramadan celebrations she witnessed. There, I would keep pointing out the British Embassy, the old intelligence offices, and the sites of colonial violence. When she would try to romanticize the Bedouin “raw and traditional,” I would remind her of the cruel things she justified.

What we would have in common is curiosity. We both have a restless need to understand how societies work. Where her curiosity served empire, mine would serve its unraveling. She would probably recognize in me the same stubborn independence. But she would hate how I would use that independence to question everything she stood for.

The trip would end badly, I think. Maybe at one of those archaeological sites she loved to claim as “discoveries.” Those many ruins she bragged about visiting alone. I would ask her what gave her the right to “discover” places people had been living in for millennia. She would call me ungrateful, claiming that she had preserved so much knowledge. When we would part ways, we would each be convinced the other had missed the point entirely.

In the end, though, I would learn something valuable from traveling with her: how empire’s most effective agents are not the obvious villains, but the complicated and talented people who genuinely love what they are helping to control.

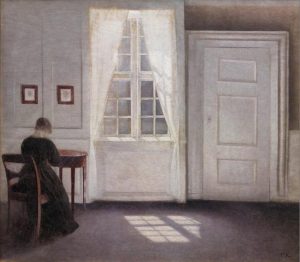

Interior from Strandgade with Sunlight on the Floor

By Vilhelm Hammershoi

Throughout the unit, I noticed a lot how Gertrude Bell had moments of seasonal depression as well as just regular depression. Specifically, in The Letters of Gertrude Bell Volume 1, she exhibited a great amount of seasonal depression while working in Basrah. The transition from being satisfied with her work in December to experiencing physical hardship, illness, strain, and depression in January is reminiscent of this painting and how the woman in it seems sad and reserved. The light in the painting fills the room but it somehow does not warm it which is similar to how the cold feels. Furthermore, when Bell talks about her feeling “limited” by her gender, it feels like how the woman in the painting is alone, cornered, and also “limited” in the way by the artist. I also imagine that the girl in the painting is writing and persevering, similar to how Bell had a sort of quiet endurance despite the inner fatigue she kept feeling when she worked.

Beyond her seasonal depression, Bell deeply mourns the loss of her lover Henry Cadogan. After his death, all her writing is filtered through a lens of grief. If you do a side by side comparison of The Letters of Gertrude Bell with Persian Pictures, you can see that her outlook of the beautiful regions she is visiting is much more grim. Like, in Persian Pictures, she says “Sunshine – sunshine! tedious, changeless, monotonous! Not that discreet English sunshine which varies its charm with clouds… here the sun has long ceased trying to please so venerable a world.” Bell is starting to hate the weather and environment she is in. Although she expresses similar distaste for the weather in the Letters of Gertrude Bell, it is not all encompassing. Just like the woman in the painting, Bell feels colder.

I often do readings while listening to sad playlists full of tragic love songs. While reading Yasmina, I found myself sympathizing with her even more because the music added an extra melancholic element. Her story moves like music, beginning with quiet innocence, swelling with passion, and ending in heartbreak and collapse. These five songs, for me, capture Yasmina’s journey.

This song reflects the way Yasmina begins: innocent, dreamy, and living her life as a shepherdess among the ruins. She doesn’t fully understand what’s coming, and when Jacques enters her world, she’s swept along almost without a choice. The line “Will you still love me when I’m no longer young and beautiful?” mirrors Yasmina’s fate. Jacques is captivated by her youth and beauty, but those qualities fade in his memory once he returns to France, leaving her devotion behind.

2. “Love Will Tear Us Apart” – Joy Division

Yasmina and Jacque’s love is doomed before it even begins. She even tells him it’s impossible for a Muslim girl and a French officer to be together. But instead of stopping, they give in, which makes their passion both beautiful and devastating. The song has the same feeling: you know the ending will be tragic, but you can’t look away. For me, the refrain “love will tear us apart” is exactly what happens when Jacques is reassigned. Reality itself rips their love apart.

3. “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” – Green Day

When Jacques leaves for his new post, Yasmina is left in total loneliness. The image that stays with me is her lying facedown in the gorge, immobilized by grief. She doesn’t rage or resist. She just repeats mektoub. That resignation matches the emptiness in Green Day’s song, where the singer walks a lonely road with no one by his side. Yasmina’s “boulevard” is the dusty plain of Timgad, but the isolation and drained hope are the same.

4. “Somebody That I Used to Know” – Gotye ft. Kimbra

This song reflects the cruelty of Jacque’s return. Yasmina still sees him as her Mabrouk, the man she loved and waited for, and she calls to him with joy. But Jacques, now married to a Parisian woman, treats her as nothing but a shameful past. Her outburst: “Why did you use all of your ruses… to seduce me, carry me away, and take my virginity? Why did you lie and promise to return?” This fits perfectly with the song’s bitterness about being turned into a stranger by someone who once defined your whole world. For Yasmina, love was life itself. For Jacques, it became disposable.

5. “Back to Black” – Amy Winehouse

The end of Yasmina’s story is the hardest to read, and Back to Black is the only song that fits. Yasmina spirals into illness, poverty, and prostitution, but even then she still clings to the memory of Jacques. Winehouse’s line “we only said goodbye with words, I died a hundred times” captures the endless mourning Yasmina embodies. The story’s final words, “Yasmina the Bedouin was no more,” echo the song’s raw finality. Both tell of women consumed by love that society never let them keep.