Synopsis:

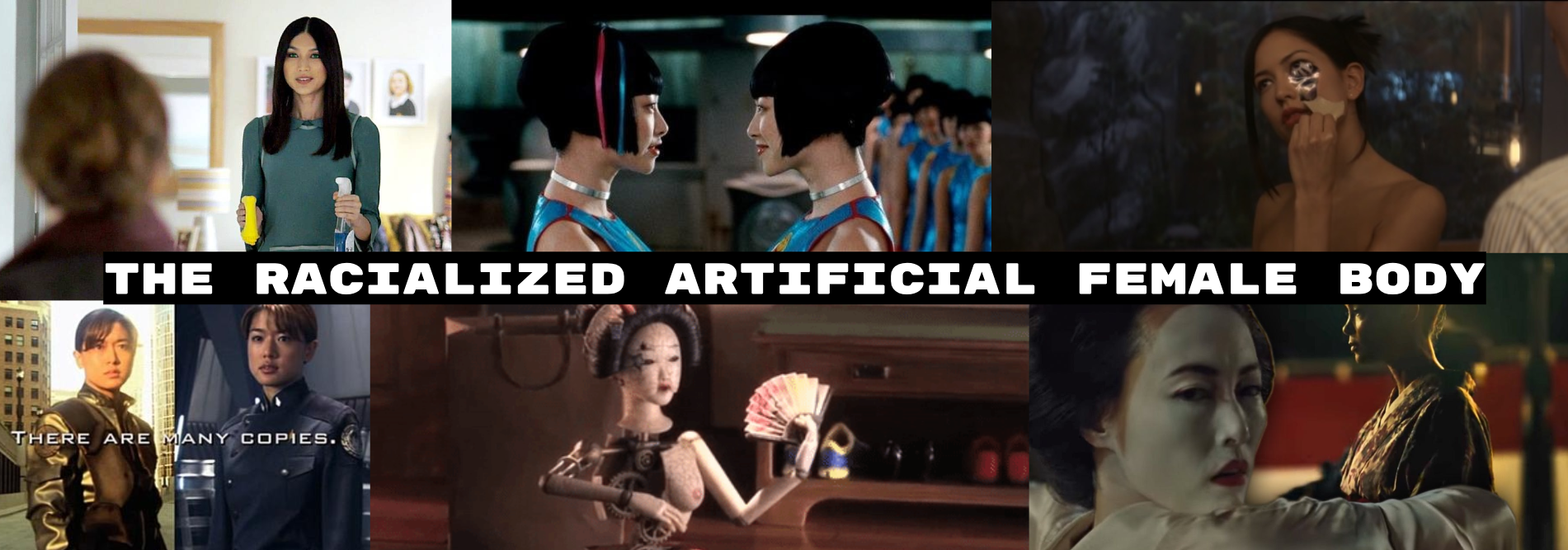

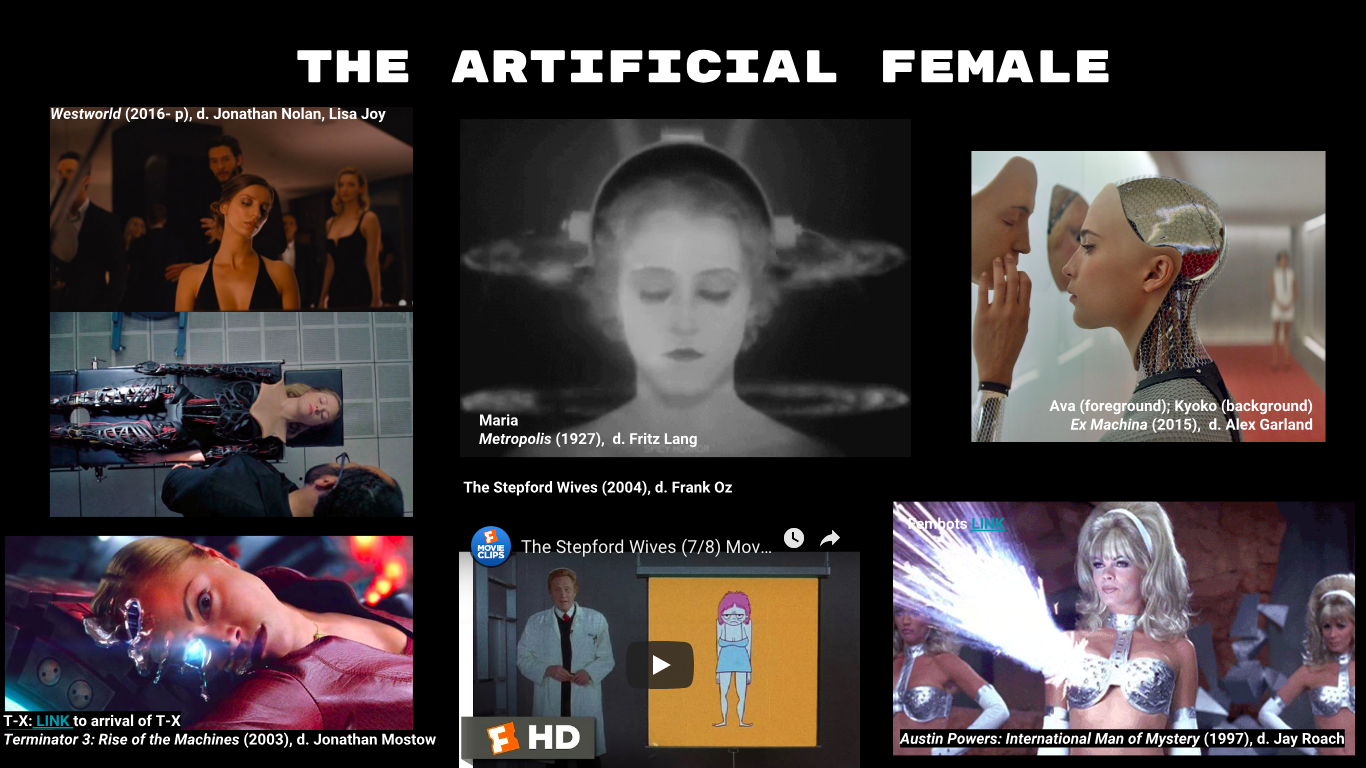

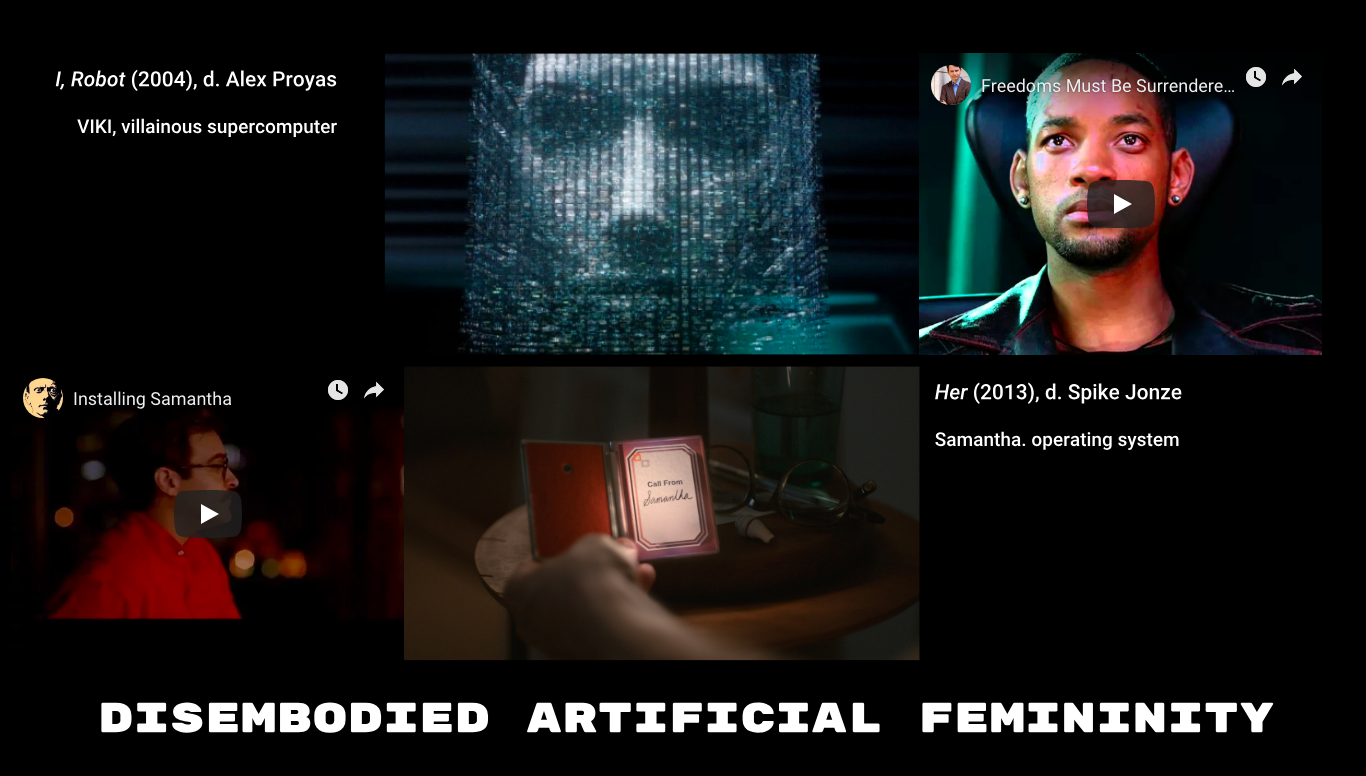

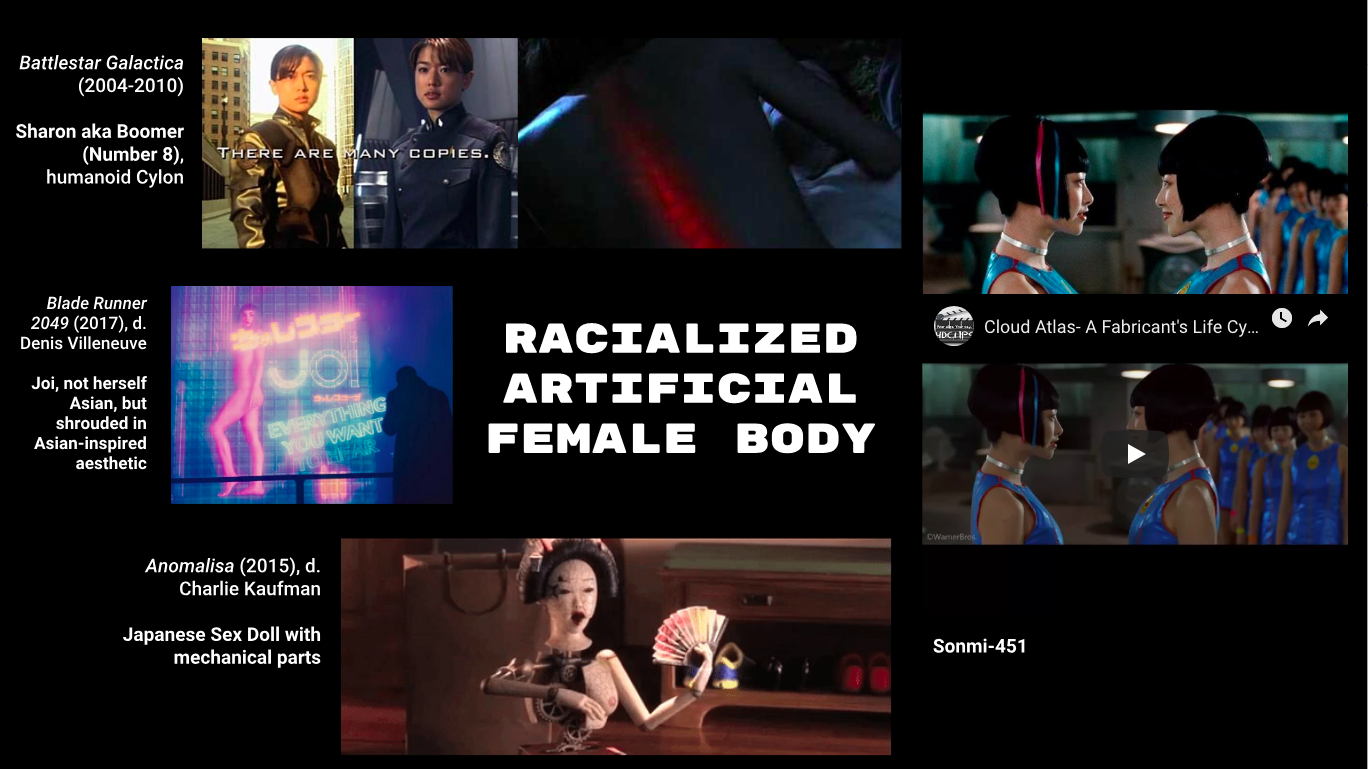

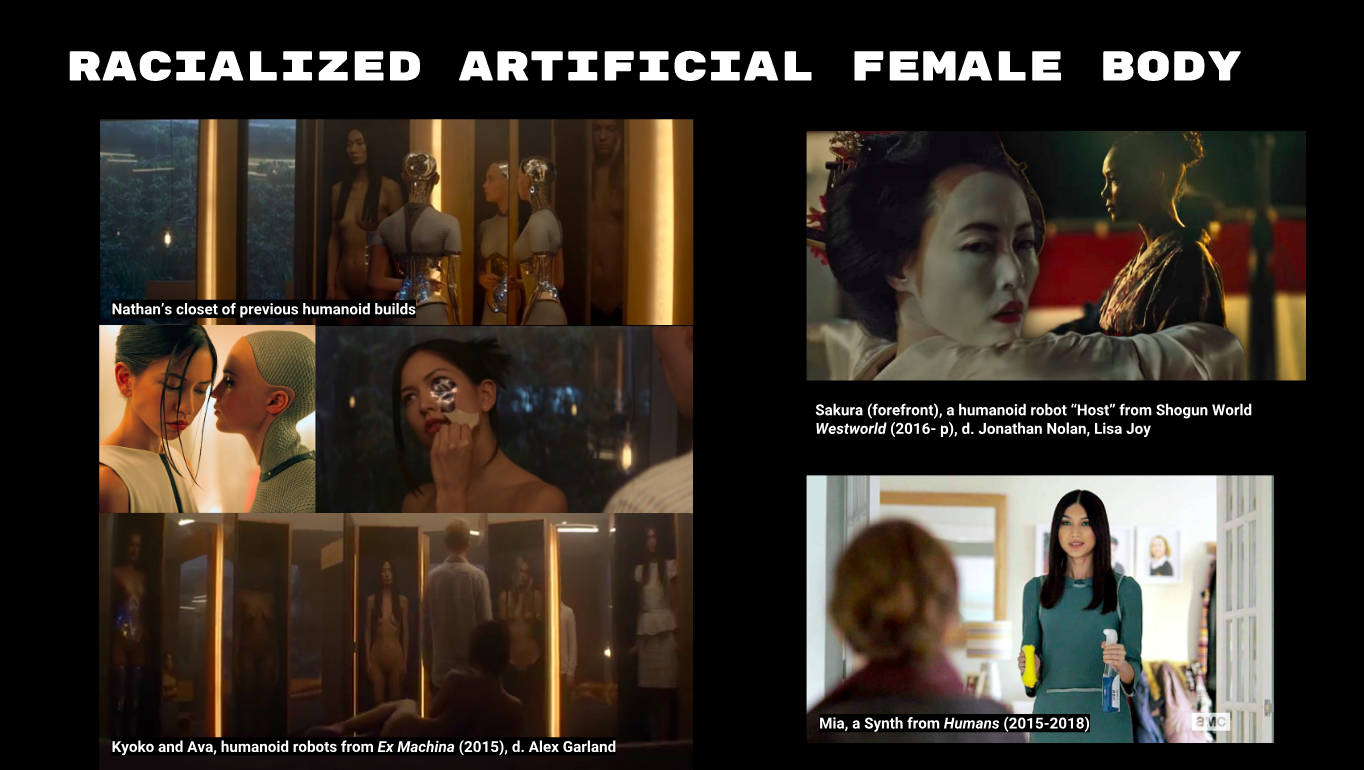

The world of science fiction is in many ways limitless. The genre itself suggests futurity, innovation, and an imagining of a world beyond the one in which we live. Yet, speculative fiction seems to rely on the continuous repetition of several tropes, especially when it comes to envisioning racialized and gendered bodies in the future. This is particularly true of speculative fiction productions created and released from the late 1990s to the 2010s. This period of time, as I illustrate through my dossier, churns out many iterations of the artificial female body, whether in a cyborg/humanoid form or as disembodied voices/technologies. Most interestingly, many of these artificial female bodies are racialized as Asians. From sci-fi thriller Ex Machina’s Kyoko to Cloud Atlas’ Sonmi-451, the artificial Asian female body is represented as an object of desire, a docile servant, a clone, a hypermodern geisha, and so on. She/it also tends to fulfill the following roles: 1) domestic helper 2) sex slave/prostitute 3) villainous seductress/insurgent in rebellion.

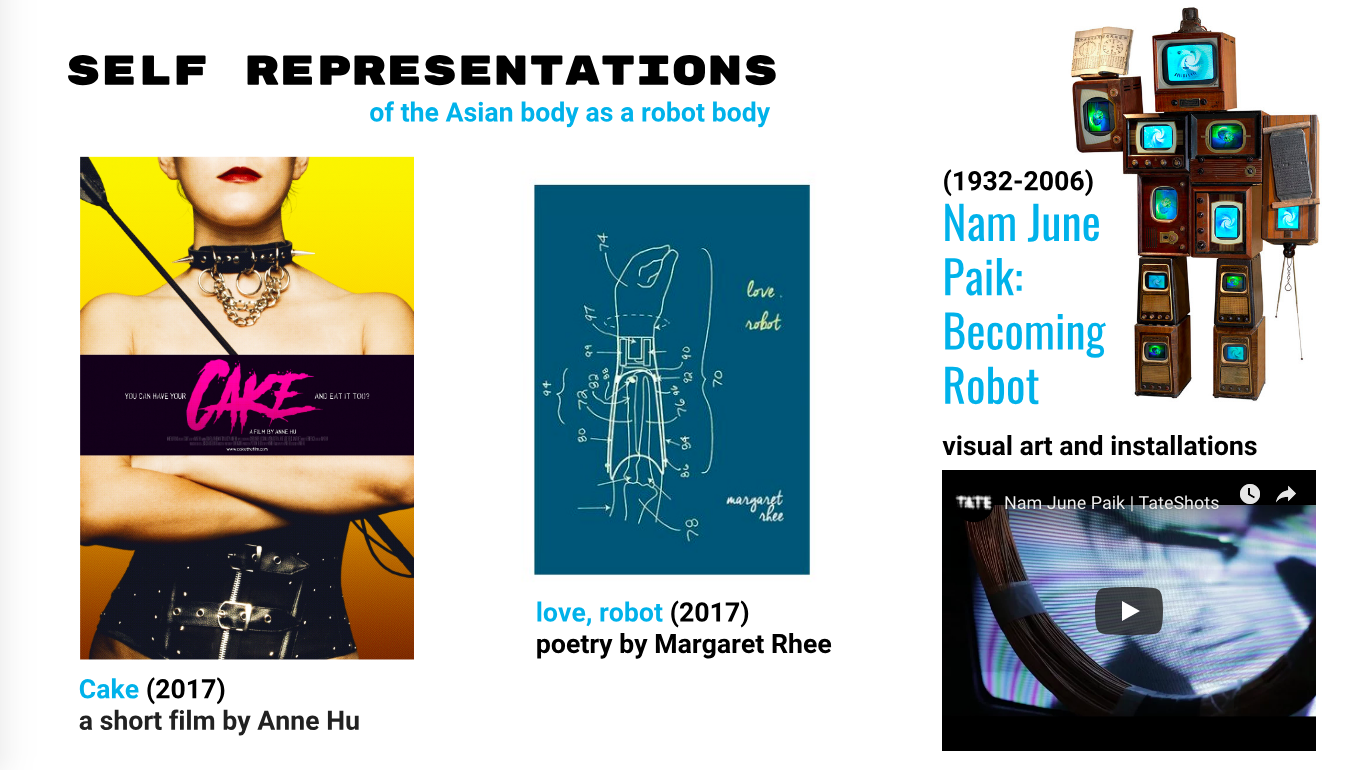

My project attempts to examine the archetype of the artificial Asian female body and how this body is gendered and racialized, primarily in sci-fi/dystopian films and television shows. Additionally, I draw a connection between imagined artificial female bodies in speculative fiction and gendered technologies (sex dolls, digital home assistants) in real life. I also trace the ways in which the artificial Asian female body is a continuation of the hypersexual “fembot.” Using the frameworks of Orientalism/techno-Orientalism alongside feminist film theory, I analyze the ways in which the artificial Asian female body makes visible masculine mastery and control over technology and the female body, as well as the process of constituting a fetishized and eroticized “Other.” The artificial Asian female body embodies both the Asian American history of exclusion/alienation and contemporary anxieties about the foreign, robot-like Asian body in the current age of global capitalism. Finally, I try to uncover what it would mean for Asian/Asian American artists/writers/filmmakers to reckon with these representations of the Asian body as robot body in projects of cultural production.

Link to Paper: Final paper

Anne Hu’s Cake (2017): A possible method of responding to the hypersexualized artificial Asian female

Annotated Bibliography:

Haraway, Donna J. “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Manifestly Haraway, University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Haraway’s text looks toward a feminist posthumanism in its discussion of science, technology, and feminism in the twentieth century. Haraway rejects the rigidity of binaries and instead proposes a hybridized, ambiguous model of the cyborg as a means of restructuring identity. This text will be foundational to my critique of modern-day gendered technologies and my analyses of how gender and sexuality relate to the archetype of the artificial Asian female.

Morley, David, and Kevin Robins. Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries. London: Routledge, 1995.

Morley and Robins’ book specifically addresses the way in which the formation and transmission of media shape cultural identities in the contemporary age of rapid globalization. The chapter “Techno-Orientalism: Japan Panic” explicates the tensions and anxieties that the West harbors in relation to the Far East and treats Orientalism as a conceptual framework in the context of countries moving rapidly toward modernity.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen, Volume 16, Issue 3, 1 October 1975, Pages 6–18

Mulvey’s text is useful in supporting/nuancing my interpretation of the artificial female body and the racialized artificial female body. Mulvey’s text serves as a theoretical lens through which to examine the embodiment of masculine desire and pleasure through the construction of the artificial female body. I use Mulvey’s framework of the male gaze in conjunction with the emergence of the “white gaze” to which the artificial Asian body is also subjected to.

Roh, David S., Betsy Huang, and Greta A. Niu. Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia In Speculative Fiction, History, and Media.

This text lays out the different ways in which Asia and Asians are depicted as hypermodern and hypertechnological in various forms of media, with special emphasis on speculative fictions. I will mostly refer to the chapter, “Technologizing Orientalism” in order to define techno-orientalism and form the theoretical groundwork on which to build my analysis of the artificial Asian female body.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. 1st Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

Said’s Orientalism is fundamental to my project as the text explicates the concept of orientalism, underscoring the perceived dichotomy between the inferior (and homogenous) East and the superior West. Said’s work is canonical to many scholars studying imperialism, racism, and power. This text serves as the theoretical basis of my analysis of the artificial Asian female as exoticized and fetishized “other.” It is also the text that the theory of techno-orientalism draws upon.

Stam, Robert ., and Spence, Louise. “Colonialism, Racism and Representation,” Screen, Volume 24, Issue 2, 1 March 1983, Pages 2–20

Stam and Spence examines “filmic colonialism and racism” as a means of deconstructing racist visual representations. This text uses a textual and intertextual approach to analyze Western cinema’s treatment of “otherness.” I rely mostly on the section, “Imperialism and the Cinema” to contextualize the relationship between the archetype of the artificial Asian female body and the apparatus of power.