United in Anger: A History of ACT UP can be views as the same coin upon which the two sides of Notes of a Signifyin Snap! Queen by Marlon Riggs and Forgetting ACT UP by Alex Juhasz lie. One tells the story of a gay black man’s journey through life and into academia and journalism, only to be rejected by a societal brotherhood that he’s realized only wishes for his to conform or die, while Juhasz’s work shows a similarly somber view of the act of archival of ACT UP and the remembrance of ACT UP itself. At the center of both can lie this documentary of what happened in the span of time covered in the film’s lens.

Riggs’s piece gives a histrical-biographical account of the 90s and living as a black gay man. As he recalls the experience of entering Harvard, studying history, then going on to realize journalism, and seeing around him black men, gay men, but no black gay men to speak of. This develops his sense of alienation from the culture of Harvard, having to don a mask of the “Silent Black Macho” to get by as what he can pass as by his appearance alone: a “hidden” intellectual, within a black body, using this stereotype as a defense to not be branded as something worse than what is already labeled in his skin.

Riggs’s experiences of academia was further alienated as he pursued journalism, hoping to study “the evolution of the depiction of male homosexuality in American fiction and poetry”, but was told at every turn by professors that they were “not experts” in the subject, and therefore did not want to touch it. He could only find a graduate student willing to work with him in his interests, and thus realized that there were levels of “allowance” in academia to which you could go against the grain of academic conformism, and he was too far out at the margins, for those with academic power to want to touch his intellectual curiosities. This discovery, or rather rediscovery of the brotherhood of academia that is a brotherhood of whiteness that he saw anyway mirrors the work of ACT UP, such that the bureaucratic levels of the FDA, CDC, and the federal government generally had levels of “allowance” to what they could pay attention, and dying gay people were too far outside of the brotherhood of business as usual, so suddenly everyone tasked (as were their jobs) with treating the AIDS epidemic were “not experts”, where the people at teh center of the issues had to become the experts.

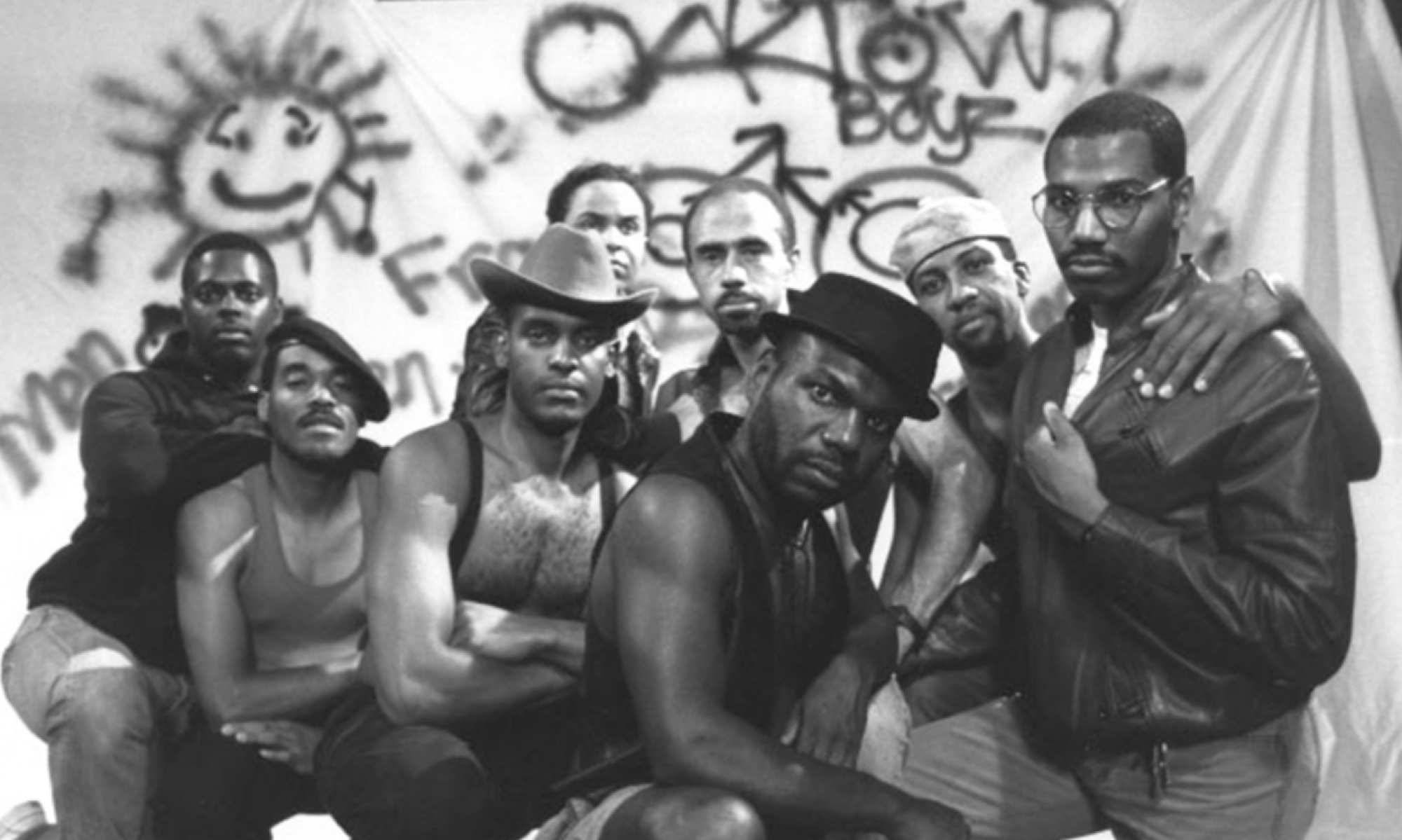

Juhasz’s piece on the remembrance and misremembrance of ACT UP serves as a similar discovery of the actions of the white brotherhood intelligentsia, in the opposite direction in time; where Riggs’ experiences illuminate the actions of the brotherhood to preserve the past, Juhasz’ work illuminates the work of the brotherhood to maintain a hold on the future. In Forgetting ACT UP, Juhasz illuminates the perspectives of ACT UP (mostly in the sense of their past actions) and shows that many representations of ACT UP not only forget the more grassroots level work by activists (the smaller actions like community education), but also forget the actions of people of color within the movement. This collective lack of archival of the work of activists of color is of course heavily coupled to the fact that grassroots actions were heavily carried out by people of color, whereas the “sexier” (=whiter) actions of protest and ACTing UP were far more representative of white activists. Juhasz even from the beginning shares a perspective that veteran activists often did not recognize the majority of people at ACT UP meetings when the movement gained heavy traction. The exciting, emotional work was very often done by white, educated, gay activists, whereas the more grassroots, dangerous, possibly even less consequential work was done by people of color, and was thus forgotten in the eyes of documentaries like United in Anger, where most of the representation of activism was activism in the form of these more heated, controversial demonstrations, rather than smaller actions of education or civil disobedience. In the wake of the upheaval of the makeup of activism, fewer veterans appeared at ACT UP meetings, and the movement a the superficial, but most visible level was overwhelmingly privileged.