An Infra-Normal Encounter

The initial idea we had for this exhibition was to create a sound archive of the lives of the books located at Princeton’s Firestone Library. Through the audio-recordings of the popular and less frequently visited parts of the library; rush hours and after hours; the moments of opening and closing we hoped to trace divergent forms of human contact with the books and the books’ lives of their own in their mere presence. As we thought through, we imagined juxtaposing this sound archive with some video recordings: by applying the sound of the empty library at night to the video recordings of peak hours; the chatters during the bag searches at the exit to the ID checks at the turnstiles; the initial opening of the gates of library in the morning by the staff to the removal of the waste of the day from the premises; the rush at the lobby and around the printers to the quiet study rooms -and vice versa- we wanted to reverse the auditory and visual experience of being with and around the books.

None of these recordings were possible to make, as the library space turned out to be inaccessible for such an endeavor. Nor was the exhibition hall that we wanted to display the recordings accessible to social gatherings due to recent Covid-19 restrictions.

As we started looking for alternatives, our initial interest in approaching [de]accession through the quotidian experience remained with us. In the sound of the books dropping, doors opening and closing, coffees spitting, we were looking for habits, gestures, instances that we tend to overlook in our thinking about the library as a rather ritualistic space and/or as the sanctuary of knowledge production and circulation. Listening to the quiet spaces and moments of the library, too, we were seeking to find the “lower frequencies” of such quotidian experiences (Campt, 2017: 7). In both, we were, in a way, interested in uncovering, in the words of Georges Perec (1997), the infra-ordinary— “what seems to have ceased forever to astonish us” (206).

Just like the infrastructures -the presence of which attract our attention mostly through their failure-, Perec stresses, we tend to live in the habitual without questioning it until it culminates into an issue, the spectacular, the event. Attending to the habitual, according to him, involves not simply stressing the ordinary at the expense of the extraordinary or the banal as opposed to the exotic, but also questioning the conditions of significance, the conditions of knowing that separate them.

“Describe your street. Describe another street. Compare.

Make an inventory of your pockets, of your bag.

Ask yourself about the provenance, the use, what will become of each of the objects you take out.

Question your tea spoons.

What is there under your wallpaper?

How many movements does it take to dial a phone number? Why?

Why don’t you find cigarettes in grocery stores? Why not?

It matters little to me that these questions should be fragmentary, barely indicative of a method, at most of a project. It matters a lot to me that they should seem trivial and futile: that’s exactly what makes them just as essential, if not more so, as all the questions by which we’ve tried in vain to lay hold on our truth.”

With Perec’s invitation to the endotic in mind, we landed on the idea of approaching the quotidian experiences of human contact with the books and the books’ lives of their own by making an inventory of the checkout cards attached to the back covers of the books. Starting with the “extraordinaries” of our respective disciplines (classics and anthropology), we traced the lives of the books sitting right next to them. We in a way, talked to the checkout cards to foreground what is repeatedly overlooked; to highlight the books that do not have human contact beyond the coincidental encounters due to their placement right next to the “canons;” to speculate about the conditions of accession and deaccession; to think about the politics of knowledge production and circulation.

The website of the Firestone Library states that the library does not deaccession books. Furthermore, it adds, even though it is not the largest university library in the world it is leading in terms of books accessible to per student enrolled. A selective inventory of the checkout cards helps those books in accession yet discarded access circulation they have long been denied. Likewise, it complicates the library’s claim to deaccession revealing multiple, crisscrossing paths of [de]accession.

PART 1: an annotated bibliography of those who were never “accessed”

Figs. 1, 2:

Figs. 1, 2:

Checkout cards for two copies of Scipio’s Dream.

The pictures above show different copies of the same book: English translations of Scipio’s dream, a famous passage from Cicero’s De re publica (figs. 1, 2). It’s the sort of book that doesn’t get much use anymore: though it may have been of use as a school-text or as a translation aid for Latin students, most modern readers interested in Cicero’s De re publica would look for an updated edition. In that sense, neither of these books is quite as alive as other library texts: the last time one was checked out was 1999. However, there’s an important difference between the two copies, as well. Fig. 1 shows the copy which was furthest to the left –– i.e. the first one you’d see on the shelf when looking for the book. Fig. 2 shows the other copy, sitting next to it. Based on the lack of a checkout card in the back of volume 2, it seems that the latter was never checked out in its life: without exception, every library patron who has made use of this edition has apparently used its neighbor.

Looking at the two books sitting next to each other on the shelf –– identical, dusty, beaten-up –– you wouldn’t know they have lived different lives. They look the same, they are the same, but only one of them has been checked out –– and neither has been in 23 years. They’re still there, of course: you could walk in and check them out any time. However, they seem to be moving through time in a different way than the volumes around them, some of which are constantly in motion. The fact that these books remain frozen on this shelf –– for now, at least –– reminds us that “circulation” means different things for different books.

Divergent trajectories of the two books sitting right next to each other suggest that the books’ access to human contact is not distributed equally, even when they are the same in content and form. While mere luck appears to be what distinguishes the lifespan of the 2837.392.411 version of Scipio’s Dream from its neighbor, other books are overlooked for reasons ranging from politics of citation to the relative “accessibility” of the language they are written in. For one thing, the actual content of a book seems to be far from determining the level of human touch it receives as the human interest seems to be contingent on many other factors that we do not necessarily think about as we navigate through the bookshelves.

One popular book that marks an “extra-ordinary” moment in the history of contemporary anthropology is Writing Culture: The Politics and Poetics of Ethnography (1986), edited by James Clifford and George E. Marcus. It marks an “extra-ordinary” moment in providing a novel critical perspective on the canons of the discipline and altering the ways in which ethnographic research and writing are imagined and practiced since the publication of the book. As the opening quotation by Roland Barthes also points at, the book has also been celebrated as a remarkable contribution to the interdisciplinary dialogue between anthropology and humanistic research.

. Fig. 3:

. Fig. 3:

First page of the introduction of Writing Culture.

Underlining the authors cited by Clifford in the introduction, one of the readers who borrowed the book from Firestone Library directs our attention to the books the first page invites us to contact, albeit indirectly. In response to the call issued by Clifford and this anonymous reader to consult these books, we visit their location in the library below. While doing so, we also pay a courtesy visit to their neighbors next door, in a manner foregrounding the stories told in the books that are shadowed by their neighbors high-in-demand.

But first, we start with visiting the shelf on which Writing Culture itself is located in order to “talk to” the checkout cards of the books sitting right next to it.

. Figs. 4, 5:

. Figs. 4, 5:

Writing Culture and its neighbors on the shelf and the Writing

Culture’s checkout card (with a mask behind, which happens to

be there).

Writing Culture sits in between When They Read What We Write that reflects on the reception of ethnographic works by those on whose stories and narratives the research expands, and Ethnos and Mythology: Elementary Structures of Ethnography published in Russian that studies disciplinary boundaries that separate anthropology from other disciplines while also reflecting on the relations between those researched and researching. Even though all share an interest in the politics of representation, the interest of the readers in the books is far from being distributed equally, with When They Read What We Write leaving the premises only twice and Ethnos and Mythology remaining within the library since its initial placement on the shelves.

. Figs. 6, 7:

. Figs. 6, 7:

The first page and the checkout card of When They Read What

We Write.

When They Read What We Write (1993) – Stimulated by discussions of ethics and responsibility in anthropological fieldwork, this collection of essays explores what happens when people who are the subjects of the research read or learn about what has been written about them. The most acute problems arise from biased media reports in newspapers and on television that misconstrue the findings of the anthropological study. This work shows how long-term relationships of trust and cooperation between subject and researcher can be irrevocably damaged by misinformation, rumor, or lack of forethought. The ten seasoned ethnographers writing with considerable hindsight warn of the dangers of ignoring the native readership and suggest strategies that will avoid misunderstandings and misrepresentations in the future.

Figs. 8, 9:

Figs. 8, 9:

The cover and the last page of Этнос и мифология (where the

checkout card is supposed to be– if filled).

Этнос и мифология: Элементарные структуры этнографии – Ethnos and Mythology: Elementary Structures of Ethnography (2009) – The book attempts to create a holistic image of ethnography (ethnology), discusses the problems of forming its disciplinary boundaries, the subject and object of research. In this context, it is proposed to solve some specific scientific problems related to research on folklore and kinship systems. The monograph is intended for students, teachers of humanities faculties, ethnographers (ethnologists) and specialists in the fields of related sciences.

Next, James Clifford and the anonymous reader direct our attention to Roland Barthes’ “Jeunes Chercheurs” in Le bruissement de la langue and to Elenore Smith Bowen’s Return to Laughter. The former is not available in the library; it is in circulation; on someone’s bookshelf, on their desk. But the neighbors are waiting: Estética de la creación verbale by Bachtin and Erudizione e leggerezza. Saggi di filologia comparativa by Paolo Cherchi.

. Fig. 10:

. Fig. 10:

The shelf of Le bruissement de la langue.

While its neighbor is currently gone, Esthétique de la création verbale seems to have its share of traveling outside the library a couple of times. Erudizione e leggerezza. Saggi di filologia comparativa, on the other hand, has been indoors for a long time, without anyone “checking-it-out” so far.

Figs. 11, 12:

Figs. 11, 12:

Front cover and the checkout card of Esthétique de la creatión

verbale.

Esthétique de la création verbale (1964) -Throughout the publications, the figure of Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975) appears as one of the most fascinating and enigmatic of European culture in the middle of the 20th century. We can indeed distinguish, like Tzvetan Todorov does in his presentation, several Bakhtins: after the critic of the reigning formalism, the Bakhtin phenomenologist, author of a very first book on the relationship between the author and his hero; the sociologist and Marxist Bakhtin of the late 1920s, who appears in Dostoyevsky’s complex Problems of Poetics; the Bakhtin of the thirties, marked by Rabelais and the great cultural explorations in the field of popular festivals, carnival, the history of laughter; the “synthetic” Bakhtin of the last writings, not to mention many other possible ones. The texts selected here come from three important moments in this rich career and shed light on them.

The works collected in this book offer a picture of Bakhtine’s thought in an arc that extends from 1920 to 1970 and represent a finished sample of his style. With an unusual critical sensitivity, he warned that in every word there are echoes of other people’s voices and that discovering that game of affinities and dialogical tensions between the self and the other is the way to understand both a trivial conversation and the complex construction of a novel. Author of key texts to think about social discourses, Bakhtin never makes the literary work the final goal of his considerations but the starting point to clarify issues that transcend it: in the thickness of language, he tells us, ideological assessments and antagonisms can be read; but, above all, the position that each subject is willing to assume in relation to others and to the world.

Figs 13, 14:

Figs 13, 14:

Front cover and the checkout card of Erudizione e leggerezza.

Saggi di filologia comparativa.

Erudizione e leggerezza: Saggi di filologia comparativa – Erudition and Lightness. Essays on Comparative Philology- (2012) –The essays gathered together in this volume offer a sample from the broad expanse of Paolo Cherchi’s scholarship ranging over classical and contemporary times, Italian and Hispanic studies, examining the cultural realities of Europe and America, and moving between the languages of Latin and English. Avoiding the trap of reducing literary criticism to solely philological considerations, while nevertheless respecting the field when it has something new to say, the author has always kept his distance from literary theory, trusting instead the profound and rare insight that allows him to roam freely with lightness and humor through the various fields of the humanities. The thread that ties these essays together is woven from the sheer variety of Cherchi’s interests, and constitutes an attempt to encapsulate his particular mode of combining philology and erudite comparative methodology that is at once unique and immensely valuable.

Next, we are directed to Return to Laughter, which, as it turns out, could not claim a space in the library stacks but is located in ReCAP, the library’s main off-campus storage facility: this choice was probably made by the relevant subject librarian, for unknowable reasons. Hence we move on and following the citations of books marked on the first page of Clifford’s introduction, we pay a visit to Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa and its neighbors.

Figs. 15, 16:

Figs. 15, 16:

Coming of Age in Samoa on the shelf and the checkout card

attached to it.

While Coming of Age in Samoa is in high demand, its neighbor to the left, Mutiny and Romance in the South Seas by Sven Wahlroos, also seems to have its share of traveling in and outside the library a couple of times. As the description of the book also attests, the spectacularity of the event that the book reflects on may be among the reasons that attracted visitors. Coming of Age in Samoa’s neighbor to the left, Samoa: Pacific Pride by Graeme Lay (despite a shared geographical focus), on the other hand, has left the library only twice.

Figs. 17, 18:

Figs. 17, 18:

The first and last pages of Mutiny and Romance in the South

Seas.

Mutiny and Romance in the South Seas (1989) – Who has not heard of the mutiny on the Bounty? For two hundred years this event has fired the imagination of millions of people, countless books have been written on it, and five motion pictures—so far—dramatized it on the screen.This book is unique in the literature on the mutiny and is the first companion volume to the story. The first part, the Bounty Chronicle, gives a panoramic, yet detailed, month-by-month account of the events, starting before the Bounty’s departure and ending with Fletcher Christian’s death on Pitcairn Island. It even chronicles Captain Bligh’s second breadfruit expedition of which so many people are unaware. The second part of the book, the Bounty Encyclopedia, is full of all the exciting and fascinating details surrounding this great story.

Figs. 19, 20:

Figs. 19, 20:

The cover and the checkout card of Samoa: Pacific Pride.

Samoa: Pacific Pride (2000) – The book introduces the Samoa islands – their geography, the history of the people and their way of life today. It reveals a proud society based on ancient traditions which has withstood the impact of colonization – embraced many modern ways – yet retained a unique lifestyle centered around the family and village.

. Fig. 21:

. Fig. 21:

The shelf of checked-out Argonauts of the Western Pacific and

its neighbors.

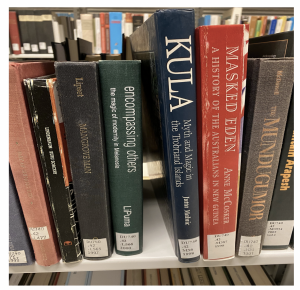

Last, following the citations underlined on the first page of Writing Culture, we pay a visit to Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific, who is not at home. Its neighbors, Encompassing Others: The Magic of Modernity in Melanesia by Edward LiPuma and Kula: Myth and Magic in the Trobriand Islands by Jutta Malnic, though, are there waiting for visitors. The books seem to be located next to each other with respect to their shared geographical interest. Similarly, they complement each other in being either ethnographic and/or insider accounts of daily life. Notwithstanding these shared qualities, they hardly attract similar amounts of attention sitting right next to each other in the library. Likewise, even though these books neighboring each other (like the ones above) are actually in conversation by their topic, methodology, or even by direct citation, they hardly enter scholarly conversation in similar terms to each other. What we try to do with this annotated bibliography is to take this space to call attention, first and foremost, to their presence and to the contributions they make to the discussions that have long defined our disciplines (as well as the boundaries among them and challenges to these boundaries).

Figs. 22, 23:

Figs. 22, 23:

The first and last pages of Encompassing Others.

Encompassing Others: The Magic of Modernity in Melanesia (2000) – An engaging, beautifully written account by an ethnographer who lived in the mountains of Papua New Guinea, Encompassing Others is at once a history of the encounter of two cultures and an attempt to challenge theoretically the main concepts that have informed the study of modernity. Going beyond accounts that grasp modernity solely in terms of domination, imperialism, and local resistance, it explores how capitalism, Christianity, and mass commercial culture enchant the senses, create a carnival of new goods, and open up new possibilities for thought and action.Focusing on the Maring people of Highland New Guinea and on the Westerners who interacted with them, Edward LiPuma presents issues from the perspectives of both sides. We hear the voice of the Anglican priest from San Francisco as well as the most powerful Maring shamans. Further, the book seeks to develop a theory of generations that helps explain how change accelerates and societies take on new directions across generations.Theoretical, descriptive, but almost entirely free of jargon, this book is intended for all those who are interested in how the West’s encompassment of other peoples influences how these others conceive of their past, imagine their future, and experience the present. It will have wide appeal for anthropologists and others concerned with colonialism, globalization, and the formation of the nation-state.

Figs. 24, 25:

Figs. 24, 25:

The cover and the empty checkout card of Kula.

Kula: Myth and Magic in the Trobriand Islands (1998) – Many times the Trobriand Islanders have been studied and written about, but never before has their story been told this way, from the inside, through the voices of understanding and belonging. Never before has such a wealth of superlative photography presented the life of the Kula Ring, with all its joyful lessons, a rich heritage of practices for survival.

PART 2: accessing deaccession

Firestone Library seems like a counterintuitive place to think about deaccession. After all, the library never actually deaccessions books –– they accumulate, and circulate, without end. This is, in some ways, a nice thought: unlike living things, the books in this library never decay, never get old, never die. Our regular engagement with them as library patrons means some small participation in something meant to continue long after we’re gone.

But although Firestone, like many institutions, might project immortality, things get more complicated beneath the surface. When you look closer at a given shelf, it becomes clear that these books aren’t just small components of the enormous unity of the library’s catalog: in fact, there are lots of smaller lifecycles ticking away, each with its own peculiar rhythm.

The books in Firestone follow the Dewey decimal system, organized by subject and author. However, in a library which never takes books out of circulation, this can result in some strange juxtapositions. Princeton selects the most fragile books for preservation as rare volumes; however, given the enormous size of the collection, this means that books in the stacks can still be two hundred years old, or older.

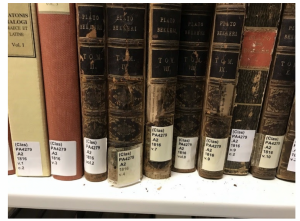

. Fig. 26:

. Fig. 26:

The complete works of Plato.

This set of collected works of Plato sits on the shelves next to monographs published within the past several years, constructing an apparent equivalence between extremely heterogeneous volumes (fig. 26). Some volumes in this set have become hard to open without risking cracks to the spine; as you can see in the picture, small pieces of two-hundred-year-old binding are scattered across the shelf.

. Fig. 27:

. Fig. 27:

Works of Tacitus, vol. 1.

The above volume of Tacitus is part of a four-volume set from 1831, the spines now barely legible (fig. 27). They sit on the shelves next to up-to-date commentaries produced within the last two decades, as if united in purpose and aim (fig. 28).

. Fig. 28:

. Fig. 28:

The complete set.

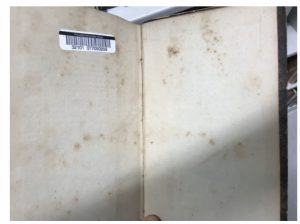

There’s a strange effect in seeing an up-to-date bar code on the spotted old paper (fig. 29):

. Fig. 29:

. Fig. 29:

The lonely barcode.

Sitting in the stacks, old books like this look a bit caught off guard: like they’re part of a world they didn’t foresee, and which they don’t quite know how to navigate. Despite incidental damages, they’re well taken care of here; however, almost none of them has been checked out in decades. Tagged and cataloged, they sit somewhat uneasily in the company of the living.

When you start to notice these points of discontinuity, it quickly becomes clear that there’s more heterogeneity than meets the eye in the clean continuity of the stacks. Many volumes in the Classics section, especially the older ones, were gifts or bequests to the library, originating from elsewhere. The Tacitus volumes shown above were part of the library of The College of New Jersey –– Princeton’s name before 1896 (fig. 30). However, they had another owner before the College, indicated by the ex libris stamp bearing the name of A. Trendelenburg. It’s hard to say much about their last owner, but since this last name isn’t very common, it’s tempting to assign the books to the family of Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg –– a German philosopher and classicist active in the 19th century. The English-language cursive at the bottom (perhaps written by an anxious student) lists emperors whose characters are described in the volume in question; the note at the bottom references the work of Theodor Mommsen, the 19th century historian of Rome. It’s hard to fill in the blank spots in this volume’s long history. However, it’s clear that it was extensively used, and prized, for a long time before it found its way to the bottom of an inconspicuous shelf in Firestone library. It, too, remains in circulation –– just as alive as any of the books next to it. However, it lives a very different kind of life.

. Fig. 30:

. Fig. 30:

Bookplate of the College of New Jersey.

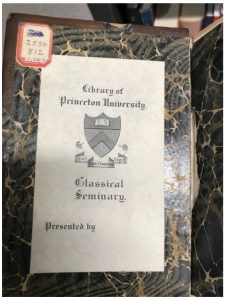

Further digging reveals quite a few volumes that came from elsewhere: the now defunct library of the Princeton Classical Seminary, for example, which used at least two kinds of bookplates over the years (figs. 31, 32):

Fig. 31:

Fig. 31:

Bookplate of the Princeton Classical Seminary.

. Fig. 32:

. Fig. 32:

Bookplate of the Princeton Classical Seminary.

All of this amounts to give the impression of a library of other libraries: the enormity of Firestone’s collection is constituted, in no small part, by the remnants of many smaller, deaccessioned collections, both private and institutional, which have found their way to its shelves. Firestone may never take books out of circulation, but in another sense, these books were deaccessioned long ago: they point back towards the dead names, dead collections, dead people which first marked them as their own. These small absences shed a different light on the immortality of eternal circulation.

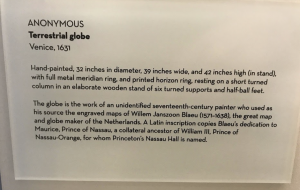

It may not be so easy, then, to characterize Firestone. It Is, of course, a circulating library: its utility is largely defined by its ability to put academic materials in its users’ hands. On the other hand, it is also something harder to categorize: an assorted collection of objects which point back towards other times and places, part museum, part archive, part curiosity cabinet. We are struck, in closing, by the sight of a 17th-century globe kept on the third floor (fig. 33):

. Fig. 33:

. Fig. 33:

17th century globe on the third floor of Firestone.

. Fig. 34:

. Fig. 34:

The information card for the globe.

As the sign (fig. 34) informs us, the globe was handmade for an ancestor of William III, Prince of Nassau-Orange –– the namesake of Nassau Hall. Its strange geographies, including its shaky, incorrect outline of North America, bear traces of colonial violence: at one time, this globe put the world into a Prince’s hands. Now, under a glass case on an empty patch of floor, it looks almost lonely: out of its job, mostly ignored by those who walk by it.

The possession of objects like this is part of what makes Firestone such an outstanding collection, with an astonishing ability to give continued life to the objects it contains. On the other hand, it also reminds us that Firestone is an archive of deaccessioned pasts: of objects away from home, marked by other times and other worlds. The project of eternal circulation is more complicated than it might seem.

CONCLUSION: the life of the library

There are, of course, many ways to check out a book. (And possibly many other ways to talk to the books discarded in the library.)

We are accustomed to act as library users: for most of us in the humanities, opening the online catalog and filling in a request has become a routine motion. We are less comfortable acting as library readers, in the full sense of the word: thinking not only about books, but also about the structures that determine their emplacement; seeing catalogued objects as participants in complex systems of being rather than windowless monads. Reading the library, in this sense, revealed these books’ implication in other times and other worlds, in bibliographies and libraries unfamiliar to us. As writers of dissertations which will, one day, take up space on a shelf somewhere and begin attracting dust of their own, this experience is a useful reminder that the things we read, like the things we write, tend to run away from us.

At the end of this encounter, we find that the promise of eternal circulation seems more complicated than it first appeared. These books’ circulation, the heartbeat which keeps the library alive, has always been arrhythmic and plural, determined by canonicity, empire, shelving, John Dewey, and many other vectors –– far from the steady thumping one hears with a stethoscope. This is what the infra-ordinary means, for us: an invitation to inhabit the space between the extraordinary and the banal, motion and stasis, circulation and deaccession.