Notes on the Dewey Decimal System

This virtual exhibit explores the deaccession of outdated language from the library catalogs in the Princeton University and beyond, the introduction of more contemporary and progressive language, and what remains after the wake of these changes finally settle. All catalog items listed in the Princeton University Library now feature a statement informing users of the deaccession of certain words from the library search in an attempt to list “materials in a manner that is respectful to the individuals and communities who create, use, and are represented in the collections,” and what to do if the users would like to deaccession another word or phrase from this listing. Instead of simply deaccessioning outdated language, library staff added new, more politically correct language, while leaving records of what was once there.

Notwithstanding the contemporary proliferation of attempts to “decolonize” the search terms, deaccessioning of the language used in cataloging is hardly a recent phenomenon. To the contrary, it has been part and parcel of the historical evolution of Dewey Decimal System (DDS), according to which around 200,000 libraries all around the world have long been categorizing and distributing books across library buildings and shelves. As the racist, sexist, and Western-centric foundations of the DDS are increasingly subjected to criticism, the decimal system witnessed rearrangement of a variety of categories and subcategories- with some of them being totally removed from the guidelines.

In this exhibit, we trace some critical accounts that stress inherent limitations of the DDS as well as changes made in it since its creation in 1876 by Melvil Dewey– himself denounced for racism, misogynism, and anti-Semitism. Providing a brief account of the alternatives to the DDS- such as the Library of Congress system, we trace how the Princeton Library has historically attempted to circumvent the limitations of conventional cataloging systems. While online search engines available in many libraries today can help sidestep some inherent limitations of the conventional cataloging systems by allowing library patrons use their own search-categories, the challenges posed by potential use and circulation of offensive language are far from being overcome: Hence, the more contemporary statement and attempts of universities to deaccession harmful language. In this light, we examine the co-occurrence of deaccessioned words and their replacements in the library catalog. In so doing, we invite you to consider the blurry space between deaccession and disappearance. Does recording the history of deaccession compromise the act of deaccession itself?

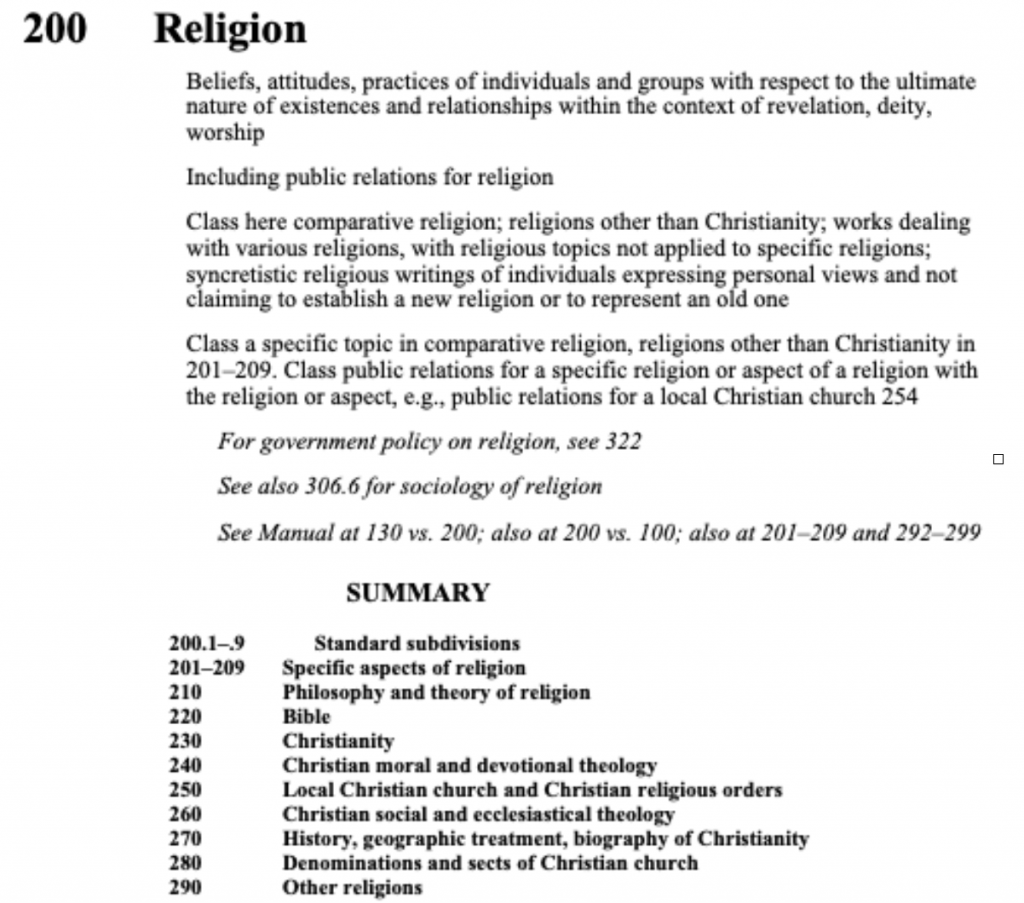

Dewey decimal system, which has long attracted criticism for its racist, sexist, and Western-centric underpinnings, is among the cataloging systems that are most commonly used by public libraries in the English-speaking world. A quick glance at its classification of religious as well as ethnic and national groups (figs. 1, 2) attest to these criticisms: While eight of nine subcategories of religion are designated explicitly or implicitly for Judeo-Christianity related subjects, all other religions are lumped into the subcategory of “other religions.”

Fig. 1: Subcategories of religion in DDS.

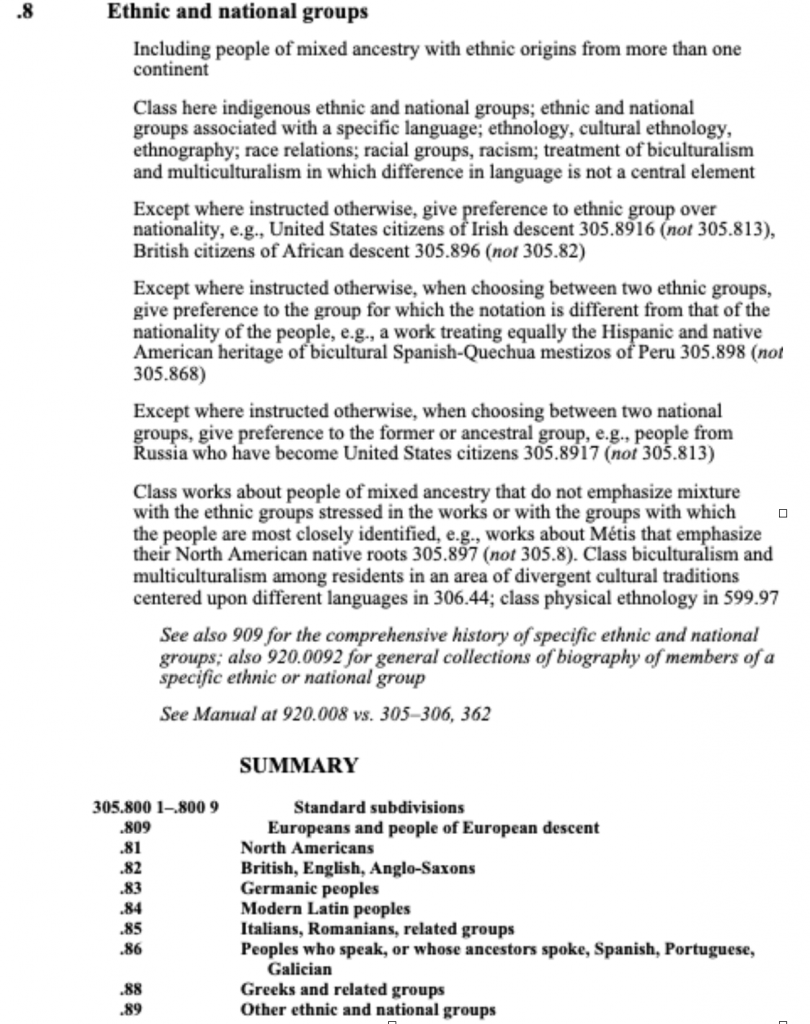

Similarly, whereas Western nationalities occupy eight distinct subcategories, world populations ranging from “people of African descent” to “East and southeast Asian peoples” are simply marked as “other ethnic and national groups.”

Fig. 2: Definition and subcategories of ethnic and national groups in DDS.

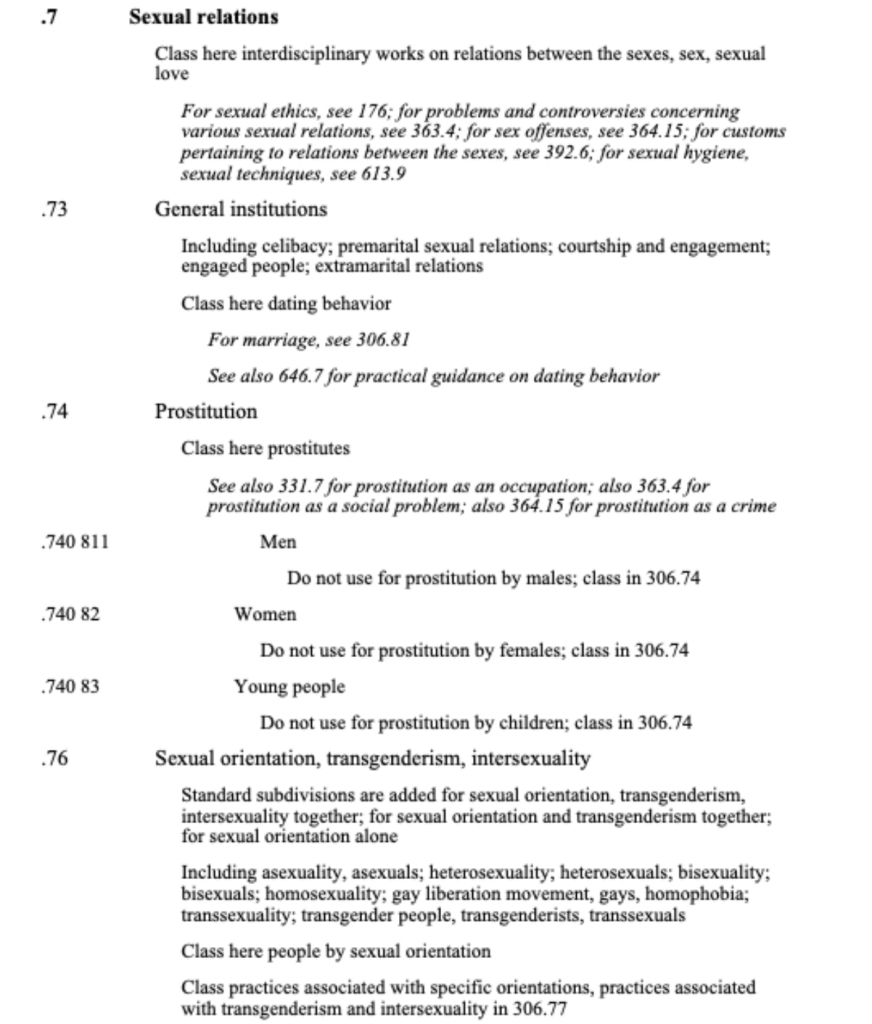

To the historians of science, such disproportionate representation comes as no surprise given the embeddedness of DDS’s origins in the late nineteenth century racial biases that marked the social science research. Nor does the (hetero)sexism of the original categorizations of Dewey System, on top of its inherent racism, catch the students of social sciences and humanities off-guard: While the original 1876 version of the system defined gender and sex only in binary terms, until 1932 there was no mention of homosexuality. Reflecting the hegemonic scientific discourse and sexual biases of the times, nevertheless, homosexuality entered the decimal system as a form of “mental derangement” and/or “abnormal psychology.” After an arduous journey in between the classifications of “neurological disorder” in 1965, “social problems and social services” in 1989, it finally landed in “sexual relations.” The most recent version of the system lists transsexuality, intersexuality, asexuality and bisexuality with homosexuality within this category, together with the 2018 additions of gender nonconformity and queer identity.

Fig 3: Definition and subcategories of sexual relations in DDS.

All these historical shifts suggest that the terms and categories of the very system used in accessioning/deaccessioning books itself goes through [de]accession. Furthermore, a closer look at the [de]accession of categories used in accessioning books sheds light into shifting interplays between the systems of oppression and struggles of people relegated to the margins of society (and as a result, of the decimal system). Deaccessioning of categories in favor of more inclusive ones, on the other hand, occurs slowly, leaving, according to many, particularly the western-centrism and the racial bias of the DDS intact. As the critics stress, implications of such categorizations exceed reproducing discursive hierarchies but also are implicated in the material reproduction of them in and through the libraries. Informing the organization of books in the library space, they pave the way for marginalization of divergent experiences of oppressed communities and/or the neglect of the contributions of people of color. Attempts to “decolonize” the cataloging systems come in multiple forms ranging from implementing editorial policies to render DDS more inclusive to more radical challenges to it by librarians such as Dorothy Porter who reworked the Dewey System by classifying works by genre and author in order to highlight foundational roles played by black authors in all subject areas. Beyond such radical attempts to rework the DDS, one other largely used conventional cataloging system is the Library of Congress Classification (LCC) system. While most academic libraries in the US now use the LCC, others are recently shifting from the DDS to the LLC, currently employing a combination of both (such as Northwestern University).

The problem in many “white libraries” using the DDC, explains Porter in her oral history, “every book, whether it was a book of poems by James Weldon Johnson, who everyone knew was a black poet, went under 325 [colonization]. And that was stupid to me.”

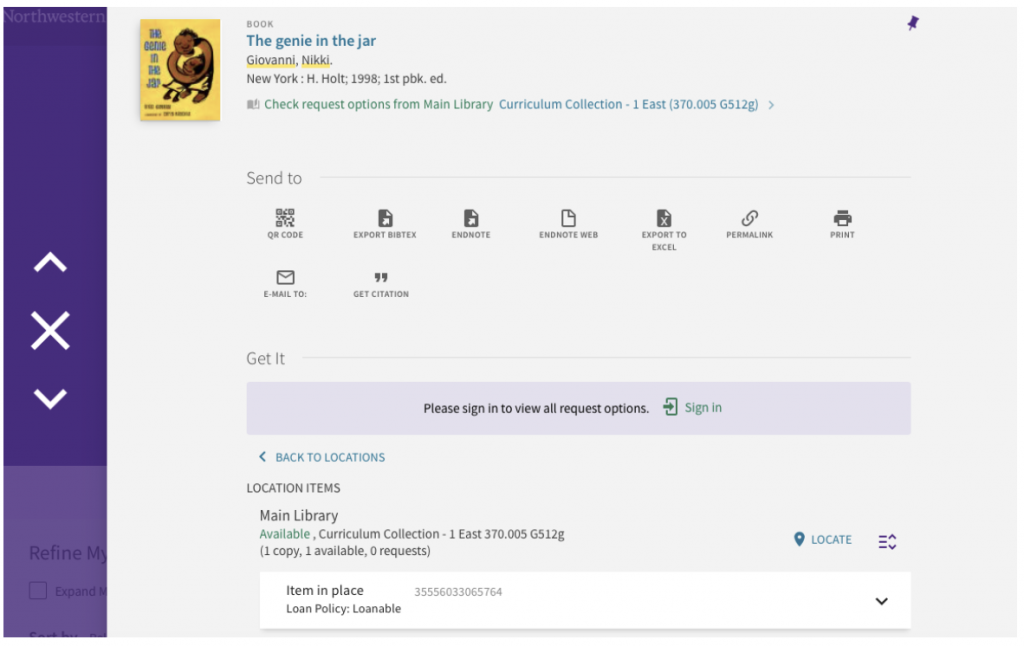

Echoing Porter’s recollections, The Genie in the Jar by Nikki Giovanni, for instance, appears under the broad category of “social sciences” in the DDS, separating it from other literary works.

Fig. 4: The call number of The Genie in the Jar, from the online search of Northwestern University Library.

This being said, a variety of other works by Johnson and Giovanni do appear under the subject category of literature in libraries using the DDS. It is possible to approach such (mis) categorizations as indicators of the multiplicity of the subject categories these literary works correspond to. On the other hand, there is something jarring in such works’ lack of acknowledgement as literary works as such but as “objects” of knowledge of social sciences in the way they are cataloged. Such form of a categorization corresponds to, as Fadi Bardawil (2020) aptly observes, hegemonic formulations of the West as the active site of production of abstract theory of social sciences in contrast to a “non-West” perceived as a mere locus of concrete facts where the social scientific theory is to be applied. (Or for that matter, the white subject as the producer of abstract and slicky thinking to be applied to a concrete and “messy field of research” that can be addressed through the literary accounts of the people of color.) In other words, on top of underestimating the literary contribution of these works, such form of a categorization renders them the “objects” of analysis, belittling the creative tensions and contributions inherent in them.

Another, possibly more plausible, explanation for such forms of categorization is historical: They may be the legacy of the hegemonic perspectives that mark the time when these literary works have first been cataloged by the librarians. Then the question is whether we need a radical reorganization of all the entries: What is to be gained or lost with such an attempt? How can a cataloging system stay tuned to shifting political understandings? In this light, we invite you to search your favorite writers in the library catalogs and contrast the way they are categorized in line with the DDS to the categories you actually associate their work with. What, do you think, is the right way to catalog them?

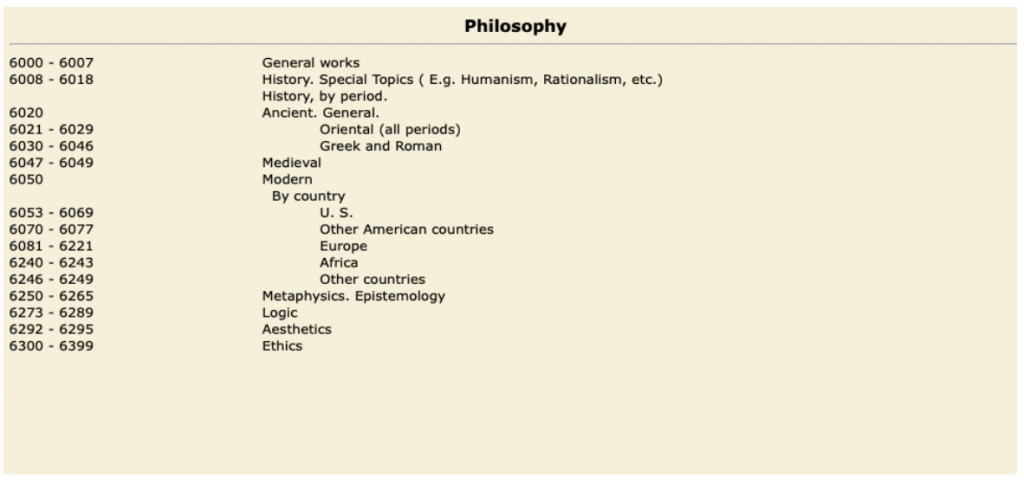

Princeton Library, on the other hand, has a unique history in the ways it [de]accessions search categories: different than many libraries that departed from the DSS in favor of the LCC, it had its own Richardson Classification System that was devised by Ernest Cushing Richardson, a University librarian. The system, which according to the library webpage was employed in response to the “inappropriateness” of the DDS, appears to be more egalitarian in the ways it distributed contributions of different populations and cultures to a certain subject category- while it still seems to fall short of overcoming the Western-centricism.

Fig. 5: Subcategories of philosophy in Richardson classification system.

In addition to the alternatives such as the Richardson system, the recent shifts to the LLC, and the more radical reworkings of the DDS such as that of Dorothy Porter, keyword searches now accessible through computerized library engines, according to some, offer a way to circumvent racism and sexim inherent in DDS by allowing library users to select their own terms of research. A closer look, on the other hand, suggests that such searches and cataloging around keywords is far from political controversy, pointing, once again, to ongoing [de]accession of the terms of accession.

Hazal Hürman and Angelika Joseph