The final days of the Princeton in Leipzig program were some of the most chaotic I’ve experienced in a long time. Between slipping and twisting my knee, speaking broken German with paramedics, hydroplaning in an Uber, scrambling for a last-minute ICE train after my flight was cancelled, and then sprinting through the airport only to find the gate closed four minutes early due to an extended security screening—I’m not entirely sure how I made it home in one piece. These are not the memories I plan to hold onto, but they do underscore how unpredictable and disorienting travel (and life) can be, especially at the end of something so meaningful.

Looking back on the final recital, however, I’m filled with gratitude. I performed three pieces: the Allemande from Bach’s Third Suite, transcribed in G Major for double bass; a trio in C Major with Maurice on cello and Vito on viola; and The Art of the Fugue No. 5, alongside Charlotte on violin, Vito on viola, and Maurice again on cello. Each ensemble offered something distinct, but the trio in particular surprised me with how naturally the instruments blended. There was a warm, grounded texture to the sound that felt effortless and deeply rewarding to be part of.

The Allemande was, without question, the most personally challenging. Not because of the notes on the page — although Bach leaves no room for hesitation — but because solo playing still brings a kind of internal resistance I’m learning to overcome. Ensemble work comes more naturally to me; there’s safety and energy in collaboration. Playing alone is a different conversation. In preparation, I did everything I could to stay grounded: hydration, breathing exercises, walking, and even a slightly excessive number of bananas. I also tried pushups as a way to flush the nerves, but strangely it was effective.

The performance as a whole was deeply fulfilling. I particularly appreciated hearing the gamba sonata performed by James on bassoon. It inspired me to explore the piece myself, especially given the bass’s lineage in the viol family. It’s a reminder of how fluid and adaptable early music is — and how much more there is to explore.

The recital venue offered beautiful acoustics, which required restraint. I’m not often in spaces of that size, and learning how to let the sound breathe rather than over-project was a valuable lesson in itself. Performing Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring to close the evening was a perfect conclusion — a piece I’ve long loved, and one that felt amazing.

Our group came together the following evening for a celebratory dinner — a chance to unwind, reflect, and connect beyond the rehearsal room. We shared stories, laughed about our rehearsal blunders, and exchanged photos. It’s rare to feel so connected to a group in such a short amount of time, but this experience brought us together in a truly meaningful way. I leave with not just stronger musicianship, but with friendships I genuinely value.

This program has reaffirmed many things for me. That Bach’s music is inexhaustible in its beauty and challenge. I am grateful to the Princeton German Department, the music faculty, and every musician and mentor I encountered in Leipzig. And I hope to be back soon!

Author: Tendekai Mawokomatanda

Sunday, June 22nd — I finally heard Bach’s Mass in B Minor live, and I don’t think I’ll ever be the same.

I should start by saying I wasn’t emotionally prepared. I knew it was going to be breathtaking — it’s Bach — but I didn’t expect to be sitting there, score open on my iPad, feeling dizzy because the sound was coming from behind me. I had no idea the ensemble would be positioned that way, and trying to follow along while the music surrounded me in reverse stereo was… disorienting at first. But once I settled in, I was locked in. The acoustics were incredible, (I feel that 415 carries better than 440 or 442 and I don’t know why, it just resonates more) — every line rang out with this resonant clarity, and the voices cut through the space in a way that made it feel like the soloists were right beside me. I couldn’t believe how powerful and immediate the vocal projection was in such a huge space.

But what really moved me was the Sanctus.

I was teary-eyed. That movement already holds a strange place in my heart. The first time I ever heard the Sanctus was a few months ago, during the announcement of the new Pope on television. (For the record, I’m not Catholic — I just knew the chances of witnessing a papal election again in my lifetime were slim, especially since the current pope is relatively young. But I’m getting off topic.)

They (the Vatican ensemble) played the Sanctus during that moment — this overwhelming, cosmic-sounding chorus erupting as the new Pope stepped out onto the balcony. Even without context, that music hit something in me. And hearing it again now, live, with that same transcendent force — in a church, no less — was honestly too much. I was holding back tears while pretending to casually scroll through IMSLP so that Lucien or the older lady next to me wouldn’t see.

It was holy in a way that goes beyond religion. It felt like the heavens cracking open for a second. Bach somehow found the sound of awe itself and wrote it down.

That moment alone would’ve been worth the entire concert. But the truth is, the whole Mass was full of moments like that where time slowed, and where music spoke louder than language, where I remembered exactly why I love baroque music and Bach.

This past Saturday was one of the most meaningful days of my time in Leipzig so far. With Princeton, I had the opportunity to attend a performance of three Bach cantatas at St. Nikolai Church — the same church where Bach once served as music director. Even more surreal was the fact that the concert was conducted by Sir John Eliot Gardiner, someone I’ve admired deeply as a baroque conductor for years. Hearing his interpretation of Bach’s music in that historical setting was truly unforgettable.

After the concert, I had a conversation with the bassist from the orchestra, and what followed was something I never imagined would happen: she handed me her instrument and invited me to play it. It was an incredibly generous gesture — and one that meant the world to me.

What I didn’t realize at first was just how special that bass was. She told me it was 356 years old — even older than the average Stradivarius — and had been used to perform Bach’s cantatas and orchestral suites during his lifetime, when he was music director at St. Nikolai. It’s very likely that Bach not only saw this bass, but also heard it in the very works he composed. I was completely stunned.

At Princeton, I’m not even allowed to touch the original manuscript of BWV 33 — and yet here I was, unsupervised, holding and playing an instrument that once existed in Bach’s sound world. It was a moment that reminded me why I chose to study this music in the first place.

Later, I met Jenna, a violinist in the ensemble who also happens to be from the U.S., and coincidentally from the South, like me. Talking with her about life as a professional baroque musician was incredibly inspiring. She reminded me that pursuing a life in music — especially early music — is not only possible, but full of joy, curiosity, and community.

To end the evening, I had a slice of cake and an impromptu grammar lesson from Professor Rankin. His explanation of several German language points helped clarify things I had been struggling with all week. Learning German has not been easy, but I’m so grateful to have support from the Princeton German Department while I’m here — it makes all the difference.

I left the day feeling energized and thankful. So much so, in fact, that I decided to arrange a short excerpt from the third movement of Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 — just as a small way of reflecting on the joy I felt.

copy_A2A668A7-FAB1-436E-9C32-EF74A9AB1739

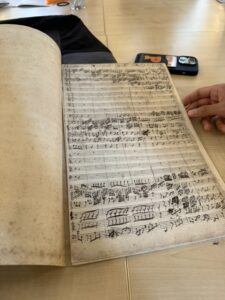

I think everyone could tell how blown away I was after our seminar with Professor Wollny—I really enjoyed it. One thing that made my heart burst was realizing that I had actually played BWV 33 “Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ” on continuo (bass) with Vito on baroque viola and the Early Music Princeton choir. I was truly amazed. But what really caught me off guard was learning that Bach originally wrote it in G minor, not A minor like it’s commonly performed today. Seeing the copies with all of his edits, scribbles, and crossed-out endings made me realize just how hands-on and experimental Bach was. It makes me wonder what the piece would have sounded like if he had kept some of those first ideas.

After finishing the first week of readings, and especially hearing Professor Wollny talk about Bach’s personality, I started to rethink the image I had of him. I used to think of Bach as really serious and almost untouchable. But now I see him as someone who could be funny, playful, and even a little rebellious. That came through both in his music and his life. Marshall explains in Young Man Bach, Bach had a temper, stood up to his bosses, and even once got into a sword fight with a student. He was also an orphan by age 10, which might have made him guarded and fiercely independent. It’s like he was constantly pushing against limits.

I’m not sure if the Bach that’s presented in Leipzig today—through statues, concerts, and museums—is always the full picture. Heller writes in Music in the Baroque, Bach’s image has been shaped over time by nationalism and tradition. We get the “great master” version of Bach, but not always the everyday, cheeky guy who made jokes in his Coffee Cantata or experimented with different keys. It’s easy to market the genius, but harder to show the full, messy, human side. I’m glad this seminar is helping us explore all of that, it makes me love his music even more.

I left so inspired that I decided to sight read the chorale from Bach du Großer Schmerzensmann on the bass. Doing this, I hope I can continue to adjust to this massive five string and help improve my intonation.

Hallo everyone! I saw Bach’s church and was AMAZED!! Thank you so much to Caitlin for this amazing photo outside the church

Danke,

Tendekai