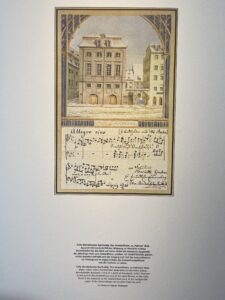

So that was it! The month finally came to an end and we performed our recital at the historic Alte Börse. I was able to perform two pieces (both by Schumanns) one was “Die stille Lotosblume” by Clara Schumann and the other was “Widmung” by Robert Schumann (which I learned a little bit later into the process than I care to admit translated to dedication).

The piece by Clara Schumann which translates to “the still lotus flower” is a very symbolic piece centering around of course a lotus flower and several other natural/organic potentially male actors. Apparently this structure was common in her pieces (especially in her art song where about one third of the compositions centered around flowers). I learned this funnily enough because of an article stemming from Princeton titled “Speech and Silence: Encountering Flowers in the Lieder of Clara Schumann” (you can find Dr. Heller in the footnotes!!) which talks about the imagery Clara utilized and its symbolism regarding gender when she discussed floral metaphors in her pieces. Namely the figures of the Moon which pours its golden rays into the bosom of the flower (somewhat reminiscent of impregnation) and the swan, which circles around the flower, gazing upon it, singing its song in which the swan wishes to fade away are the primary “male” influences according to the background the article provides. Their difference in roles (the Moon having such a profound, direct effect on the flower while the swan helplessly swims around it, its song almost fading away with it) provide an interesting juxtaposition to how Clara Schumann thought about men and their influence in a female figure’s life. In this specific piece (and apparently often in her lieder which focused on flowers, Clara would center whichever flower she chose and yet leave it un-impacted by the actions of “male” actors. What she truly meant by this choice is unclear and definitely up to interpretation.

Interestingly, I also learned from Christopher Parton’s article that Clara was gifted a flower book by Brahms, a common gift that women would use to share pressed flowers amongst each other (a sign of friendship). Some sources have said it was a subtle way for Schumann and Brahms to express their romantic interest in one another (perhaps with a pressed rose), but, similarly to Clara’s lieder, the flower book or “Blumenbuch” was definitely not a simple secret message carrier. Clara eventually filled it with flowers and titled it “Blumenbuch für Robert” and laid it upon her husband’s grave when he died.

Wow! I’ve given so much space to Clara, I may not have enough space for Robert! (Since that so rarely occurs the other way around, I think I’ll keep it this way). I think through translating and re-translating Widmung, I’ve re-interpreted it over and over again and still don’t know how to think about it. It’s such a strong dedication of love and affection but at the same time full of darkness, especially with the line “you are my grave” following sentiments like “you are my soul, you are my heart.” I honestly still have more thinking to do about how this piece really functions tonally. Is there a hint of desperation? Sickness? Or in its darkness does it really encapsulate the painful nature and backwardness of love?

TBD for now!

Gabrielle