Nearing the end of our trip, we took some time to explore Mendelssohn House before attending a Lieder recital with Columbia students. Since we only had an hour to get through the whole museum, we had to make our time count. The museum was structured into three floors: the first explored general contributions of Felix Mendelssohn tied into Leipzig history, the second featured more about his home life and his wife, Cécile, and the third focused on his sister, Fanny Hensel who was also a composer.

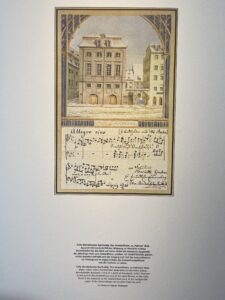

Before going to the Mendelssohn House, I listened to an two episodes of the podcast: Opera After Dark which gave some background on both the Mendelssohns. I really enjoy the podcast because it’s well-researched (one of the hosts also speaks on the Met Opera Guild podcast and is a musicologist) but the tone is lighthearted and silly which for opera works really well since so many opera plots are fairly insane to begin with. Going back to the Mendelssohns, the episode I listened to on Felix centered more on his personal life with topics ranging from his somewhat parasitic relationship with Fanny, attempted affair later in his marriage, and his unflattering neck beard. The museum offered a much more positive view of Felix. It detailed his contributions to Leipzig, most notably through the Gewandhaus. As one plaque described, Mendelssohn was, for a time, the Gewandhaus orchestra’s conductor whose “sense of moral responsibility impelled him to call for socially minded benefits for the members of his orchestra” which included working for the official recognition of the Gewandhaus as a municipal institution and increased salaries for his musicians. It was extremely exciting to hear some of his music as part of the museum. This largely took place in the green room, where you could even self-conduct his pieces (we did this with his Midsummer Night’s Dream) and choose how loudly each instrument should be played and even the type of venue it would be played for.

Going into the Mendelssohn House, I knew there were mixed accounts of the relationship between Fanny and Felix. Fanny was the oldest of the Mendelssohn children, born 4 years before Felix. She was also a composer and played piano and Felix supported her composition — but only in private. Felix and Fanny lived in Germany in the same era as Clara Schumann (and actually were good friends with the Schumanns later in life) and during that time, a woman would play piano as an erudite hobby to imply higher social status, not as a career. This was a notion that impacted both Clara and Fanny (albeit in different ways). Both Felix and his father discouraged Fanny from showing her compositions in public and under her name. One of the most hotly debated issues arising from this is that Felix would play his sister’s pieces under his own name. Some, erring on the more favorable side of the debate will say that this was a way for Felix to get his sister’s music out there, even if she couldn’t take credit for it. Others argue that he purposefully stifled her public exposure out of sexism and a fear of competition. I believe both arguments have evidence backing them. For example, the first is supported by the fact that when Felix played for Queen Victoria and she requested one of Fanny’s lieder (“Italien”), he confessed to his sister having composed it. On the other hand, while Felix supported Clara Schumann’s public performance and composition career, he suppressed Fanny’s, leading one to wonder why his response towards his sister was so different. Was he intimidated by her? Did he see her innate talent as a threat? Overall, the relationship between the two siblings was quite positive, with Fanny speaking highly of him and occasionally depending on his praise to continue composing. In some of her letters (she wrote so many, that on her floor of the Mendelssohn house, there was a whole room dedicated to them), she confessed that if Felix didn’t believe her compositions were worthwhile, she would stop composing altogether. However, despite their close relationship, occasionally Fanny rebelled and played her own music much later in her life.

The Mendelssohn family also had an interesting relationship with religion, namely Judaism. Their grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn, was a “preeminent Jewish philosopher of the German Enlightenment” (Library of Congress) in a period where Jews were largely marginalized. Given the challenges of being Jewish and social/economic advancement during that time, the Moses Mendelssohn family children (the generation before Felix and Fanny) practiced different faiths. Of the six, two remained Jewish, two converted to Catholicism, and two converted to Protestantism. One of the two who embraced Protestantism was Felix and Fanny’s father, Abraham. There’s so much more to say on this topic, but this post is becoming quite long and I could write a whole book on this, so I’ll stop here for now.

Can’t wait to keep learning about the Mendelssohns and their beautiful music!

Gabrielle

https://www.loc.gov/collections/felix-mendelssohn/articles-and-essays/felix-mendelssohn-and-jewish-identity/

Gabrielle, Thanks for sharing your thoughts about Felix and Fanny—and our wonderful visit to the museum. She is a wonderful composer, but indeed the relationship with Felix is complex. It was certainly challenging for women composers then, as always; but in a very short life (37 years), Mendelssohn accomplished an extraordinary amount, not the least of which was his support of earlier music (Bach and Handel).

I wonder about the podcast you mentioned——it sounds as if they were being rather dismissed of Mendelssohn. In dealing with these figures from the past, it is important to seek a balance between being overly worshipful or mocking them in some way. It sounds as if maybe this discussion erred a bit on the latter side?

So much to say about the question of Judaism in the Mendelssohn’s. Scholars have veered from claiming that he retained his Jewish faith despite the conversion of his parents to those who claimed he was fully converted and truly had no interest in Judaism. I think the truth is somewhere in the middle.