Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公 ––Theatrical Juxtaposition and Performative Superimposition

Well-known for his highly personal and provoking styles, Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公 (b. 1933) occupies a special place in the history of postwar Japanese photography. Hosoe learned photography at a young age from his father, who was a priest in a Shinto shrine who became a commercial photographer.[1] In 1954, Hosoe graduated from the Tokyo College of Photography, where he later returned in 1975 to serve as a professor of photography.[2] Hosoe began to attract wide attention after his 1960 solo show, “Man and Woman,” in which he explored forms of human bodies––a favored theme that he would continue to investigate in his later works including the photographs on display in this section.[3] One characteristic that distinguishes Hosoe’s photographic practices among contemporary Japanese photographers is his close collaboration with other artists, actors and writers, which makes his works an epitome of the lively artistic exchanges in the second half of the twentieth century in Japan. His particular interests in collaborating with dancers and actors to create staged and semi-staged photographs also give his works a unique sense of Surrealist theatricality. As curator Simon Baker commented, Hosoe accepted “more completely and honestly than any other artist of his generation the absolute equilibrium at the heart of the relationship between photography and performance.”[4]

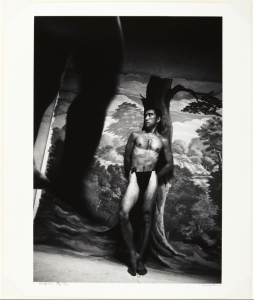

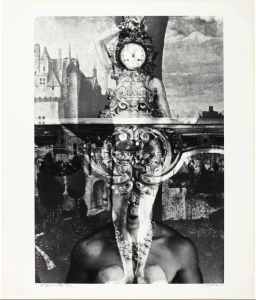

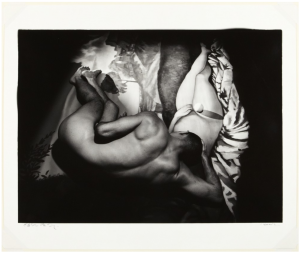

This section features three photographs by Hosoe, all of which are included in his photobook Barakei 薔薇刑 (“Killed by Roses,” later retitled “Ordeal by Roses”). In this group of photographs, Hosoe captures the model––the renowned writer and actor Mishima Yukio 三島由紀夫 (1925–1970) in juxtaposition with provocative references to Western cultural tradition and homosexuality. The collaboration between Hosoe and Mishima began in September 1961. After Mishima saw Hosoe’s photographs of Hijikta Tastumi 土方巽 (1928–1986)––the founder of the Ankoku Butoh 暗黒舞踏 dance who had adapted Mishima’s novel into a dance performance, Mishima connected with Hosoe through his editor and commissioned a photo session for his book, which then evolved into the much bigger Barakei project.[5] Hosoe and Mishima collaborated on this project between the fall of 1961 and the spring of 1962, photographing first in Mishima’s house and then in the deserted dance studio of Hijikata.[6] The resulted photographs were then compiled into a photobook under the title “Barakei,” one of eight titles proposed by Mishima and chosen by Hosoe when some works from the series were exhibited in January 1962 in the VIVO–associated “Non” exhibition organized by Fukushima Tatsuo.[7]

Unlike any conventional author photo, the highly stylized photographs in the Barakei series explore and reconstruct Mishima’s sexual and cultural identities through provoking means of juxtaposition and superimposition. Mishima was also happy to give the young photographer enough space to create something unconventional. The first time they met, Mishima told Hosoe: “I am your subject matter. Photograph me however you please.”[8] With Mishima’s consent, Hosoe used “whatever Mishima loved or owned to form a document on the writer” with the photographer’s own “interpretation and expression.”[9] Thus, the Barakei series is a collaborative performance by Mishima and Hosoe, in which reality is mediated by theatrical juxtaposition and superimposition of provocative cultural emblems. A representative of Hosoe’s career-long interest in the integration of photography and performance on the subject of human body, the Barakei photographs on display explore issues of homosexuality and cultural identity in “a kind of nude theater.”[10]

EXPLORE THIS SECTION

#33, Barakei 薔薇刑, 1961 (1963?), printed 1982

#33, Barakei 薔薇刑, 1961 (1963?), printed 1982

[1] Hosoe Eikoh and Lena Fritsch, “In Conversation with Hosoe Eikoh,” in Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography Since 1945 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 51.

[2] “Artist Profiles,” in Anne Wilkes Tucker, et al, eds. The History of Japanese Photography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 344.

[3] Lena Fritsch, “The Image Generation,” in Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography Since 1945 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 44.

[4] Simon Baker and Fiontán Moran, eds., Performing for the Camera (London, 2016), 18, as quoted in Lena Fritsch, Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography Since 1945 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 47.

[5] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” in Ivan Vartanian, Akihiro Hatanaka, and Yutaka Kambayashi, eds. Setting Sun: Writings by Japanese Photographers (New York: Aperture, 2006), 132–134.

[6] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 132, 134, 137.

[7] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 137.

[8] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 133.

[9] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 134.

[10] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 133.