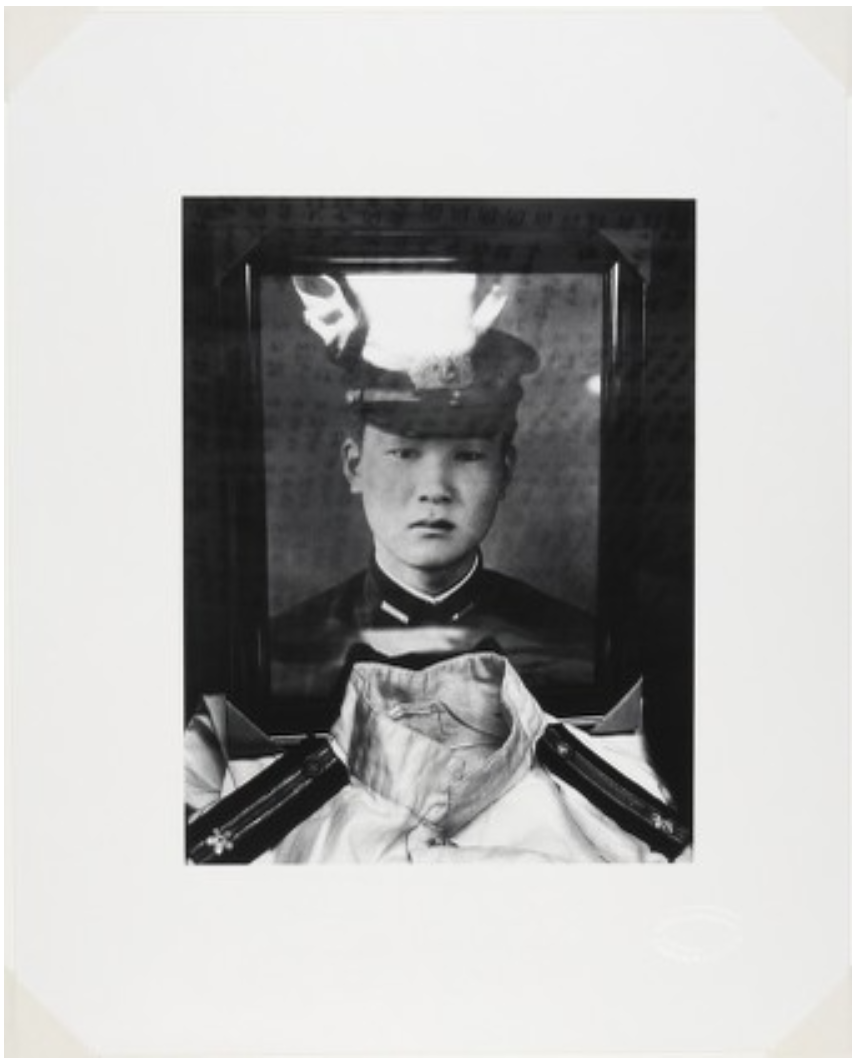

Kawada Kikuji 川田喜久治 (b. 1933)

Photograph and Personal Effects of a Kamikaze Commando, 1960–65, printed 1973

Gelatin silver print

image: 24.3 x 18.6 cm. (9 9/16 x 7 5/16 in.)

sheet: 37.9 x 30.3 cm. (14 15/16 x 11 15/16 in.)

Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Robert Gambee, Class of 1964

© Kikuji Kawada

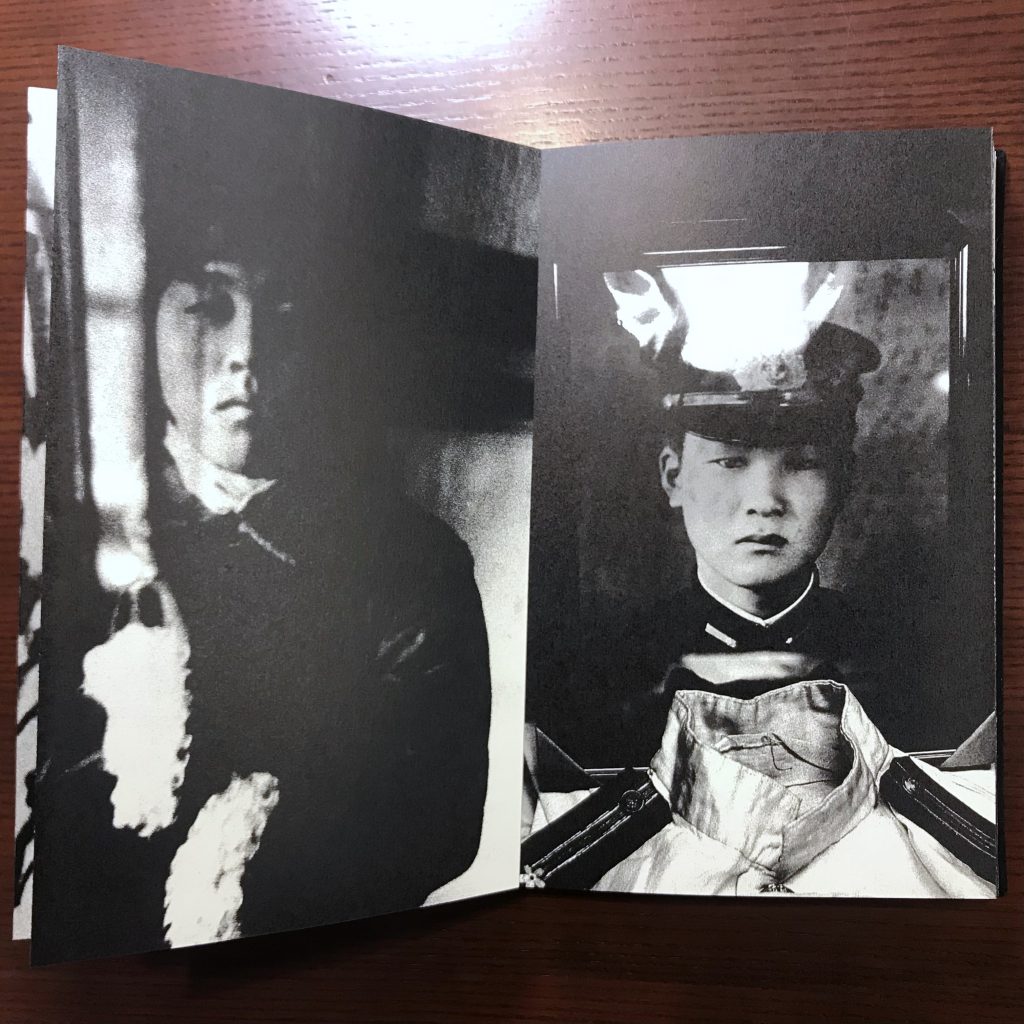

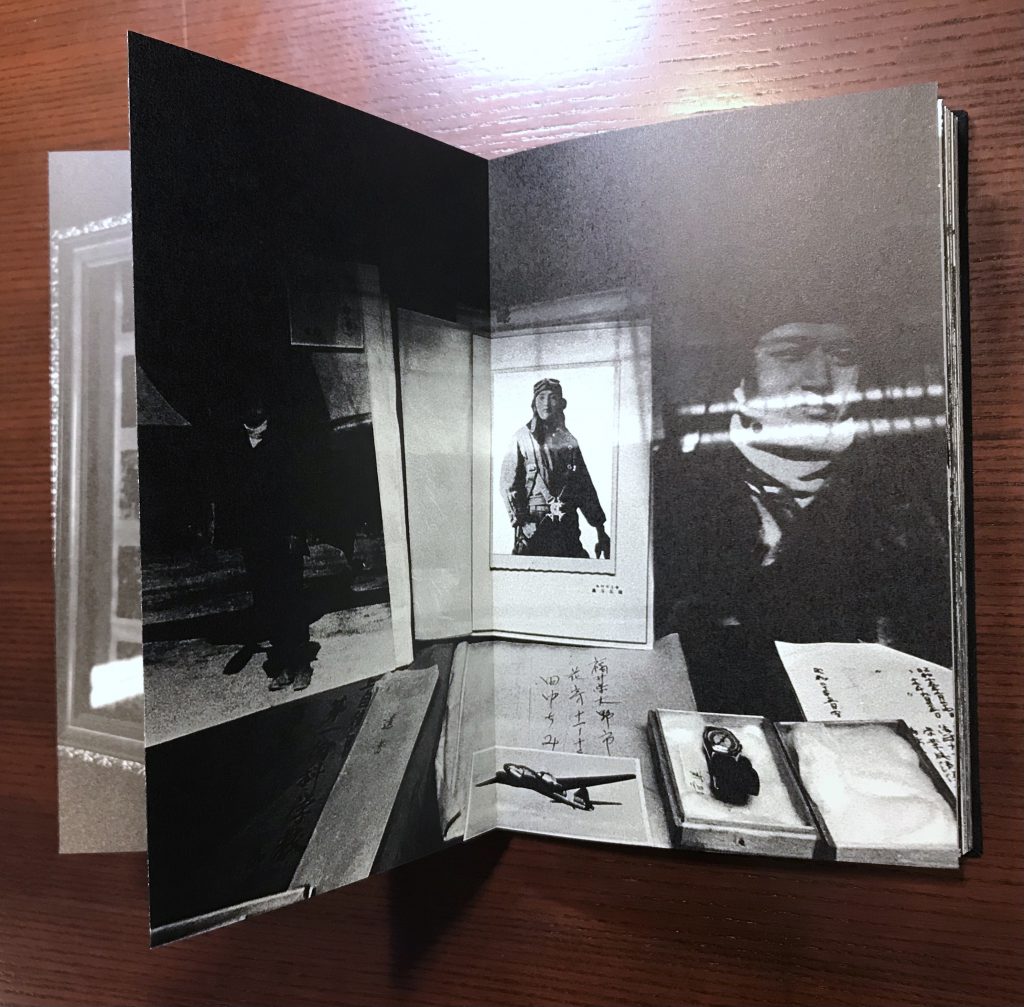

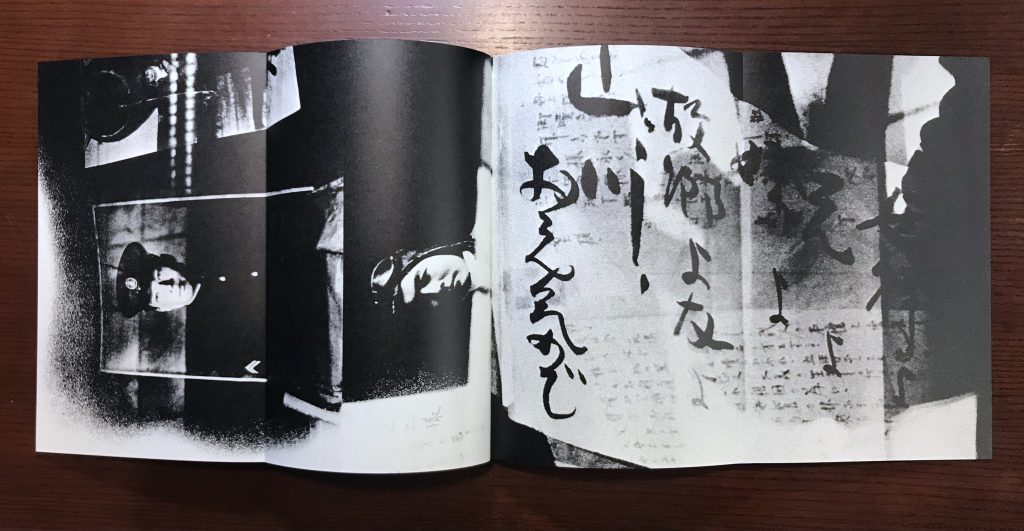

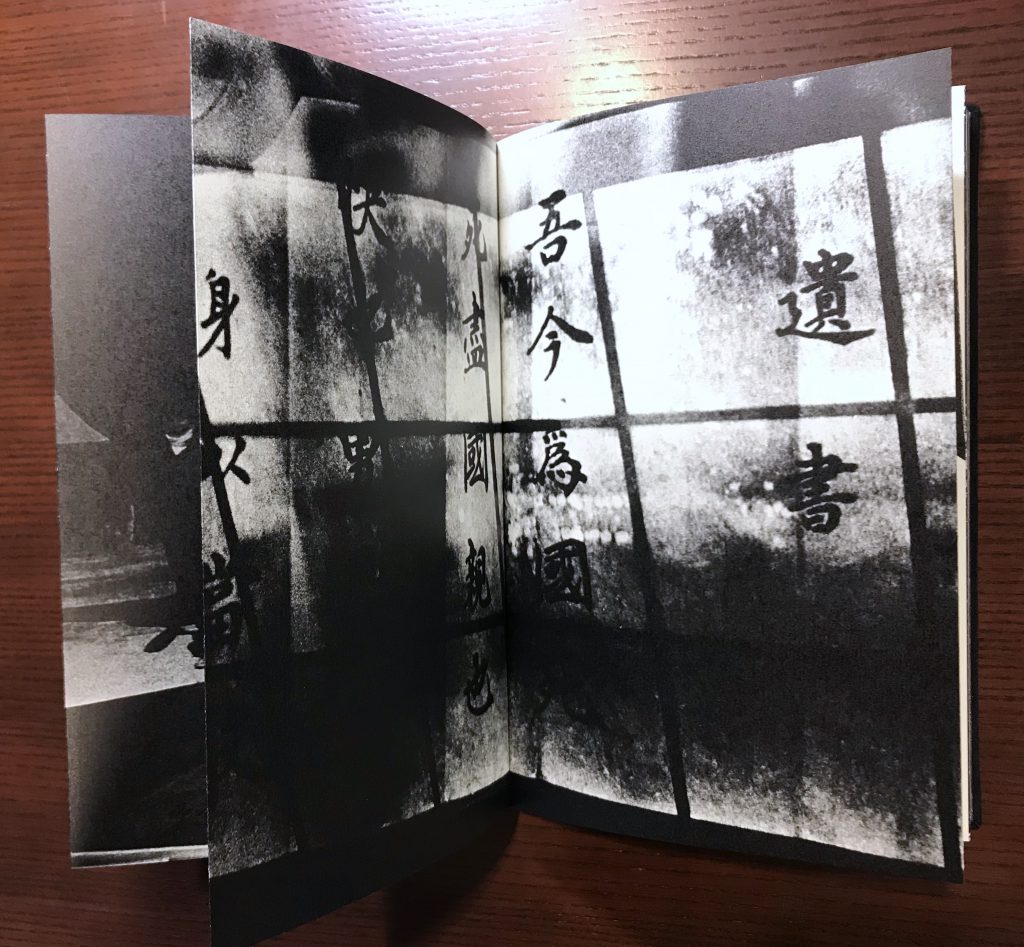

This photograph features a framed portrait of a young man in military uniform and a neatly folded uniform in front of the portrait. From the style of his uniform and the epaulet, it is possible to identity him as an aviator from the Kamikaze Special Attack Unit. The way that his portrait is arranged with a folded uniform suggests that the framed photograph is probably a memorial portrait for the deceased soldier. In a succinct, straightforward way, this photograph presents to the viewer a melancholic episode of a person’s life and a nation’s past. Curiously, on top of the upper part of the photograph, there seems to be superimposed layer of a blurred image of a piece of handwriting. In light of other similar photographs of personal objects in the series, this blurred image is most likely a reflection on a glass placed in between the photographed subjects and the photographer––Kawada probably took this picture behind a glass in a museum-like setting. The presence of this faint yet unignorable reflection calls attention to the physical and temporal gap between the viewer and an inaccessible past that the portrait refers to. In the photobook The Map, this photograph is grouped with other photographs that document similar personal objects left from the wartime––portraits, military manuals, personal writings including notes of last will (Fig. 7-1). Like the framed portrait of the Kamikaze pilot, most of these personal items were photographed behind a glass in a public, museum-like setting.

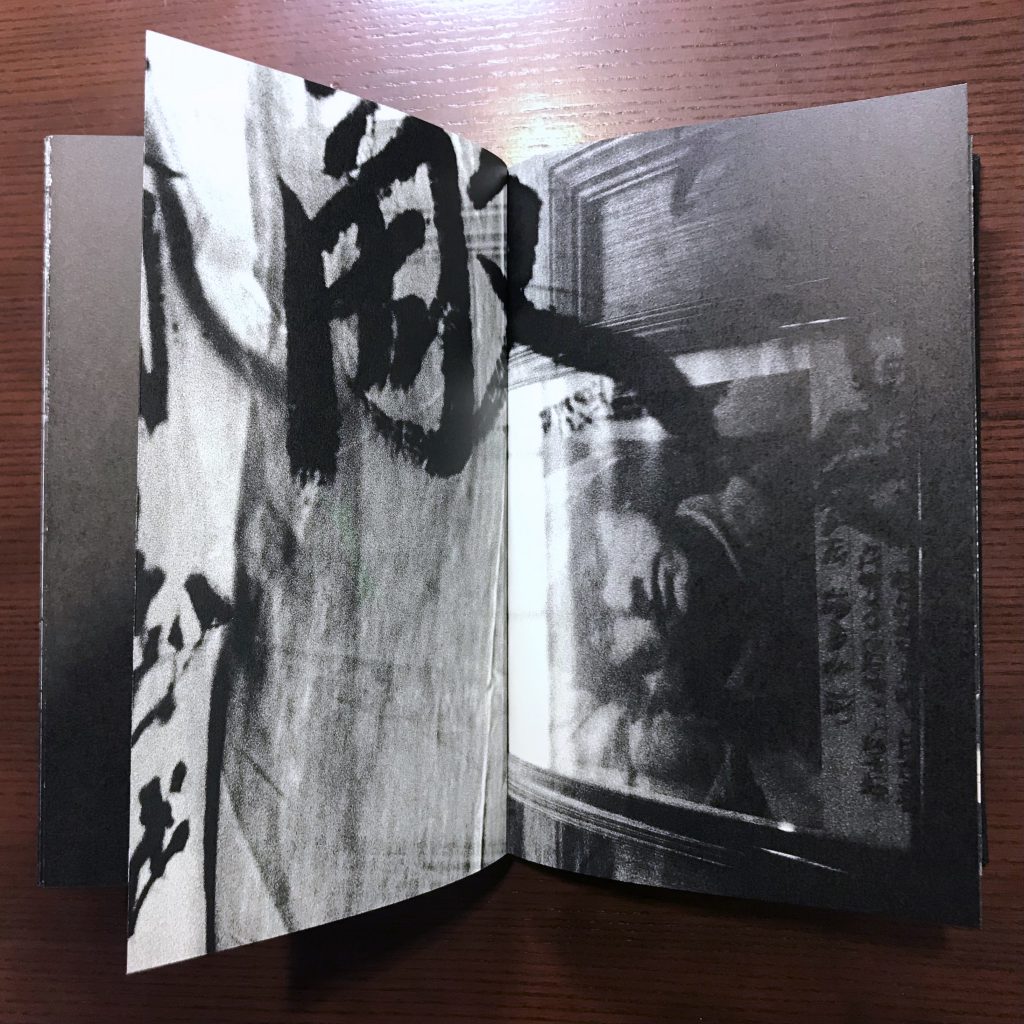

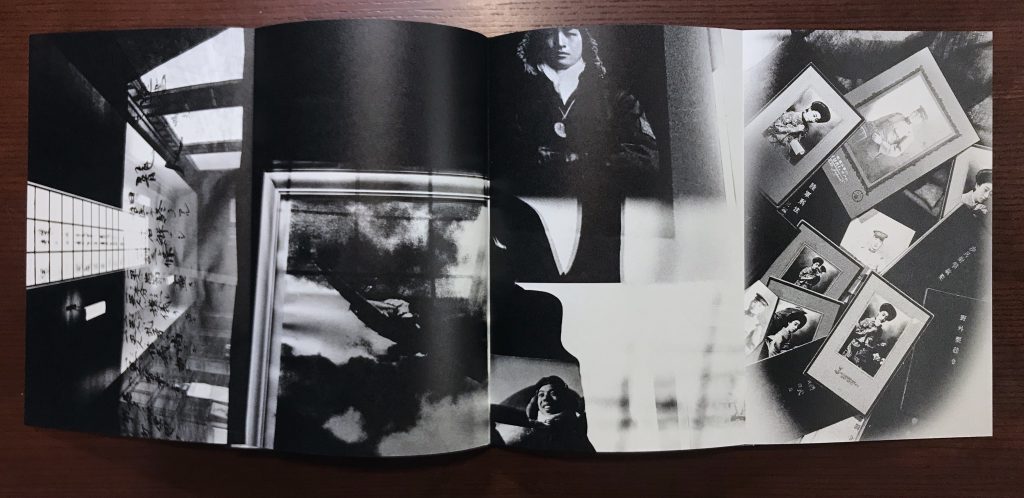

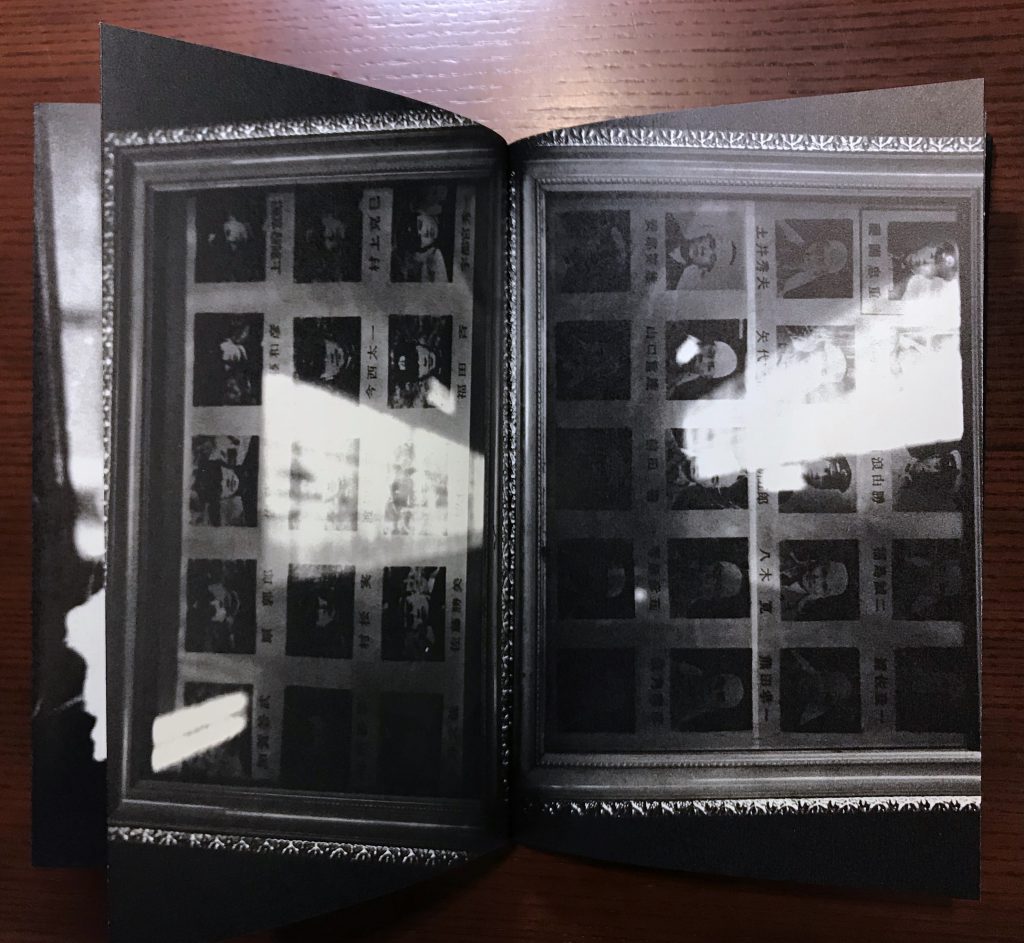

Fig. 7-1. Page 67–84 in sequence, from Kawada Kikuji 川田喜久治, The Map (Chizu 地図), 2005 reprint.

From the time when these personal objects were produced or actively used during the wartime to the publication of the photobook in 1965, these photographs about personal items in Kawada’s The Map refer to multiple temporalities and narratives that co-existed with each other. Though these photographed objects were often viewed as war relics with a sense of mourning in the postwar era, the brave and spirited words in the written texts and the uniforms that allude to personal and national honor as documented in the photographs, nevertheless, reveal a distinct state of mind among Japanese people and a different nationalist narrative during the wartime. When these private, personal objects were relocated to a public museum as historical documents after the war, their meaning was also forced to be readapted in order to fit an ambiguous postwar narrative about the country’s own violent past. The collision of the two narratives in these photographs poses the difficult question of how Japan should approach and remember the war.

In addition, the gradual development of the theme of personal objects in Kawada’s project of The Map adds another layer of temporality to these photographs on the production level. While Kawada’s 1961 solo show entitled “The Map” did not include any photograph of personal objects, in May 1963 issue of the magazine Photo Art, Kawada introduced a new type of photograph titled “Kinenbutsu” (記念物 Memorial Goods), which eventually evolved into one of the three main themes of the 1965 photobook.[1] This narrative of incorporating the photographs of personal objects into the photobook project impels one to ponder over the relationship between the personal memories carried by these photographs and a larger narrative of the war that the photobook explores. When the multiple narratives converge in the photographs of personal effects in the final photobook, the viewer creates yet another temporal dimension by reinvigorating the documented relics from the past through the turning of the pages and by probing into the irreconcilable temporalities in his or her particular social and cultural contexts.

Temporality played an important role in Kawada’s conception of the photobook project and photography in general. He once noted in an interview: “For The Map, I took photographs of different things over a period of five years. Japan changed greatly during those years, and I am interested in this temporality.”[2] As Kawada consciously messed around the idea of temporality in his works, the passing of time also bestowed upon his photographs new social and cultural connotations that refute any fixed, stable narrative––in Kawada’s words, “Photographic expressions can change dramatically over time.”[3] Through such experimentation with temporality in the photobook, Kawada has transformed the personal effects that he photographed into his own contemplation about Japan’s relationship with the war––as he commented on the project, “what lay beneath that was my perspective and way of thinking as I lived through the era.”[4]

[1] Maggie Mustard, “Atlas Novus: Kawada Kikuji’s Chizu (The Map) and Postwar Japanese Photography,” PhD dissertation (Columbia University, 2018), 71–74.

[2] Kawada Kikuji and Lena Fritsch, “In Conversation with Kawada Kikuji,” in Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography Since 1945 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 50.

[3] Kawada Kikuji and Lena Fritsch, “In Conversation with Kawada Kikuji,” 50.

[4] Kawada Kikuji, Interview, San Francisco Museum of Fine Arts, March 2016. https://www.sfmoma.org/artist/Kikuji_Kawada/.

Start the discussion