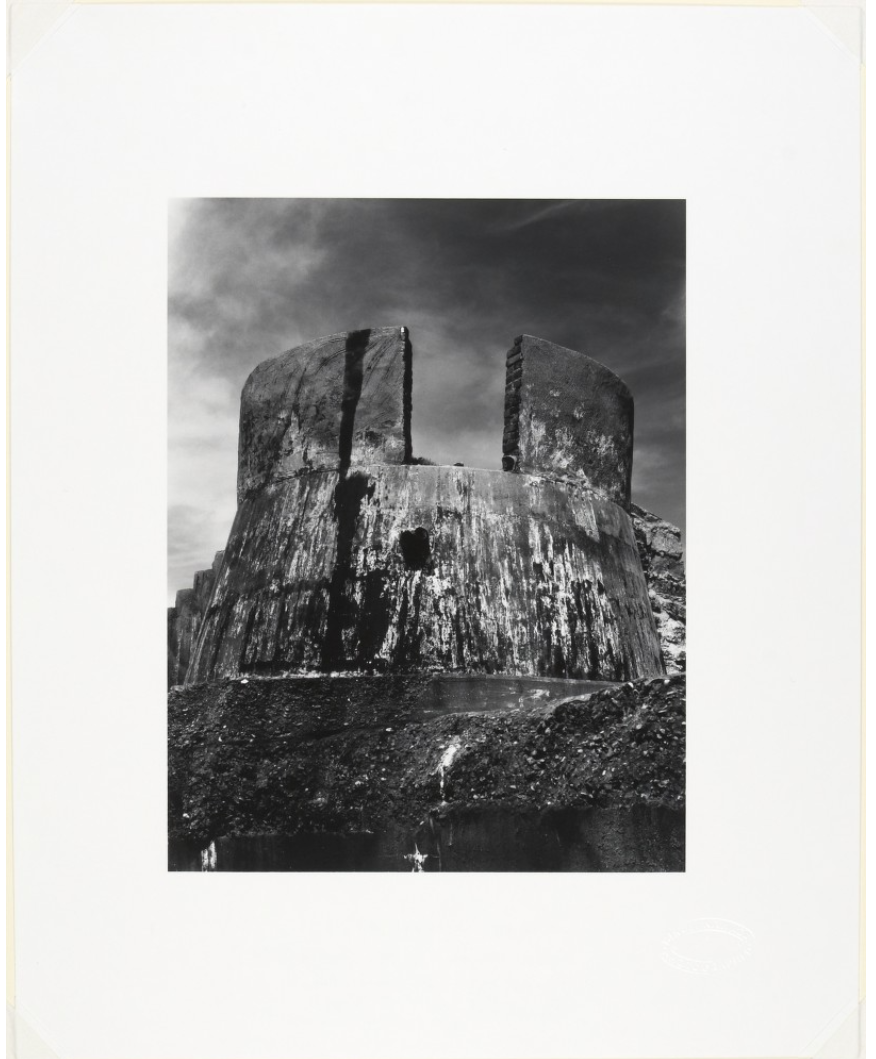

Kawada Kikuji 川田喜久治 (b. 1933)

The Ruin of a Stronghold, Atomic Bomb Memorial Dome, 1960-65, printed 1973

Gelatin silver print

image: 24.2 x 18.6 cm (9 1/2 x 7 5/16 in.)

sheet: 37.9 x 30.3 cm (14 15/16 x 11 15/16 in.)

Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Robert Gambee, Class of 1964

© Kikuji Kawada

In this photograph, Kawada captures the ruins of a desolate stronghold as a monumental relic of the wartime. The low angle from which Kawada took the photograph and the almost symmetrical placement of the anti-aircraft gun position in the picture highlights the monumentality of the stronghold. The sharp contrast and grainy quality of the photograph accentuate the texture of the decayed exterior surface of the stronghold, which denotes the rupture between the time of the military structure’s active service and the early 1960s when Kawada captured it. The “stains” on the wall surface, referred to as shimi by Kawada in Japanese, remain an important motif in the series of The Map that embodies the enduring stains that the war left in Japan’s postwar identity.[1] At the same time, the way that the deserted stronghold fills almost the entire photograph also detaches the structure from its surrounding environment, thus uncoupling it from any specific social and historical moment. This photographic style resonates with that of other photographs in The Map that record the ruins of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, often known as the A-Bomb Dome. The A-Bomb Dome is one of few surviving architectural structures near the hypocenter of the bomb’s blast and a central landmark of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park constructed from 1950 through 1964. The stylistic uniformity between the photographs of the A-Bomb Dome and that of the stronghold visually equate the status of the desolate fortification with that of a historical monument that memorializes the traumatic history of war in postwar Japan.

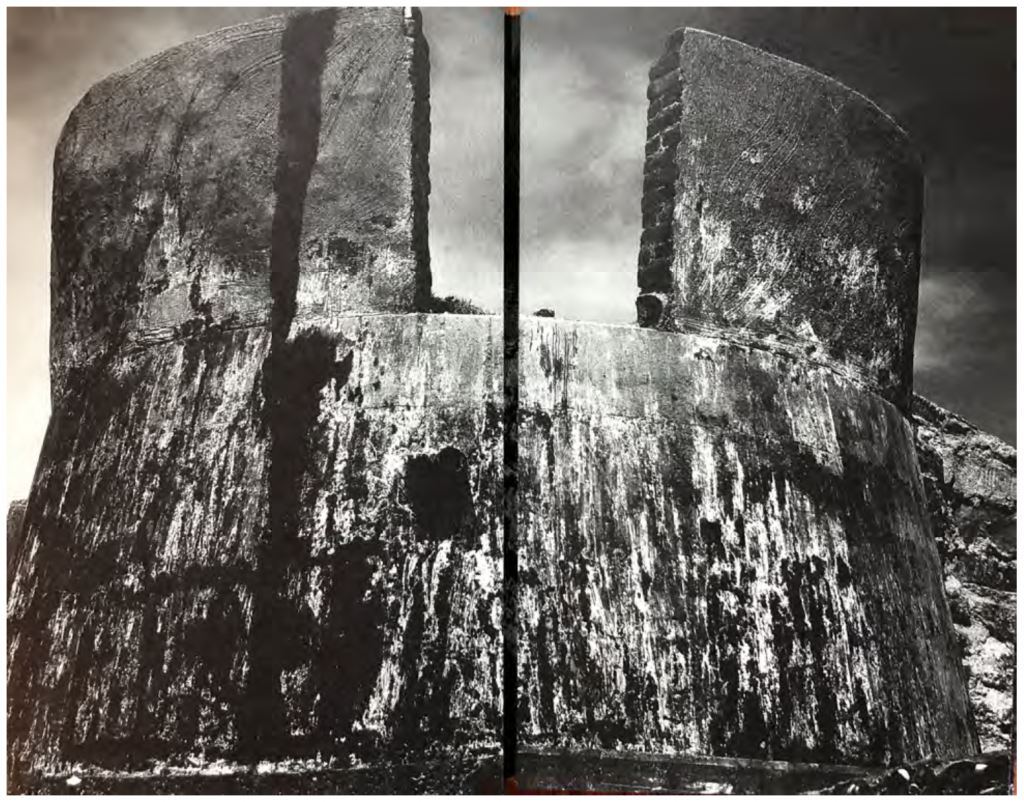

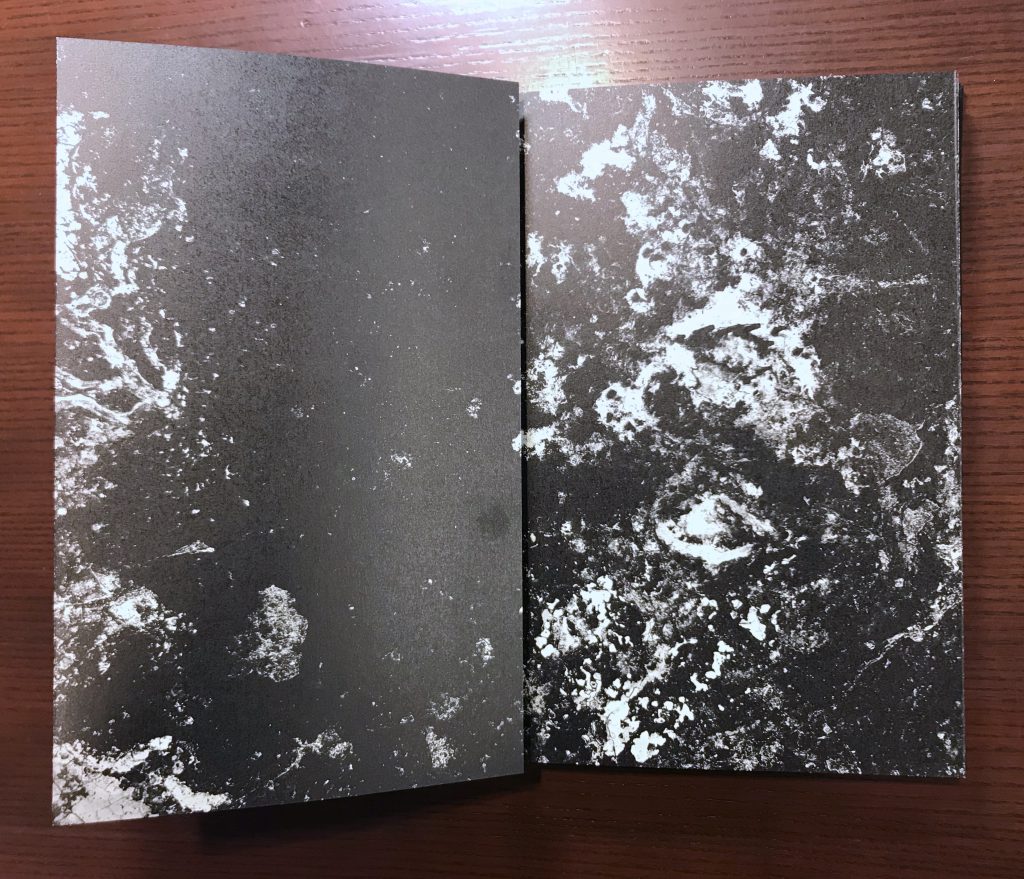

Fig. 6-1. Page 13 and 14 from Kawada Kikuji 川田喜久治, The Map (Chizu 地図), 2005 reprint.

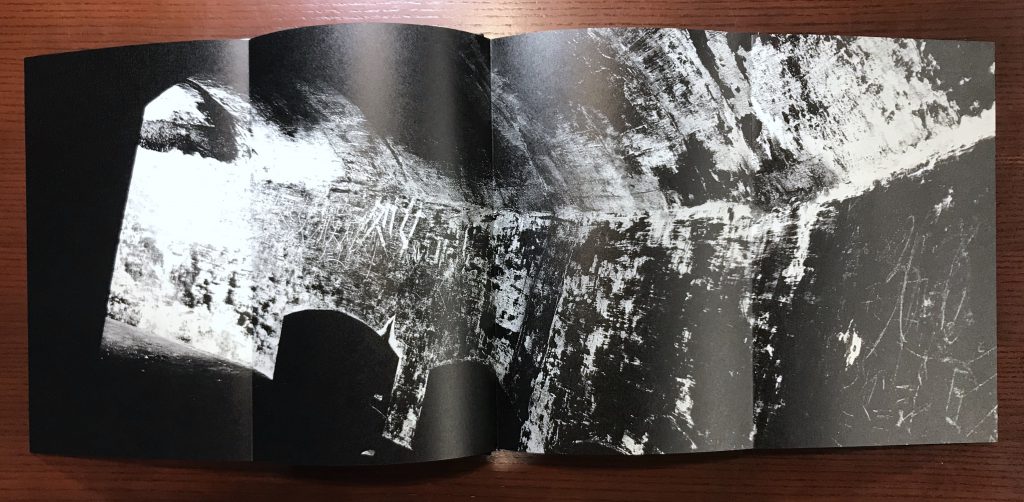

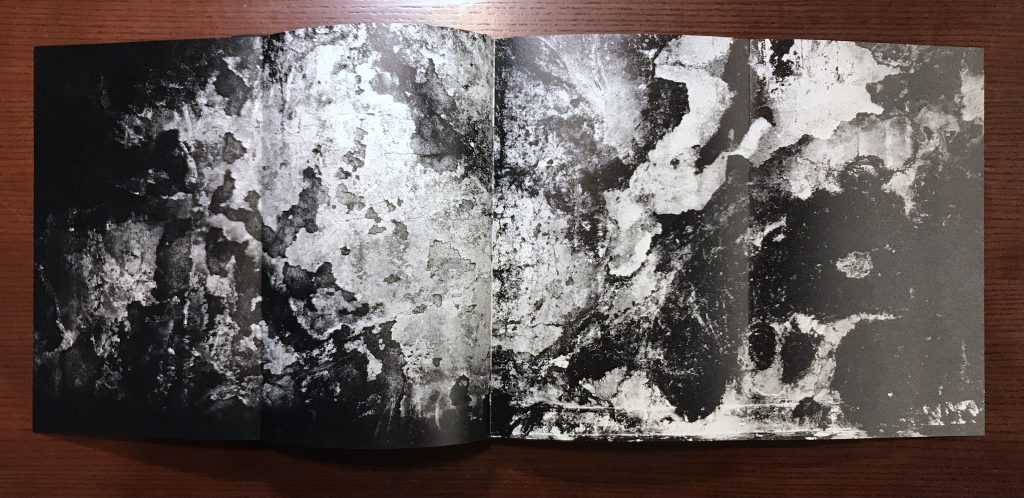

Fig. 6-2. Page 15–18 from Kawada Kikuji 川田喜久治, The Map (Chizu 地図), 2005 reprint.

The representation of this photograph of the stronghold in the photobook The Map further blurs the boundary between ruin and monument and constructs a “false” linear narrative as the viewer flips through the pages following the photobook’s kannon-biraki gatefold design (Fig. 6-1). In the photobook, this photograph of the stronghold is printed on two centerfold pages that can be unfolded into a four-leaf page of a shot of an interior scene (Fig. 6-2). The action of unfolding the pages resembles the experience of opening the double door of a kannon-biraki chest and thus creates a sense of spatial relationship between the exterior shot of the stronghold and the interior view on the horizontal page––the viewer unfolds the stronghold photograph as if he or she is physically entering into the stronghold to see its interior wall with rich texture. As one continues to flip through the next couple of pages, he or she gets to see some close-up photographs of the intriguing texture and stains on some surfaces in greater detail and in an increasingly decontextualized way, as if he or she is walking towards a wall inside the stronghold (Fig. 6-3).

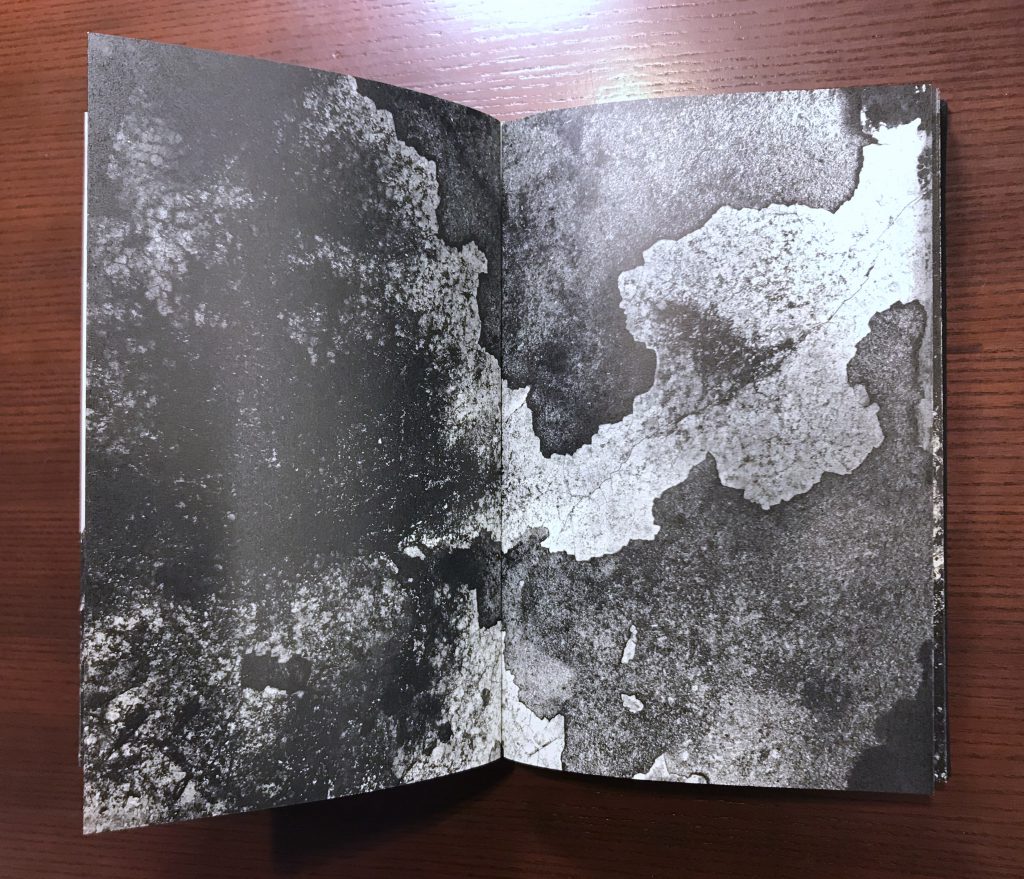

Fig. 6-3. Page 19–26 in sequence, from Kawada Kikuji 川田喜久治, The Map (Chizu 地図), 2005 reprint.

However, these photographs actually belong to three different contexts––the photograph printed on the four-panel page is a shot of a scribbled wall inside a Tochka, while the close-ups document the stains on the walls of the A-Bomb Dome. In this manner, Kawada made use of the kannon-biraki design of the photobook to dislocate the photographic views and construct a fictional spatial relationship among them. The linear characteristic of a book also facilitates the creation of a temporal experience along with a spatial one for the viewer. Photography’s ability of manipulating reality certainly lies at the center of Kawada’s experimentation with the medium. When he explained his fascination with photography, he commented about “the paradoxical character of photography” ––“you can take photograph of reality and they become a lie, but you also take photographs of lies and they become real.”[2] As he claimed, Kawada indeed obscured the boundary between truth and lie in his photobook The Map through the construction of a vivid yet fictional experience of space and time.

The subject matter of decayed texture and the way that it is represented in the photobook are also self-reflexive of the mechanism of photography.[3] Just like how the deteriorated texture serves as an indexical mark that the blast of atomic bomb left on the surface of the stronghold, a photographic image is also an indexical pattern imprinted by light. When Kawada’s photobook collapses the reality represented by the indexical stains in the photographs, it also questions the assumption about the relationship between photography and indexicality and ultimately the credibility of photography as a medium of documentation.

[1] The photographs of the deteriorating interior of the A-Bomb Dome are originally titled “stains” (shimi). Kawada discusses the motif of the stains in an essay written in 2005 titled “The Illusion of ‘the Stain’” 「しみ」のイリュージョン, published in a separate brochure along with the 2005 edition of the photobook, The Map. Kawada Kikuji, “The Illusion of ‘the Stain’”「しみ」のイリュージョン, in Chizu (The Map) (Tokyo: Nazraeli Press, in association with Getsuyosha, 2005).

[2] Kawada Kikuji and Lena Fritsch, “In Conversation with Kawada Kikuji,” in Ravens & Red Lipstick: Japanese Photography Since 1945 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 50.

[3] Maggie Mustard discusses the self-reflexivity of the stains in her dissertation: Maggie Mustard, “Atlas Novus: Kawada Kikuji’s Chizu (The Map) and Postwar Japanese Photography,” PhD dissertation (Columbia University, 2018).

Start the discussion