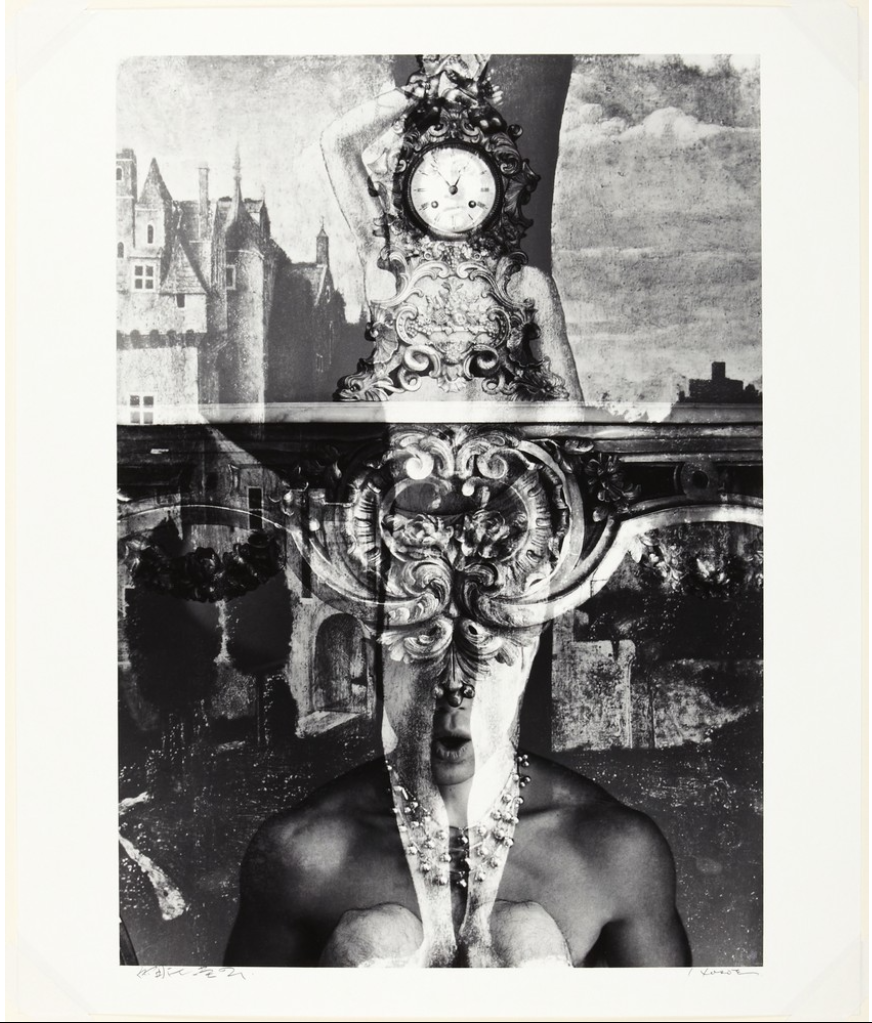

Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公 (b. 1933)

#29, Barakei 薔薇刑, 1961

Gelatin silver print

image: 54.5 x 38.4 cm. (21 7/16 x 15 1/8 in.)

sheet: 60.2 x 50.3 cm. (23 11/16 x 19 13/16 in.)

Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Susan and Eugene Spiritus

© Eikoh Hosoe

This photograph features a superimposition of a Renaissance painting of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian in the background and an image of Mishima in the lower half of the photograph. The background painting that spans the entire photograph is based on a fifteen-century painting by Antonello da Messina (Fig. 5-1). This painting follows a commonly seen composition of the subject matter but shows an unusual choice of depicting the martyr alone without his oppressors and in a suburban Venetian villa with a walled garden rather than the more public space of a town. This anachronistic choice may be interpreted as a form of “hortus conclusus,” which is often associated with the depiction of the Virgin and is probably appropriated here to underline the virginity of Saint Sebastian portrayed as a young boy. In light of Mishima’s writing about the homosexual connotation of the iconography of Saint Sebastian and Hosoe’s appropriation of it in other photographs in the Barakei series, the adoption of this particular painting must be intentional.

Fig. 5-1. Antonello da Messina, Saint Sebastian, 1476-77. Oil on canvas transferred from panel. 171 x 86 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Dresden.

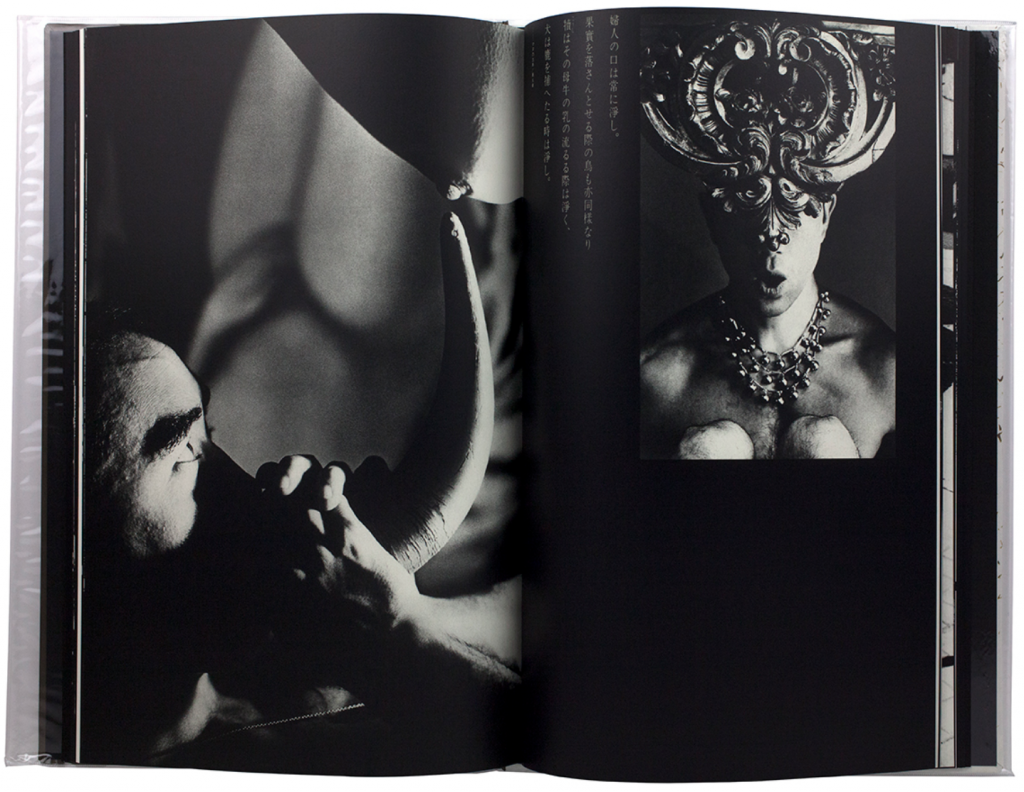

The way that Hosoe superimposes Mishima’s image on top of this painting further accentuates the undertone of sexuality of this photograph. A cropped version of the superimposed image of Mishima is also included in the photobook Barakei (Fig. 5-2). This photograph captures the upper torso of Mishima, with his knees in front of his chest and his upper face hidden by a flamboyant console table with a Régence-style shell ornament. This ornate table also resembles the capital of a column and recalls the depiction of broken columns in many Renaissance paintings including those that depict the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian. Furthermore, Hosoe superimposes this image of Mishima and the painting of Saint Sebastian in a careful way that evokes sexual, erotic interpretation: the shell ornament hides Saint Sebastian’s crotch; the space between Saint Sebastian’s legs is just enough to reveal Mishima’s nose and half-opening mouth; Mishima’s elaborate necklace is just of the right size to wrap around Saint Sebastian’s legs. Above this shell ornament is again superimposed an image of a clock in the same elaborate style that overlaps with Saint Sebastian’s head and chest. This complicated and meticulous superimposition brings together various kinds of motifs and blends different temporal, spatial, and cultural dimensions into one Surrealist, eroticized zone.

Fig. 5-2. Page from Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公, Barakei 薔薇刑, 2008 reprint.

This method of superimposition highlights an interplay of multiple forces that both construct Mishima’s self-identity and constantly destruct it. In the photograph, Hosoe deconstructs the different elements of Western art and homosexuality that constitutes Mishima’s self-identity and layers them on top of Mishima’s portrait. While Mishima’s identity is annotated by these motifs, they also compete with each other both visually and metaphorically. With their faces hidden, both Mishima and Saint Sebastian’s identities are on the edge of disappearing in the complicated layering of images: Mishima’s face is barely recognizable; and Saint Sebastian’s head is veiled by the clock image, as if this iconography has traveled through time to be recontextualized in a new discourse. At the same time, the images of the two men also resonate with and manifest each other––it is through the superimposition of Western and homosexual cultural emblems that Mishima’s cultural and sexual identities are discovered and contested at the same time. This strategy of constructing Mishima’s identity through its deconstruction echoes what Hosoe mentions as “a creative process through destruction.”[1] Via the almost “iconoclastic” superimposition, Hosoe “destructs” both the renowned author Mishima Yukio and the religious sainthood of Saint Sebastian in order to reconstruct a new photographic Mishima who emerges from the merging of the two.

[1] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” in Ivan Vartanian, Akihiro Hatanaka, and Yutaka Kambayashi, eds. Setting Sun: Writings by Japanese Photographers (New York: Aperture, 2006), 134.

Start the discussion