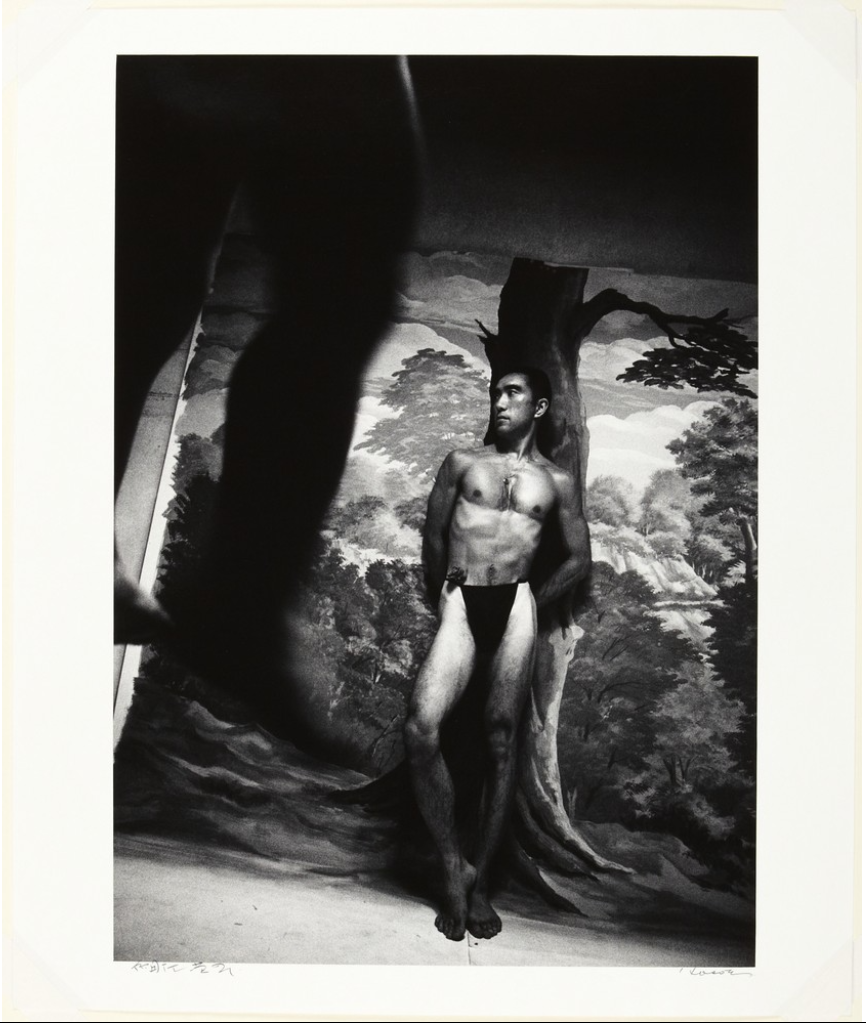

Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公 (b. 1933)

#34, Barakei 薔薇刑, 1961

Gelatin silver print

image: 54.4 x 38.3 cm. (21 7/16 x 15 1/16 in.)

sheet: 60 x 50.2 cm. (23 5/8 x 19 3/4 in.)

Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Susan and Eugene Spiritus

© Eikoh Hosoe

In addition to cultural identity, sexual identity is another underlying theme throughout the Barakei series. Mishima’s pose in this photograph alludes to the iconography of Saint Sebastian in Renaissance painting tradition. In front of a painted backdrop with a tree in the middle, Mishima stands in a contrapposto posture with his hands behind his back––a posture that clearly alludes to the frequently depicted iconography of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian with his hands tied to a tree (Fig. 4-1). Like how the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian is depicted in many Renaissance paintings, in the photograph, Mishima also exhibits a placid expression without any sign of mental or physical suffering. Even the backdrop of a painted landscape that Mishima leans against is in imitation of the style of Renaissance painting. The photograph is thus a reenactment of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastiana as portrayed in a typical Renaissance painting.

Fig. 4-1. Sandro Botticelli, St. Sebastian, 1474. Tempera on panel. 195 cm × 75 cm (77 in × 30 in). Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

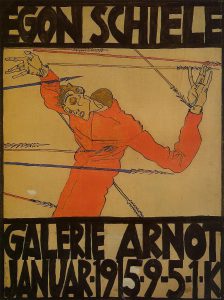

Fig. 4-2. Egon Schiele, Self Portrait as St. Sebastian (Poster), 1914. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.

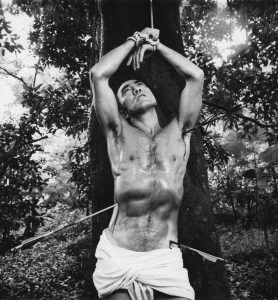

This photograph must be understood in relation to the cultural connotation of the iconography of Saint Sebastian in the 1960s. The religious iconography of Saint Sebastian has become associated with homosexuality by at least the nineteenth century.[1] His idealized seminude body and countenance were eroticized, and his suffering of arrows penetrating his body was compared to the difficulty faced by the LGBTQ groups. Subsequently, the iconography of Saint Sebastian also became a favored subject for twenty-century artists to explore the issue of sexuality (Fig. 4-2). Mishima must be well aware of this visual tradition. In his 1949 autobiographical work Confession of a Mask, Mishima states that he began to discover his own homosexuality upon seeing Guido Reni’s painting of Saint Sebastian (Fig. 4-3).[2] The borrowing of this iconography in the Brakei series might have also sowed the seeds of Mishima’s later collaboration with the photographer Shinoyama Kishin 篠山紀信 (b. 1940) in 1968 on portrait where he posed as Saint Sebastian in imitation of Guido Reni’s painting (Fig. 4-4). In light his self-reflexive investigation of his own homosexuality, Mishima was not just performing Saint Sebastian, but the cultural idea of Saint Sebastian in the twentieth century also became integrated into Mishima’s sexual identity—the cultural connotation of Saint Sebastian and the actual image of Mishima in the photograph both visually overlap and metaphorically intersect with each other. Therefore, Mishima’s pose in this photograph not only refers to a cultural symbol of homosexuality originated in Western, Renaissance visual tradition but also summarizes the author’s own private, self-reflexive journey about his sexual identity.

Fig. 4-3. Guido Reni, Saint Sebastian, ca. 1615. Oil on canvas. 127 x 92 cm (50 in x 36.22 in). Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Rosso, Genoa.

Fig. 4-4. Kishin Shinoyama 篠山紀信, Yukio Mishima as St. Sebastian, 1968.

What further complicates this photograph is the revelation of the setting of this photo session, which pulls the viewer out of the scenery of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian and calls attention to the image’s fictionality and performativity. Hosoe chose to shoot this photograph with a canted angle from a distance in a snapshot style, thus disclosing three of the four sides of the painted landscape backdrop and its hastily applied brushwork at the edges. In addition, the photograph also includes a blurry shadow of the legs of an unidentified jumping person in the foreground, which inserts a sense of motion and time into the seemingly timeless image of Mishima in disguise of Saint Sebastian. The inclusion of the edges of the painted backdrop against the studio’s white wall and the blurry legs in motion reminds the viewer of the creation process of this portrait of Mishima, which, though reminiscent of a timeless Renaissance painting, actually resembles a live performance on a theatre stage. By breaking the third wall for the viewer, this photograph is self-reflexive of the production process of the Barakei series. Thus, through the enactment of a cultural token of homosexuality––one that also marked the threshold of Mishima’s self-examination of his sexual identity, this photograph both restages Mishima’s private investigation of his sexuality into a public performance and reflects upon the performative nature of the photograph itself and essentially all photographs in the Barakei series.

[1] For a history of the eroticization of the image of Saint Sebastian, see: “Le Séducteur,” in Jacques Darriulat and Isabelle d’ Hauteville, Sébastien Le Renaissant: Sur Le Martyre De Saint Sébastien Dans La Deuxième Moitié Du Quattrocento (Paris: Lagune, 1998), 200-219.

[2] Mishima Yukio, Confession of a Mask, trans. Meredith Weatherby (New York: New Directions, 1958), 135. Guido Reni’s Saint Sebastian remains a central motif in Chapter 2, Confession of a Mask, 56–155.

Start the discussion