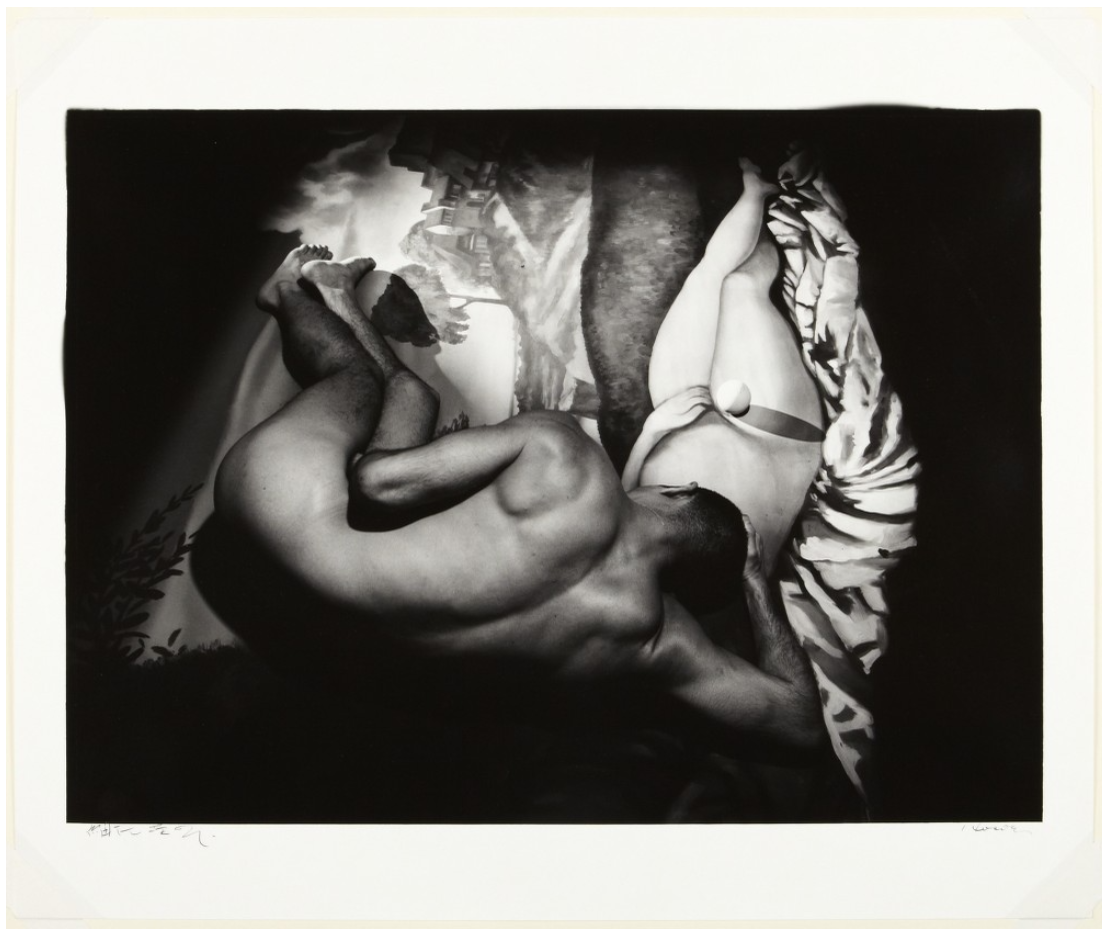

Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公 (b. 1933)

#33, Barakei 薔薇刑, 1961 (1963?), printed 1982

Gelatin silver print

image: 39.6 x 54.6 cm. (15 9/16 x 21 1/2 in.)

sheet: 50.3 x 60.2 cm. (19 13/16 x 23 11/16 in.)

Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, gift of Mrs. Max Adler

© Eikoh Hosoe

In this photograph, the writer Mishima Yukio is captured in complete nudity from the backside. He lies on a painted backdrop adapted from the Renaissance masterpiece Sleeping Venus by Giorgione with the upper half of the Venus removed (Fig. 3-1).[1] Mishima’s tanned skin contrasts with Venus’ pale skin in a way that recalls the color alternation of her body and the lawn behind her. Mishima’s head both overlaps with and replaces her absent head, and the male and female bodies roughly form a harmonious half circle, suggesting a subtle physical and emotional closeness between the two. Mishima’s body almost blends into the Renaissance landscape. To some extent, his body and the painting constitute another pictorial space that emerges from the darkness around the four sides of the photograph––another realm of reality above the Renaissance painting and within the photographic image.

Fig. 3-1. Giorgione, Sleeping Venus, c. 1510. Oil on canvas. 108.5 cm × 175 cm (42.7 in × 69 in). Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden.

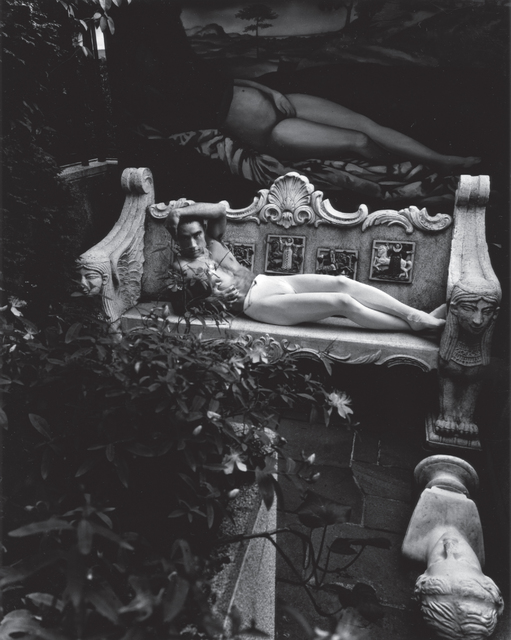

Fig. 3-2. Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公, No. 41, from Barakei 薔薇刑. 1961.

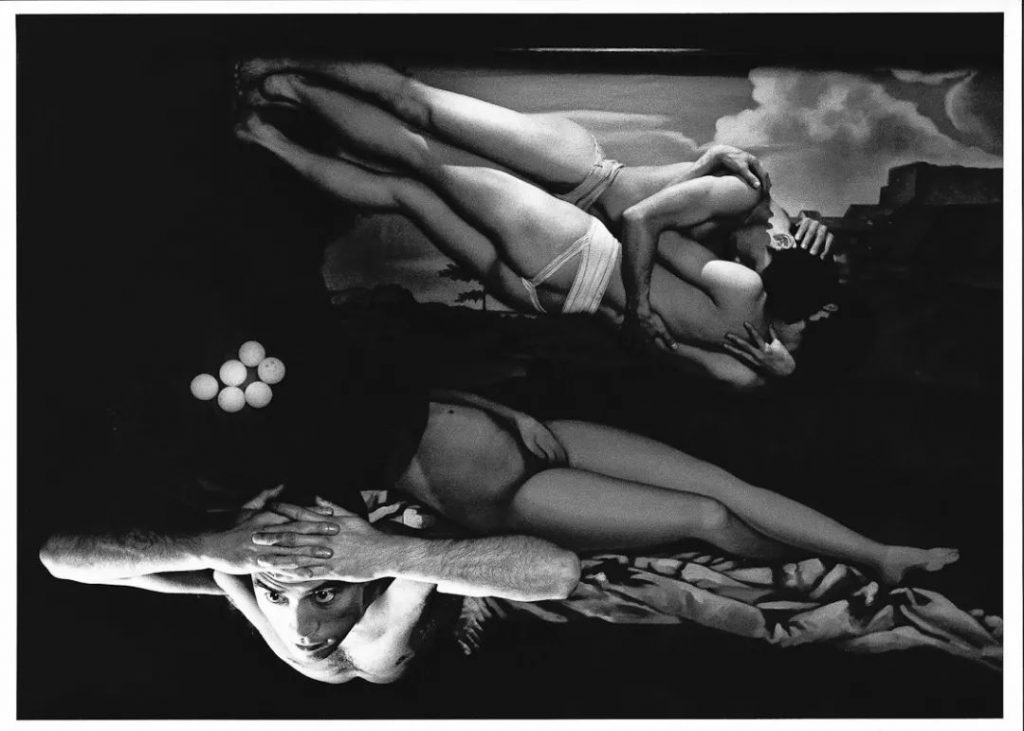

How should we understand this juxtaposition of Mishima’s nude body and the Renaissance painting of Sleeping Venus? One may gain more insights by examining this photograph in relation to other photographs from the Barakei series that also employ this copy of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus as a prop. In the No. 41 photograph from the series, for instance, Mishima lies horizontally on an elaborate Baroque-style bench in a garden with a classical sculpture bust (Fig. 3-2). Behind the bench hangs the painted backdrop after Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus. The partially reproduced body of Venus lies parallel to Mishima’s body. Instead of including any representation of the entanglement of the two bodies, both the photograph on display and the No. 41 photograph portray a parallel relationship between Mishima’s body and that of Venus. In another case, Mishima is seen in a posture of contemplation in the lower part of the No. 16 photograph from this series (Fig. 3-3). The body of Venus and another image of two embraced semi-nude male and female bodies are juxtaposed above Mishima’s head, as if these two images are what Mishima is puzzling over. More interestingly, Hosoe inserts a dark gap between the image of the two entangled bodies and the painted copy of Sleeping Venus, which is visually connected to Mishima’s body without any gap, thus highlighting the different kinds of relationship between the two groups of male and female bodies. In other words, in all three aforementioned photographs that group Mishima with the painted copy of Sleeping Venus, Mishima assumes a position of reflection that both engages with and is detached from Venus’ body. Such juxtaposition turns these photographs into Mishima’s performance of his own self-reflexive journey, during which he sees himself both with and against Venus’ body––in Hosoe’s words, “Mishima’s Venus would be borne by merging his flesh with the half-painted Sleeping Venus.”[2]

Fig. 3-3. Hosoe Eikoh 細江英公, No. 16, from Barakei 薔薇刑. 1961.

In addition to the reference to the issue of sexuality, this juxtaposition of the bodies of Mishima and Venus is also reflexive of Mishima’s attitude towards the rapid Westernization in Japan at the time. In his literary works, Mishima often advocates a return to the traditional samurai values and rejects Westernized modernization. In terms of formal representation, he also insisted on publishing his literary works following the Japanese vertical format.[3] Nevertheless, he also exhibited a passion in Renaissance art and clearly lived in a house with Baroque- and Rococo-style furniture and decorative objects. In fact, Hosoe decided to incorporate motifs from Renaissance art into the photographic project after Mishima mentioned about his favor of Renaissance art and showed Hosoe his copy of Bernard Berenson’s book The Italian Painters of the Renaissance and several reproduction of Italian Renaissance paintings that he owned.[4] Hosoe later explained that he believed that “the soul of a man [resided] in his property, and that his spirit [was] especially evident in the art and the possessions that [surrounded] him.”[5] Mishima’s ambiguous standing in between Japanese cultural tradition and its Western counterpart was artfully visualized through the juxtaposition of Mishima’s body and Western cultural symbols. In the photograph on display, Mishima’s staged contemplation in a “nude theater” and his struggling in real life overlap in the photographic image, turning the photograph into a documentation of a performance or a performance about what is there but hidden.

[1] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” in Ivan Vartanian, Akihiro Hatanaka, and Yutaka Kambayashi, eds. Setting Sun: Writings by Japanese Photographers (New York: Aperture, 2006), 134.

[2] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 137.

[3] Mishima compromised to have the second edition of Barakei (published on January 30, 1971) published in a Western fashion, with the pages flipped from right to left and the text read horizontally. Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 138.

[4] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 134.

[5] Hosoe Eikoh, “Notes on Photographing Barakei,” 137.

Start the discussion