Tōmatsu Shōmei 東松照明 (1930–2012)

Untitled, from the series 11:02, Nagasaki, 1962, printed 1988

Gelatin silver print

image: 41.8 x 51 cm (16 7/16 x 20 1/16 in.)

sheet: 28.5 x 40.8 cm (11 1/4 x 16 1/16 in.)

Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, gift of Robert Gambee, Class of 1964

© Estate of Shomei Tomatsu

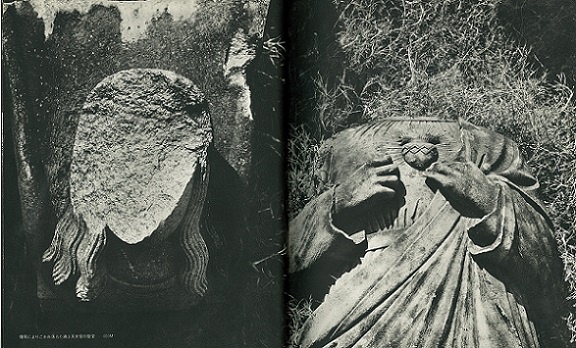

This close-up image of the scarred face of Yamaguchi Senji 山口仙二 (1930–2013), a survivor of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki in 1945 and later a leader of anti-nuclear movement, was taken in 1962 when Tōmatsu visited Nagasaki seventeen years after the bombing. Yamaguchi’s face was portrayed under a pointed light source from one side of his head. The resulted sharp contrast between dark and light helps reveal the refined details of the texture of his scars and creates an unsettling effect psychologically and emotionally. Tōmatsu recalled that when he first met with the atomic bomb survivors in Nagasaki, he felt so shocked emotionally that he could barely manage his camera and only wanted to leave.[1] Yet in this close-up image, Tōmatsu forces the view of what he once wanted to turn away from. By focusing on one fragmented and augmented body part, Tōmatsu invites the viewer to enter an extremely intimate memory about a traumatic historical event through the physical traces that it has forever left on Yamaguchi’s body. Unlike many other photographs that approach the atomic bombing as mainly social and historical event, Tōmatsu’s photograph acknowledges it as personal experience and bodily suffering that still haunt Nagasaki and those who have lived through the event in the unfolding present.

At the same time, this photograph also exhibits a calculated sense of emotional detachment. Yamaguchi’s face is obscured in the shadow, and so does his identity other than the label of a bombing survivor. His static pose, together with the straightforward composition and the simple, clean backdrop setting, creates a subtle sense of calmness and aloofness. To some extent, Yamaguchi’s scarred head is photographed almost like an emotionless monument, on which exist some marks that silently memorialize the traumatic historical event. This calculated emotional prudence interwoven with an extreme physical closeness enables the viewer to approach the photograph both as a historical archive from a distanced, collective perspective and as personal memories from an intimate, private point of view. This photograph thus becomes a site where Nagasaki’s past overlaps with its present and where the personal intersects with the collective.

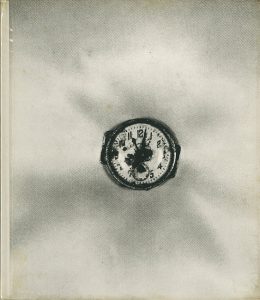

This photograph of Yamaguchi’s scarred face was included in Tōmatsu’s much-appreciated photobook 11:02, first published in 1966 and republished in 1968. Tōmatsu’s story with Nagasaki started on a winter night of 1960, when he ran into two representatives of Gensuikyō 原水協 (short for Gensuibaku Kinshi Nihon kyougikai 原水爆禁止日本協議会, the Japan Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs) in the office of VIVO and heard about their project of a photographic book for the market of the United States and Russia.[2] The fruit of this project was the book Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document 1961, which includes photographs of Hiroshima by the renowned photographer Domon Ken and those of Nagasaki by Tōmatsu, who was then still a junior photographer. After the completion of the Gensuikyō project, Tōmatsu returned to Nagasaki for several times in the following years, and photographed people, objects, and the land of Nagasaki in more idiosyncratic styles that distinguished Tōmatsu’s Nagasaki photographs from the numerous photographs about atomic bombings at the time. These photographs, along with some that were already included in Hiroshima-Nagasaki Document 1961, were compiled into Tōmatsu’s photobook 11:02, the title of which refers to the local time when the atomic bombing took place in Nagasaki––as the first photograph of the photobook shows, for many people in Nagasaki, their time stopped at 11:02 am on August 9, 1945 (Fig. 1-1).[3]

Fig. 1-1. First page of Tōmatsu Shōmei 東松照明, 11: 02 (11時02分), 1966.

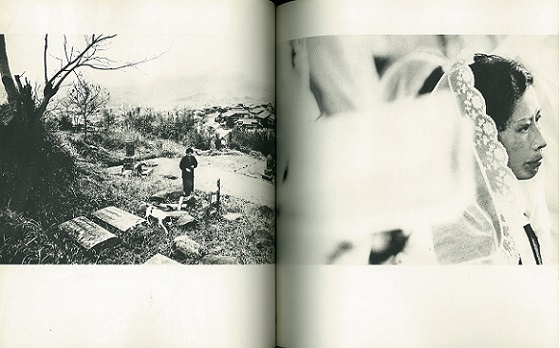

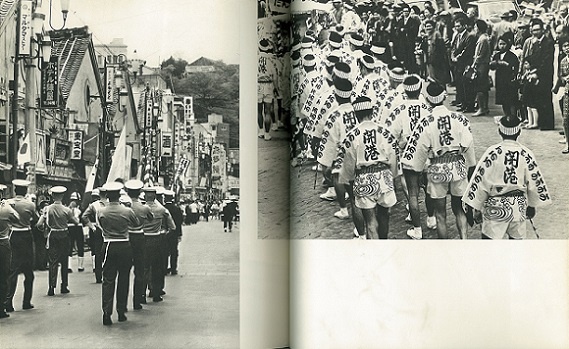

Fig. 1-2. Pages from Tōmatsu Shōmei 東松照明, 11: 02 (11時02分), 1966.

In both the single photograph of Yamaguchi’s scarred face and the photobook 11:02, Tōmatsu’s mediation of the subject matter is multi-layered. In the photograph, Tōmatsu uses extreme close-up, unexpected angle and high contrast to elicit an intimate and unsettling psychological effect blended with a subtle sense of emotional caution, which provokes the viewer to reflect on a traumatic past hidden within the shadow of the present. In addition, the way that Tōmatsu juxtaposes shots of Nagasaki’s everyday scenes in the early 1960s and the survivors’ scars, architectural ruins, and broken personal items from the 1945 atomic bombing in the photobook 11:02 further demonstrates his strategy of layering different temporal dimensions, on the one hand, and personal and collective memories, on the other hand (Fig. 1-2). The rich symbolism in both the photograph and the photobook as a whole recontextualizes the photographed subject into the photographer’s personal contemplation about the interplay between historical and present Nagasaki, and between collective and individual memories.

[1] Leo Rubinfein, “Shōmei Tōmatsu: Skin of the Nation,” in Leo Rubinfein et al, eds., Shōmei Tōmatsu: Skin of the Nation (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2004), 27.

[2] Leo Rubinfein, “Shōmei Tōmatsu: Skin of the Nation,” 25–26.

[3] Ilzawa Kōtarō, “The Revolution of Postwar Photography,” in Anne Wilkes Tucker, et al, eds. The History of Japanese Photography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 219.

Start the discussion