This exhibition features a collection of artworks that can change how we think about time in reference to change in the landscape. Geological time is usually seen as something purely organic, slow, and, for the lack of a better word, “natural”- meaning that humans do not have a hand in it. Mountains take thousands of years to erode, ecosystems take even longer to form, natural resources are even older than the Earth we know today, and there is no way we will run out of those!

But this collection of art shows us otherwise. It shows humans, or machines, as “geological agents”, authors capable of rewriting the landscapes, and the environment itself. They hint at the possibility of an anthropogenic era, where humans have created an entirely new natural world that is somehow even less predictable than the one before. They collapse the Strata, the layers of deep time we scratch every time we go mining for something new (or rather really old) to exploit. Our relationship to the organic, geological past, and how our environments have and will be shaped, should be closer in kin in our minds than it has been. Our care for the climate is based on our relationships with it, so we should learn the relationship of how our landscapes experience change, whether the geological agent is nature or it is us. Deep time is often too large and long to be completely fathomable, but the presented works below seek to collapse it and make it worthy and capable of being held in the mind.

The idea for this exhibition first sprouted while reading “Sites of time: organic and geologic time in the art of Robert Smithson and Roxy Paine” by James Housefield, from the 2007 journal release by Cultural Geographies, which usually publishes papers on the landscape and geographical issues. Both Paine and Smithson are the artists mainly used in this curation, since both artists engage the natural world, and its change, in different ways. But both, in the end, collapse the strata.

Roxy Paine, Erosion Machine, 2006

Paine’s Erosion Machine is programmed to viciously spit jets of air and grit at a sandstone block, painfully eroding it away like a natural cause would. But the cause is not natural, it is something of manmade creation. Through this machine, Paine discusses the Anthropocene, meaning that the actions humans take are creating a new nature, not dictated by geological time but rather our own. Paine constructs a new geological time-one that is palpable for us to fathom change of our environment on.

The data Erosion Machine runs on, to wither away the sandstone, is actually 1980s weather records from Binghamton, New York. The arm moves hypnotically across the sandstone, almost human-like, uncanny even. It creates marks reminiscent of actual geology- riverbeds, mountains, valleys, fields. Furthermore, it looks like these marks were made over time, perhaps ancient. But for Paine time is of the essence, and evermore urgent. The arm rewrites the landscape right before our eyes.

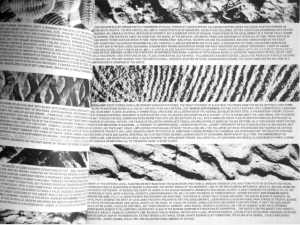

Robert Smithson, Slate Grinds, 1973

This late work of Smithson’s is concerned with the mark making on the geological landscape, in a similar way to Paine’s Erosion Machine. Man becomes a “geological agent”, a term Smithson often used in his writings to describe himself in relation to his material. The use of the material of slate also become important, since the rock is a sediment formed by volcanic activity thousands upon millions of years ago. This material is connected to the formation of our very planet, and Smithson shows us that he can manipulate the slate, becoming an agent of change that does not abide by the thousands of years erosion usually takes to be noticeable.

Roxy Paine, Erosion Machine (Sandstone)

This is the sandstone after it has done its time on the Erosion Machine. It most definitely looks like a mini-landscape, with mountains, valleys, gorges, highs and lows. Even after the movement of the machine is removed, the object of the sandstone still feels kinetic, like it has a history of why it is like that. In placed within the context of its history not being long, considering it was made in a machine made to erode, the construct of time becomes small. Our relationship to how the environment can be changed becomes more accelerated.

Michael Heizer, Double Negative, 1969-1970

Double Negative is too large to be encompassed in a single photo; it can only be fully seen on Google Earth, from the far away aerial. The piece is essentially a two part trench created with the use of explosives in the rocky landscape of Overton, Nevada. Heizer is known for his large scale Earth works, the largest being City, which is also based in Nevada, took 50 years to construct, and is the largest contemporary art work (it is over a mile long). The thing about Heizer’s work is that you can not really tell when it was built, how it was built, or if it is even built by a human. Double Negative could very easily be a natural phenomena. One could be reminded of the Siq in the ancient city of Petra, located in modern day Jordan. The famous gorge was a landscape feature highly contested for a while, since it seemed it could be both manmade or natural.

Roxy Paine, Crop [Poppy Field], 1997-1998

This work seems to aesthetically and visually be on the opposite side of the spectrum to Erosion Machine, but it has similar motifs. Crop is a carefully constructed dirt rectangle of poppies in different life and death stages, some even dripping opium. The material list is:. Lacquer, epoxy, oil paint, pigment, plaster. Each flower was cast meticulously, put onto wire, and then carefully placed and painted. The organic life stages of the poppy become completely inorganic and staged, made by a “geologic agent” that is not nature or deep time.

Robert Smithson, Strata: A Geological Fiction (1970-1971)

Strata is an art essay Smithson wrote for the art magazine Aspen (Winter 1970-1971). The paragraphs of the essay are placed between fossil layers of the Earth, with each section being titled a different period of geological time. Smithson is flattening the past, present and future of our landscape. Smithson tries to think through all the layers, or strata, of time here, and it is interesting to think about this piece in reference to a lot of his other works.

Check out this digital copy: https://www.ubu.com/aspen/aspen8/strata.html

Roxy Paine, Imposter, 1994

This is the first of Paine’s large Dendroids, the series of work he is probably most famous for. The life size tree was placed in a forest in the South of Sweden. Through using the form of a tree, but making it stainless steel, the piece is both simultaneously something natural (tree) and industrial (a metal, robot arm or tendril). Like with Erosion Machine, and all his other work, frankly, Paine confuses what is nature and what is a product of the human hand- or, bettermore, a product of our machines.

Roxy Paine, Maelstrom, 2009

This is arguably Paine’s most famous work, which was installed on the prime sculpture grounds of the MET’s rooftop. The sculpture is approximately 130 ft long,made of stainless steel, and visitors were able to walk through it. Maelstrom gets at the same things all of these other works presented have gotten at, but the most important part of this one is its backdrop: of New York City. Central Park, and the buildings beyond, serve as a fitting and ironic backdrop for this art work about the interaction between nature and our technology/industry, and the eventual technological anthropocene singularity.