“I spent my life trying to understand the Yanomami and transmit what I understood… To understand people is to understand life.” — Claudia Andujar

The Amazon Rainforest has long been a focal point of the international climate discourse. Frequently described as the “lungs of the planet,” entities such as the Paris Climate Agreement, Conference of the Parties, and World Wildlife Fund place great emphasis on reducing deforestation and maximizing the carbon capture capabilities of the Amazon Rainforest. This exhibition reimagines Amazonia through the lens of the Yanomami people, one of the largest indigenous groups in Amazonia, and challenges climate narratives that reduce the forest to a carbon sink. Showcasing works by photographer Claudia Andujar and Yanomami artists Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami and Ehuana Yaira, this exhibition foregrounds Yanomami relations to the forest as cultural, spiritual, and political.

Claudia Andujar, born in Switzerland, began her photography career in 1955 in Brazil and has been in collaboration with the Yanomami people for over five decades. Andujar’s relationship with the Yanomami was established through her activism against Brazil’s military dictatorship in the 1970s and her friendship with Davi Kopenawa, a Yanomami shaman and leader. As the dictatorship implemented development projects that exploited natural resources in the Amazon and disrupted Yanomami communities, Andujar became an outspoken critic, founding the Commisao Pro-Yanomami (CCPY) in 1978. She dedicated herself to defending the Yanomami’s territorial and cultural rights, and after 14 years, the CCPY succeeded in obtaining demarcation of Yanomami territory.

Throughout the five decades of Andujar’s relationship-building and activism with the Yanomami, her photography raised global visibility around the Yanomami struggle to protect their land, people, and culture. By shedding light on Yanomami cosmology, Andujar demonstrates that the Amazon is not only an ecologically diverse region, but also the home to expansive cultural and spiritual worlds. Foregrounding issues such as public health, land dispossession, and economic exploitation in the Amazon, Andujar brings attention to the need for climate solutions to reckon with the social and political histories embedded in the forest.

This exhibit pairs Andujar’s photographs with works by two Yanomami artists, Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami and Ehuana Yaira. Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami is the son of a Yanomami shaman, and his works visually represent Yanomami cosmology. According to his artist statement, “I am inspired by the words of the shamans…When they hold their shamanic sessions, I listen to their chants, I record all those words in my mind and then I transform them into drawings.” Through his art, Mokahesi captures dimensions of the Yanomami’s relationship with the forest that are only visible to shamans and presents their visions on ecological and spiritual balance.

Ehuana Yaira is an artist, activist, and author of Yɨpɨmuwi thëã oni, Words about Menstruation, the first book written by a woman in the Yanomaman language. Centering her art around the experiences of Yanomami women, Yaira’s pieces confront the threats of sexual violence against women by illegal miners. Her art brings attention to the intertwined environmental and human costs of extraction.

By bringing Andujar’s photography into dialogue with Mokahesi’s and Yaira’s artworks, this exhibit challenges reductive climate narratives and foregrounds the Amazon as a lived, storied, and contested world. It imagines climate change not solely as an environmental crisis but also an ongoing struggle for human rights, cultural survival, and Indigenous sovereignty.

Claudia Andujar. Urihi-a. 1976

This photograph captured on infrared film is of a Yanomami home in the Amazon Rainforest. Its title “Urihi-a” in the Yanomaman language translates to “land-forest.” The Yanomami community understands the land-forest as a living being that is part of an interconnected cosmology of humans and non-humans, including animals, trees, and spirits. By highlighting a Yanomami home as the focal point of this photograph, Andujar refuses to portray the Amazon as merely a resource or a landscape. She orients viewers to understand the Amazon as more than a carbon sink or biodiversity inventory—underscoring the human life and various kinship relations present in the rainforest. In spotlighting the Yanomami perspective of the land-forest, Andujar honors Yanomami cosmology while also presenting an alternative framework for imagining the Amazon as a living, relational world.

Claudia Andujar. Guest decorated with vulture and hawk plumage for a feast. 1976

This infrared film photograph documents a reahu ceremony, which involves the invitation of guests and ceremonial exchanges. During a reahu ceremony, the Yanomami dance, feast, and breathe in Yakoana-tree powder, which is believed to be the food of the xapiri, ancestral spirits who protect Yanomami land. By using a multiple-exposure technique in this photograph, Andujar captures of the movement of dance, creates a dreamlike feeling, and alludes to the presence of spirits who the Yanomami shamans interact with. The multiplicity in this photograph represents the layers of the Yanomami cosmology that consist of reciprocal relations with the forest and other non-human beings. This cosmology counters environmental traditions that value the Amazon primarily for the ecosystem services it provides to humans.

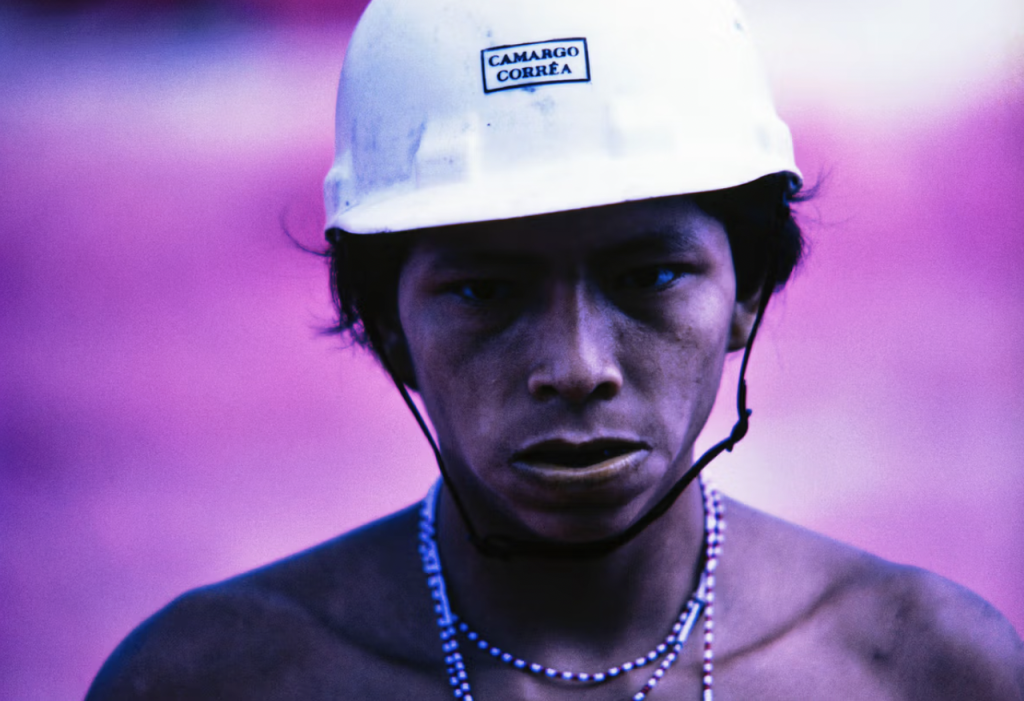

Claudia Andujar. Yanomami facing construction work on the Perimetral Norte highway, Catrimani, Roraima. 1975

In the 1970s, the Brazilian military dictatorship launched an Amazonian development plan, which included the construction of the Perimetral Norte (BR-210) highway that would deforest and cut through Yanomami territory. The act of building through Yanomami territory not only physically destroyed Yanomami lands, but it also symbolized government permission to occupy and extract. This photograph is of a Yanomami man wearing a construction helmet from Camargo Corrêa, one of the largest corporations involved in the highway construction. Andujar portrays the intrusion of the infrastructure that not only encroaches on the natural resources and biodiversity of the forest but also violently encroaches on indigenous lifeways and livelihoods. While the costs of development and deforestation in the Amazon are central topics in the climate discourse, the costs of community destruction are rarely discussed at the forefront of climate movements, and Andujar’s work challenges that precedent.

Claudia Andujar. Youth Wakatha u thëri. 1976

Throughout the 1970s, the Yanomami community faced outbreaks of measles, malaria, and other deadly diseases as outsiders encroached on Yanomami lands to construct roads and extract resources. This film photograph is of a young boy named Wakatha u thëri, a victim of measles, who was treated by shamans and Catholic missionary paramedics. In this quiet and intimate photograph, Andujar captures the human cost of the Amazon’s development. The Brazilian military dictatorship not only exploited natural resources in the name of economic development, but also neglected and killed human bodies in the process. This photograph serves both as a memorial for those whose lives were lost and a piece of evidence demonstrating how environmental disruption can become a public health crisis.

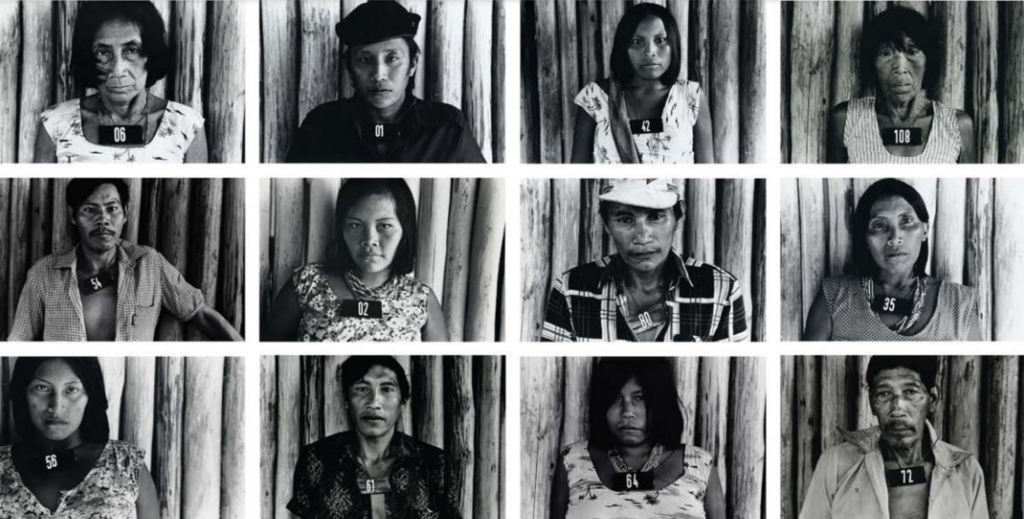

Claudia Andujar. Horizontal 2 (Village of Ericó) from the series Marcados. 1981-83

Yanomami people are reluctant to be photographed because of their belief that upon death, one should not leave any trace of themselves on Earth. Despite these beliefs, Andujar established a foundation of trust with the Yanomami community through her committed allyship and activism, and the Yanomami consented to being photographed in order to amplify their struggle for land demarcation. These black-and-white film portraits are a part of Andujar’s series Marcados, or marked. They were taken during a vaccination campaign led by Andujar to combat deadly epidemics transmitted through the forced contact that occured with highway construction and mining. From 1981 to 1984, Andujar photographed every person who was vaccinated with their identification number, each of which was associated with the individual’s medical charts, because the Yanomami did not reveal their names. In taking photographs that focus on the community members’ faces with their identification number, Andujar highlights the direct impacts of extraction to human health in the Amazon.

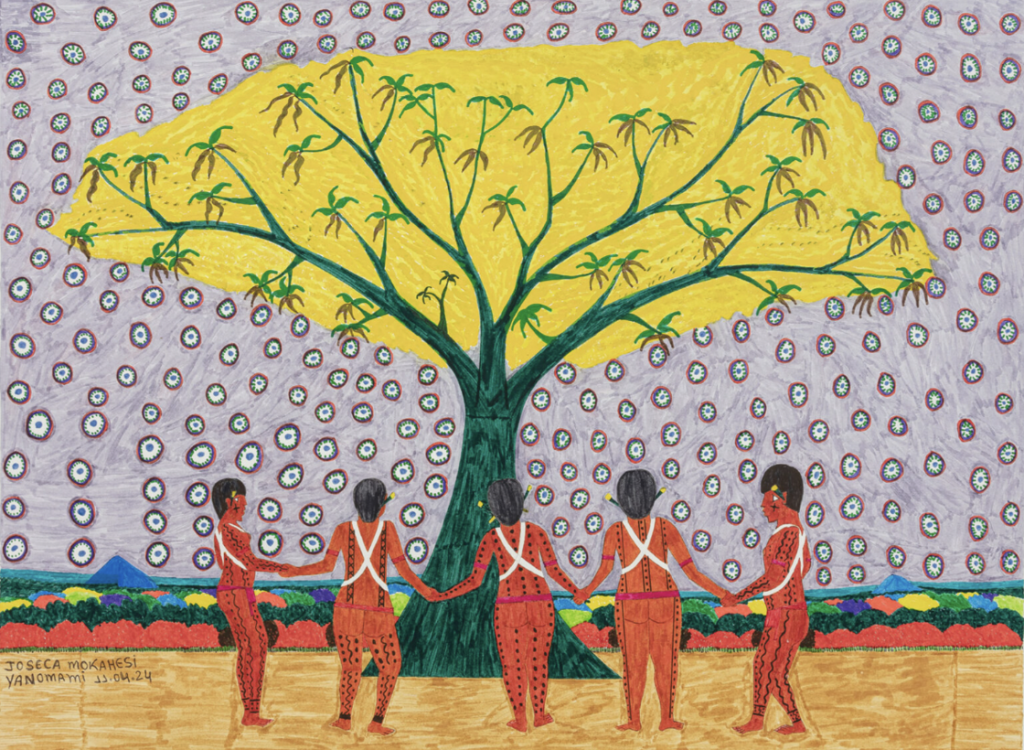

Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami. Drawing. 2024

Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami’s artwork focuses on translating the visions of Yanomami shamans into art. By aiming to make accessible what is only visible to shamans, Mokahesi uses his art as a communication strategy to connect with younger generations of Yanomami people as well as those outside of the Yanomami community. This felt-tip pen illustration depicts shamans inhaling dust from the Parara hi tree, which is believed to be the food of the spirits. Upon inhaling, shamans see a cosmological world in which all aspects of the forest, including spirits, are alive and continue to inhabit the forest. By communicating with the spirits, the shamans mediate relationships between the humans and nonhumans in the forest, and Mokahesi’s visual translation offers insight into how the Yanomami cosmology shapes and strengthens the community’s relentless defense of the forest.

Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami. Untitled. 2025

In Yanomami cosmology, the sky is not a backdrop but rather a structure that is upheld by the xapiri, or spirits. As shamans communicate with the xapiri, shamans ensure balance in the forest through relationships of reciprocity and stewardship. However, it is also possible for the sky to crack when this balance is disrupted, as depicted by Mokahesi’s acrylic painting. The painting depicts what would happen if the sky cracks: “all the animals will flee: the macaws, the parrots, the curassows, the tapis, the wild boards, the jaguars—they will all flee. Much rain will fall, and the winds will become very strong, and we will be devoured by the cannibalistic beings, the Ãopatari, who live in the underworld.” Despite this destruction described by Mokahesi, the painting itself does not evoke a sense of apocalyptic fear. Instead of underscoring fear, the purpose of this painting is to highlight the sacredness of the ecological, social, and spiritual balance maintained by the shamans. By emphasizing the vulnerability and fragility of this state of equilibrium, Joseca’s visual translation of Yanomami cosmology opens up discourse around relational repair and responsibility.

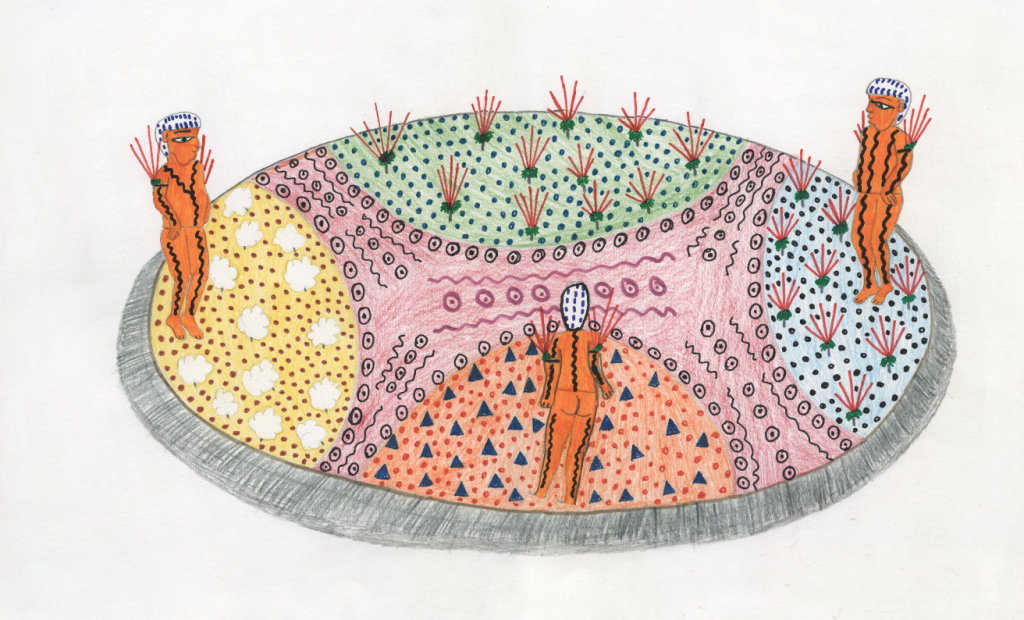

Joseca Mokahesi Yanomami. Spirits Cleanse the Rainforest. 2011.

This drawing captures the shamans’ vision of spirits who clean the land after it has been disrupted by miners. Even in the wake of the pollution and destruction brought by the mining industry, the spirits can restore the land with their armbands made with parrot feathers as seen on the top and right hand side, their white fur on the left hand side, and their ornaments made out of colorful birds at the bottom of the drawing. While calling out the violence of extraction and land invasions in the forest, Mokahesi’s drawing also visualizes a counter-narrative rooted in healing and restoration. He presents Yanomami cosmology as a form of resistance, refusing to accept extraction and continuing their defense of the forest. The forest is understood not just as a site of exploitation, but also as a site of complex relations that can be rehabilitated through ecological and spiritual balance.

Ehuana Yaira. Thuë Paximu, a woman in the forest adorned by ‘honey leaves.’ 2021.

One of very few Yanomami women who produce artwork on paper, Ehuana Yaira centers her artwork around the experience of Yanomami women. During her exhibition in New York City, The Yanomami Struggle, Yaira expressed, “I hope that spreading our pen strokes, our brush strokes, all over the world will, maybe, make people want to protect us.” By focusing this piece on a woman’s body in the rainforest, Yaira underscores the vulnerability of Yanomami people, and women in particular, who have not only endured violent treatment to their territories but also to their bodies by illegal miners. She emphasized that her hope is that “people from distant places will see my drawings…so that we can live well and in health” —demonstrating that crises of environmental extraction cannot be separated from crises of human rights violations.

Ehuana Yaira. Thuë Paximu, a woman in the forest adorned by ‘honey leaves.’ 2021.

Yanomami land has long faced exploitation at the hands of illegal miners, but during the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, illegal mining in demarcated Yanomami territory increased by over 300%. This escalation was fueled in large part by Bolsonaro’s dismantling of environmental laws, mining regulations, and organizations focusing on Indigenous land protection. This painting by Ehuana Yaira comments on the rise of sexual violence against Yanomami women associated with the illegal mining industry. In the painting, an illegal miner is pulling a Yanomami girl by her arms to dance with him. The river in the background is polluted, and alcohol bottles litter the ground. While illegal mining in the Amazon is most commonly thought of as a crisis of environmental exploitation, Yaira brings to the forefront the crisis of human exploitation, particularly in the form of sexual violence against women. During her exhibition in New York City, The Yanomami Struggle, Yaira shared her horror when she saw “Yanomami girls of 13 and 14 years old” exchanging “sex for rice, crackers, and pasta… in a brothel inside an illegal mining site.” While underscoring the vulnerability of women’s bodies that become the target of exploitation, Yaira’s piece interestingly portrays the woman as physically larger than the miner. This portrayal of physical dominance is perhaps an act of resistance against the violence and an act of defense of women’s bodies.