Ellen Harvey’s work invites us to reconsider the relationship between time, place, and memory. Known for her conceptual approach and meticulous technique, Harvey was born in the UK in 1967 and studied at Harvard University before attending the Whitney Independent Study Program. Her practice spans painting, installation, and site-specific projects, often interrogating the role of art in shaping cultural narratives. This exhibition, A Time and a Place: Ellen Harvey’s Monochrome Landscapes, explores how her black-and-white works—drawn from series including The Mermaid, The Impossibility of Capturing a Sunset, The Unloved, Double Forests, and selected pieces from The Disappointed Tourist—reframe our understanding of landscapes as both physical and temporal.

Harvey’s monochrome palette throughout these works is more than an aesthetic choice. By stripping away color, she removes the immediacy of the picturesque and instead emphasizes absence, memory, and fragility. These works depict locations, such as Key Food, Graham’s Rib Station, and the Chacaltaya Glacier, that are tied to specific moments and memories in time, yet exist beyond them. Some of these places no longer exist; others persist in changed forms. The black-and-white thread throughout the exhibit evokes a kind of archival photography, suggesting that what we see is already slipping into history. In doing so, Harvey asks us to confront the inevitability of change: cultural, infrastructural, and ecological.

One of the most poignant projects represented in this exhibition is The Disappointed Tourist. This ongoing series began with Harvey’s invitation during COVID for people to submit places they miss, including sites erased by time, disaster, or neglect. Harvey then paints these vanished locations in monochrome, granting them a second life as art. The works are deeply personal yet collectively resonant: a grocery store, a pier, a glacier. In this way, The Disappointed Tourist asks what it means to grieve for a place and why such grief matters in an era of accelerating environmental loss.

Climate change is often framed as a looming catastrophe, urgent and future-oriented. Harvey’s landscapes complicate this narrative by situating environmental loss within a continuum of time and place. Each image becomes a memorial, acknowledging that landscapes are never static. They evolve, erode, and vanish, sometimes gradually, sometimes abruptly. To mourn these transformations is not to indulge nostalgia but to cultivate empathy, which is a necessary step toward meaningful engagement with climate realities. Harvey’s work insists that we cannot separate time from geography. The ticking clock is embedded in the land.

The exhibition’s title, A Time and a Place, underscores this inseparability. Every location exists within a temporal frame, and every moment is shaped by its environment. Harvey’s monochrome landscapes make this visible, inviting viewers to pause and consider what it means to inhabit a world in flux. They remind us that preservation is not always possible, but remembrance is. In rendering these sites with care and precision, Harvey offers a quiet but urgent proposition: that empathy begins with attention, and attention begins with seeing.

The Mermaid: Two Incompatible Systems Intimately Linked

The Mermaid: Two Incompatible Systems Intimately Linked, Ellen Harvey, 2020. Acrylic and oil on 60 aluminum panels, each 40″ x 60″ (1.02 x 1.52 m). Overall height 10 ft (3.05 m). Overall width 100 ft (30. 48 m). Photography: Etienne Frossard.

Harvey’s monumental installation, The Mermaid, spans 100 feet of aluminum panels painted in oil and acrylic. The work was created for the lobby of the Miami Beach Convention Center, a site vulnerable to rising seas. It is based on a diagonal satellite view of Florida reaching from the Bay of Biscayne through the Everglades to Miami Beach and the Atlantic Ocean. Harvey writes that it is named after the half-human and half-fish mermaid because of the two landscapes lying side-by-side.

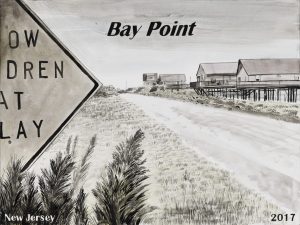

Bay Point

The Disappointed Tourist: Bay Point, Ellen Harvey, 2024. Oil and acrylic on Gessoboard, 18 x 24″ (46 x 61 cm). Photograph: Etienne Frossard.

Bay Point was a small town on the Delaware Bay, known for fishing and crabbing. “I grew up here. Blue Acres bought up the houses and we were forced to move. They demolished all the houses which was devastating. Now there are just poles and rubbish on the bay where homes used to be.” —Jerica H. Hurricane Sandy and other severe storms accelerated erosion and flooding, leading the state to buy out properties through its Blue Acres program. While intended to restore natural habitat, the buyouts erased homes and livelihoods in one of New Jersey’s poorest counties.

Graham’s Rib Station

The Disappointed Tourist: Graham’s Rib Station, Ellen Harvey, 2021. Oil and acrylic on Gessoboard, 18 x 24″ (46 x 61 cm). Photograph: Etienne Frossard.

Opened in 1932 by James and Zelma Graham on Route 66, Graham’s Rib Station became a refuge for Black travelers and soldiers during segregation. “Black soldiers stationed at Fort Leonard Wood… had to drive eighty miles to Graham’s Rib Station for food, fun and entertainment.” —Natasha L. The restaurant was unsegregated and included seven stone cabins, one of only two places in Springfield where African-American visitors could stay before desegregation. Graham’s hosted entertainers like Little Richard and Pearl Bailey, and Zelma ran the business until 1996, living to 106. The original building was demolished for the Chestnut Expressway; today, only a tourist cabin remains, repurposed as a storage shed.

Double Forest

Double Forest, Ellen Harvey, 2015-7. Oil and pressed glue ornaments on 12 framed Clayboard panels, each panel 24 x 36” (61 x 91.4 cm), together: (framed) 75 x 149” (1.9 x 3.78 m). Photography: Etienne Frossard.

Harvey’s Double Forest consists of twelve panels combining oil paint and pressed glue ornaments. It layers two forests like a reflection, creating a disorienting sense of repetition. Harvey describes it as “a meditation on the impossibility of returning to nature.” The decorative framing recalls historical interiors, suggesting that even our visions of wilderness are constructed. In black and white, the forest becomes something we idealize but cannot reclaim.

Key Food

The Disappointed Tourist: Key Food, Ellen Harvey, 2024. Oil and acrylic on Gessoboard, 18 x 24″ (46 x 61 cm). Photograph: Etienne Frossard.

“Walking into that grocery store was always strangely joyful… My sons grew up in those cheery aisles.” —Meredith M. Located at 120 Fifth Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and known for its spacious layout, familiar clerks, and retro soundtrack, Key Food offered a sense of community and comfort. When it closed in 2021 to make way for a 180-unit development, residents mourned the loss of affordable groceries. Harvey’s painting preserves a place remembered for its ordinary pleasures.

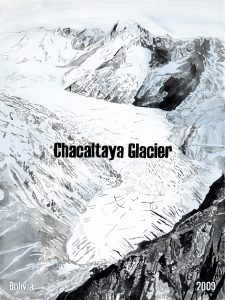

Chacaltaya Glacier

The Disappointed Tourist: Chacaltaya Glacier, Ellen Harvey, 2021. Oil and acrylic on Gessoboard, 24 x 18″ (61 x 46 cm). Photograph: Etienne Frossard.

Once home to the world’s highest ski resort, the Chacaltaya Glacier in Bolivia disappeared in 2009 (six years earlier than scientists predicted) due to accelerated climate change. It was part of the Tuni Condoriri system, which supplies water to El Alto and La Paz and feeds local hydroelectric plants. “My twin boys traveled there… to the place where the glacier had melted away to see the disused ski lift… So sad that climate change has taken effect so drastically fast.” —Alexandra S.

The Unloved

The Unloved, Ellen Harvey, 2014. One painting in four panels, oil on plywood, inlaid Plexiglas mirror, overall: 9’ 3/16” x 67’ 11½” (2.75 x 21.2m). Photography: Dominique Provost.

This four-panel painting focuses on Bruges, Belgium. The city is known for its famous medieval architecture, but maintains its lesser-known role as a modern container port. Harvey based the work on satellite images tracing the canal that links the historic city to the Port of Zeebrugge. All waterways are inlaid with mirror, creating a reflective surface that connects past and present. Bruges was once a major port before its canal silted up in the 16th century, leaving the city economically isolated. The new port, built in 1907, is now one of Europe’s largest. Originally part of a five-room installation at the Groeninge Museum, the painting now hangs in Bruges’ cruise terminal, providing a non-traditional depiction of the city.

Margate Pier

The Disappointed Tourist: Margate Pier, Ellen Harvey, 2021. Oil and acrylic on Gessoboard, 18 x 24″ (46 x 61 cm). Photograph: Etienne Frossard.

Margate Pier was designed by Eugenius Birch in 1856 and expanded between 1875 and 1878 with a pavilion. For decades, it was a focal point for seaside holidays, boat trips, and local life. “In August 1965 I went on a boat trip from Margate pier… I told my mates I had seen France.” —Anonymous. After years of neglect, the pier closed in 1976 for safety reasons and was destroyed by a storm on January 11, 1978.

Multifamiliar Juárez

The Disappointed Tourist: Multifamiliar Juárez, Ellen Harvey, 2025. Oil and acrylic on Gessoboard, 24 x 18” (61 x 45.7 cm). Photograph: Ellen Harvey

Designed by Mario Pani and decorated with mosaics by Carlos Mérida, Multifamiliar Juárez was a landmark of modernist architecture in Mexico City. It was demolished after the 1985 earthquake. “The building was irreparably damaged and torn down.” —Terence G. Harvey’s painting restores the building’s form, acknowledging its cultural significance and how quickly cities change through disaster.

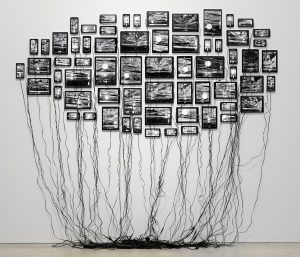

On the Impossibility of Capturing a Sunset

On the Impossibility of Capturing a Sunset (in Margate), Ellen Harvey, 2020. 65 Hand-engraved Plexiglas mirrors, Lumisheets, Plexiglas frames, electric cords, dimensions variable, here: 67 x 79” (1.7 x 2m). Photograph: Thierry Bal.

This installation uses 65 engraved Plexiglas mirrors and light panels to attempt what Harvey calls “the ultimate cliché of beauty”: a sunset. The mirrors scatter light into fractured reflections, making the image impossible to fix. Harvey’s work is less about success than about the act of trying: an acknowledgment that some experiences resist permanence.