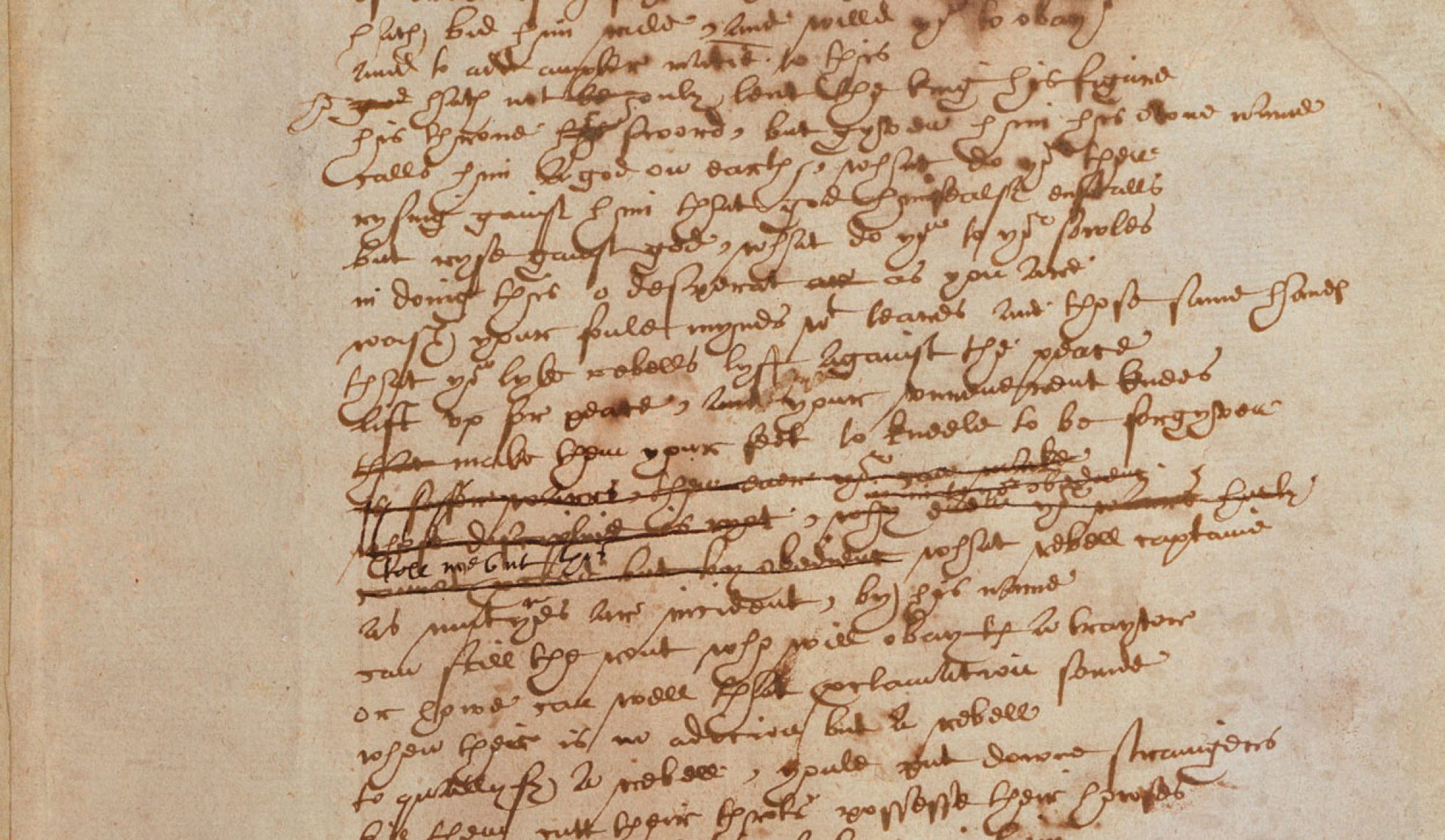

My chosen passage for emphasis in tomorrow’s class:

4.1.17–35

Princess

Nay, never paint me now.

Where fair is not, praise cannot mend the brow.

Here, good my glass, take this for telling true;

Fair payment for foul words is more than due.

Forester

Nothing but fair is that which you inherit.

Princess

See, see, my beauty will be saved by merit!

O heresy in fair, fit for these days!

A giving hand, though foul, shall have fair praise.

But come, the bow. Now mercy goes to kill,

And shooting well is then accounted ill.

Thus will I save my credit in the shoot:

Not wounding, pity would not let me do’t;

If wounding, then it was to show my skill,

That more for praise than purpose meant to kill.

And, out of question, so it is sometimes,

Glory grows guilty of detested crimes,

When, for fame’s sake, for praise, an outward part,

We bend to that the working of the heart;

As I for praise alone now seek to spill

The poor deer’s blood, that my heart means no ill.

What I like most about this passage is the density of thought in the Princess’s language. At first she ensnares the forester in a rhetorical trap by making him seem to deny that she is fair, then catching him out as if he were a flatterer. She posits a “heresy” in the word fair – the heresy being that “beauty,” like beatitude, can be apparently purchased through action and even direct payment. From this paradox of fair and foul, she proceeds to another in which mercy goes forth to kill. This paradox engenders yet another, expressed in economic terms of “account” and “credit”: if she shoots well, it might count against her. We return next to praise, the theme with which she began. She now notes that praise can motivate men and women to do evil. Having questioned first the ability of praise to render the foul fair, and now she seems to posit the ability of praise, or love thereof, to render the fair foul.

But this all smacks of interpretation on a higher level. To get back to our main task, I’m interested in how Shakespeare gets inside of language here. Last week I talked in class about his tendency to pull apart figures of speech, but perhaps another way Shakespeare creates the impression of thinking through language is when his characters create logical paradoxes through the manipulation of words, even stringing several of them together, as above. I am struck by how often in Shakespeare language is not just the medium of expression of thought, but very explicitly is the medium of thought itself. In other words, the Princess’s thoughts seem to proceed from language as much as her language seems to proceed from thought. I hope that makes some sense.

More prosaically, I’m a bit confused about how exactly to understand “for praise, an outward part, / we bend to that the working of the heart.” Is the “outward part” an appositive to “praise,” or is it the object of “bend”? She states a few lines later that her “heart means no ill” in the hunting – but if we bend to the working of the heart, does this not mean that we yield to it? Is it that the heart, while meaning no ill, desires praise, and that it is this positive desire, rather than a negative feeling of ill, that we respond to? What is the heart really doing here?

See you all soon.

Will Dingee