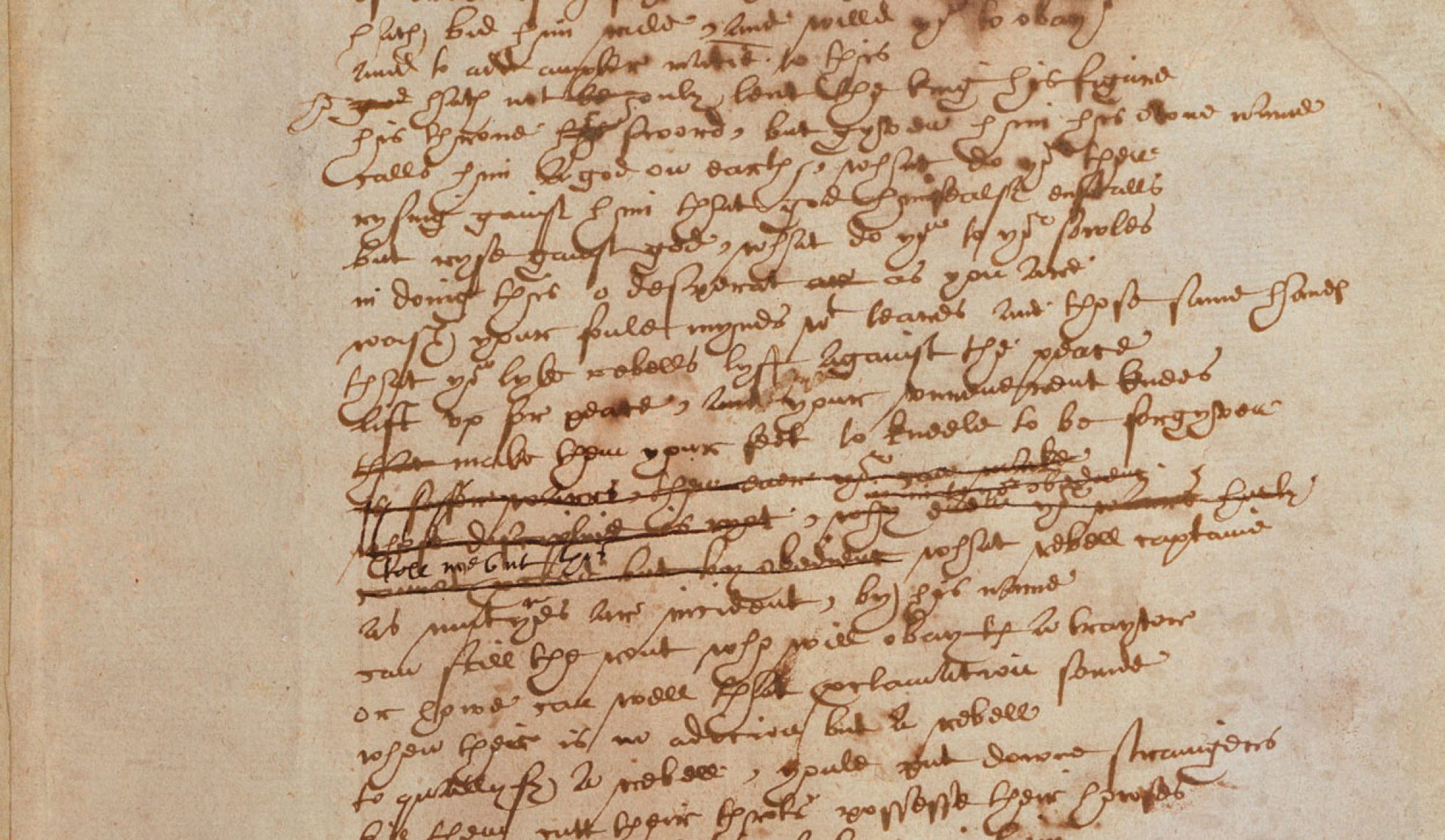

Leontes 1.2.281-293

Is whispering nothing?

Is leaning cheek to cheek? Is meeting noses?

Kissing with inside lip? Stopping the career

Of laughter with a sigh?—a note infallible

Of breaking honesty! Horsing foot on foot?

Skulking in corners? Wishing clocks more swift?

Hours minutes? Noon midnight? And all eyes

Blind with the pen and web but theirs, theirs only,

That would unseen be wicked? Is this nothing?

Why then the world and all that’s in’t is nothing,

The covering sky is nothing, Bohemia nothing,

My wife is nothing, nor nothing have these nothings

If this be nothing.

Much of The Winter’s Tale coasts along at a sort of midrange—characters saying what they need to say, with the appropriate degree of anger or love, in loose (rather, jam-packed) iambic pentameter, as all sorts of horrible or baffling things happen onstage (cast the baby into the desert! let’s see Antigonus shredded by a bear!). There are exceptions, though, and we might see occupying two opposite stylistic poles 1) the moments, longer than moments, when speech becomes mostly a vehicle for explicit narration and 2) the most violently impassioned utterances, when speech has the effect not of advancing narration but making itself the main event.

Into the former category I put the couplets by Time. Though they’re hardly unskilled (and are skillfully enjambed), the grammar is rather stilted, the feminine rhymes lilt, and a few of the rhyme pairs are near-howlers (“Florizel” and “well”…). If time’s triumph is in the plot, it’s not in the verse. I also put in this category the dialogue with the (completely interchangeable) gentlemen in 5.2, who go on at length in polite prose about something we could get the important details from in a few lines. What’s Shakespeare up to here?

At the opposite pole I put some of Leontes’ speeches in the first half of the play. 1.2.177-205 and 1.2.281-293 (above) are particularly remarkable, the first for its interinvolved metaphors, and the second for its rhythms. Of the latter, we see in its first few lines that the questions have an energy all their own: first just inching past the endstop with an extra unstressed syllable (“nothing,” “noses,” “career”), then breaking it with hard enjambment (“stopping the career / Of laughter” “a note infallible / Of breaking honesty). As the momentum builds, the grammatical elisions stack up. First we have understand that “Is ___ nothing” remains implied. Then “wishing” is elided too. And we never even get the necessary “be” verb that should be within the “wishing” questions (i.e. ‘is wishing clocks were more swift nothing?’ hours were minutes? Noon were midnight?’). And how do we scan “Hours minutes? Noon midnight” anyway? Leontes lops off more grammar and stretches the meter to a breaking point as his questions heap up. It’s an electrifying utterance.

I think for all the stress Shakespeare puts on the line in this play, though, it’s important not to say that the line no longer matters. We see in this very speech how the line can contribute even to a frantic energy; it’s not always just a calming balm or restricting force. At the end of the speech, Shakespeare plots first one “nothing” in the lines, then two, then three; the use of the line becomes a way to measure (or just feel) the intensity of repetitions becoming more frequent. And he uses the end of the line four times in a row to really ring out the “nothing,” so that it bangs like a drum punctuating each line end while the line itself correspondingly gives the performer the chance to sound out the “nothing” even more.

-Scott