Cornwall: Why art thou angry?

Kent: That such a slave as this should wear a sword

Who wears no honesty. Such smiling rogues as these

Like rats oft bite the holy cords a-twain,

Which are t’intrance t’unloose; smooth every passion

That in the natures of their lords rebel,

Being oil to fire, snow to the colder moods,

Revenge, affirm, and turn their halcyon beaks

With every gall and vary of their masters,

Knowing naught, like dogs, but following.

A plague upon your epileptic visage!

Smile you my speeches as I were a fool?

Goose, if I had you upon Sarum Plain,

I’d drive ye cackling home to Camelot.

Cornwall: What, art thou mad, old fellow?

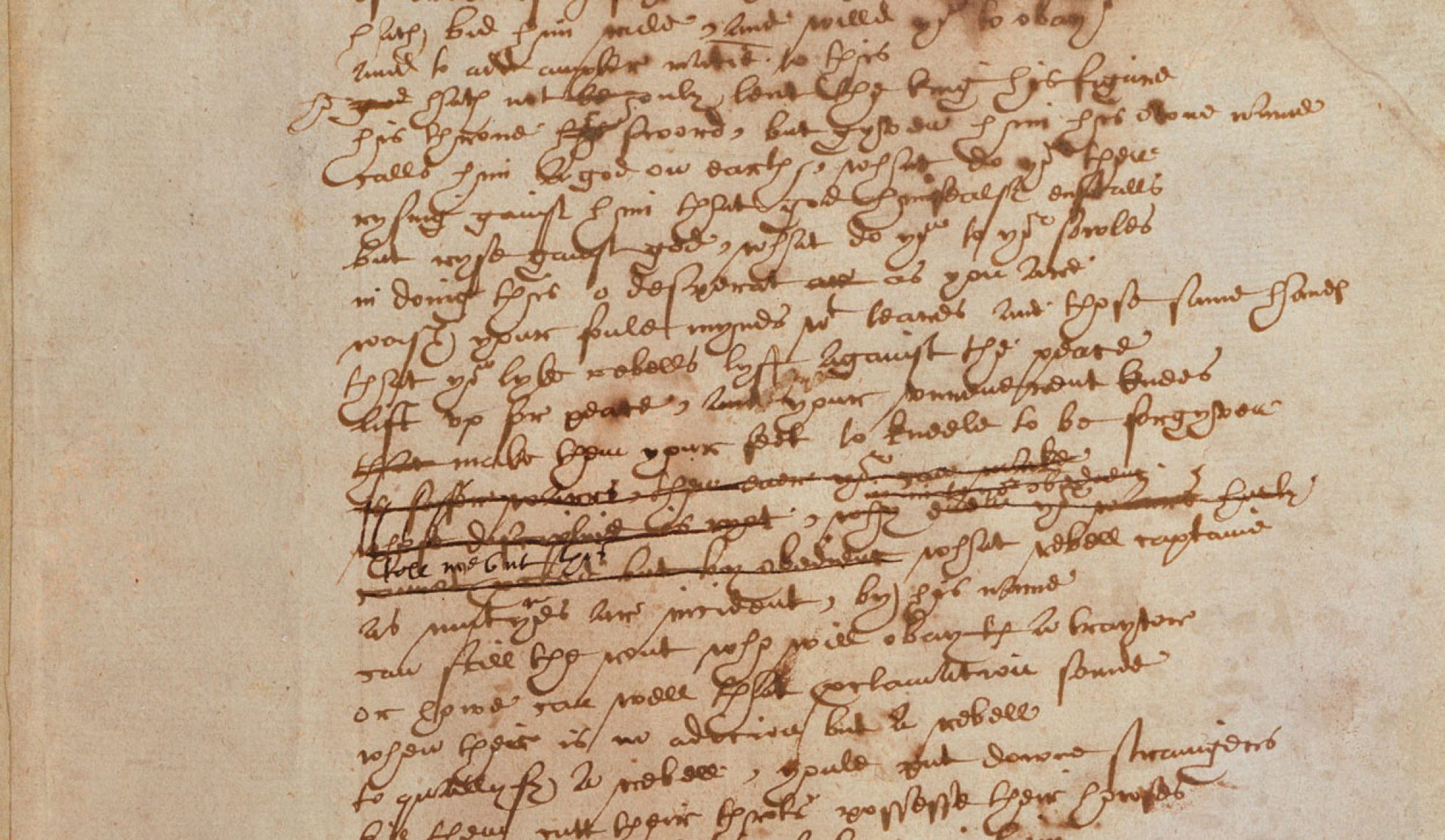

I’m interested in this moment as one in which communication seems to break down entirely, in part because of an excess of language, not a lack of it. Kent’s speech here embodies excess to a tee: it describes an excess of servitude (“oil to fire, snow to the colder moods”), there is an excessive amount of metaphor and figuration, and as a (non) answer to Cornwall’s question, the speech is in itself excessive. What I find particularly skillful—and what I think has bearing on the play as a whole—is the foundation of “naught” upon which this excess is built. Not only does this 13 line speech fail to answer Cornwall’s question, there is also (at least in the eyes of everyone else on stage) no apparent reason for it, and its string of metaphors builds into one involving dogs which both know “naught” and follow nothing, syntactically as well as metaphorically. I like the use of this in a play that in so many ways has “nothing” at its center but an old man’s folly, sparking an excessive chain of events.

What’s more, and what’s particularly pertinent to this week’s theme, this passage deals with multiple transformations of the human body into animal form. Is this merely a complement to “poor, bare, forked animal” that seems to me to be the center of this play—“unaccommodated man”? Or is there something more organized or developmental to this progression of curious and consistent animal metaphor? Each featured animal has a specific physical or verbal trait assigned to it (rats biting, birds with beaks, dogs following); there is an order and symmetry to the animal-metaphors in a rant that is otherwise made up of unstable outbursts. What’s more, this passage suggests itself as an extreme counterpart to Edgar’s more famous and more subdued speech in Act 2.3, in which he “take(s) the basest and most poorest shape / That ever penury in contempt of man / Brought near to beast.” We also have another strangely symmetrical and specific animal-laden speech by the fool at 2.4.6, commenting on Kent’s position in the stocks as a result of the encounter in question.

I’m not sure what to make of all of this beastly figurative transformation, except that I find it appropriate in this moment where people begin to thoroughly misunderstand each other, and particularly apt in a play in which civilization all but breaks down. The fact that Cornwall’s questions develop only from “why art thou angry” to “art thou mad”—two simple lines to Kent’s 13—helped me to think about the exchange that follows this speech in terms of this week’s exercise, as well. I decided to think about how Kent and his interlocutors might abandon communication altogether and staged the passage following this one as a fight.