A quick FYI: My post is going to overlap ever-so-slightly with Jeewon’s. However, I’ll be looking at mostly different passages and working through different ideas, so hopefully my selection won’t ruffle too many feathers!

I’m thinking about Fowler’s definition of a character as a social person, one whose construction depends “not only upon their contexts of topoi and institutions, but also upon their positions in networks of social relationships” (14). Fowler’s argument suggests that an analysis of character must emerge, not just through the character’s own words, but through a complete mapping of all the contexts in which that character appears. In the first two scenes of the play, Prince Henry is revealed to the audience through a series of lenses, refracted through multiple contexts. So, let’s consider the intersections between character, context, and language at three points: when King Henry first mentions his son at the end of the first scene, when Hal and Falstaff pun and joke at the beginning of 1.2, and when Hal delivers his soliloquy at the end of 1.2.

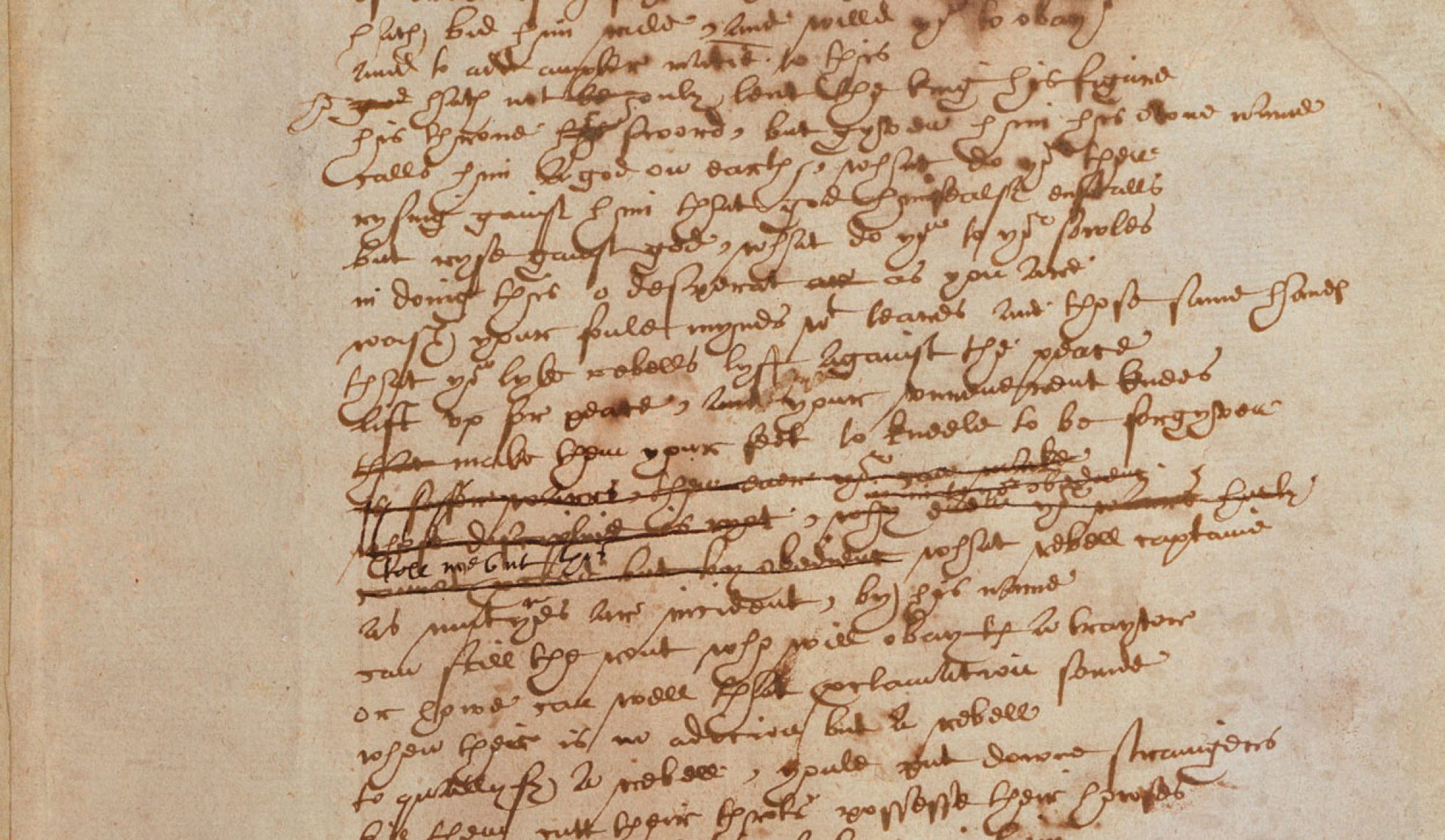

We first hear about Hal before we meet him, during the King’s complaint in 1.1, 77-94:

KING HENRY

Yea, there thou mak’st me sad, and mak’st me sin

In envy that my lord Northumberland

Should be the father to so blest a son–

A son who is the theme of honor’s tongue,

Amongst a grove the very straightest plant,

Who is sweet Fortune’s minion and her pride–

Whilst I, by looking on the praise of him,

See riot and dishonor stain the brow

Of my young Harry. O that it could be proved

That some night-tripping fairy had exchanged

In cradle-clothes our children where they lay,

And called mine Percy, his Plantagenet!

Then would I have his Harry, and he mine.

But let him from my thoughts. What think you, coz,

Of this young Percy’s pride? The prisoners

Which he in this adventure hath surprised

To his own use he keeps, and sends me word

I shall have none but Mordake, Earl of Fife.

- In the King’s speech, I notice his use of three consecutive figures to illustrate Hotspur, the son he wishes he had, a son who is “the theme of honor’s tongue,” “the straightest plant” in a grove, and “sweet Fortune’s minion.” The syntax lines up neatly in accordance with the line, with each figure fitting into one end-stopped line.

- Now, let’s compare the language used to imagine an ideal son with the language of the son himself, Hal. Notice the way Hal’s metaphors pile up in his banter with Falstaff at the opening of 1.2, 1-11.

FALSTAFF

Now, Hal, what time of day is it, lad?

PRINCE HENRY

Thou art so fat-witted with drinking of old sack, and unbuttoning thee after supper, and sleeping upon benches after noon, that thou hast forgotten to demand that truly which thou wouldst truly know. What a devil hast thou to do with the time of day? Unless hours were cups of sack, and minutes capons, and clocks the tongues of bawds, and dials the signs of leaping-houses, and the blessed sun himself a fair hot wench in flame-coloured taffeta, I see no reason why thou shouldst be so superfluous to demand the time of the day.

- Think about what the audience has just heard: Only a minute before, they listened to the King lament “in envy that my Northumberland / should be the father to so blest a son.” Now, they hear “the blessed sun” compared to “a fair hot wench in flame-coloured taffeta”! In this case, the wordplay–and the sense that Hal definitely isn’t living up to his father’s expectations–moves across scenes, not just within them.

- What’s more, consider the way in which metaphors accumulate here. The connections are rapid-fire, spilling across these lines of prose: cups → sack, minutes → capons, clocks → tongues, dials → signs, sun → wench. There’s a messiness and an excess here, so different from the King’s three neat metaphors that we observed earlier.

- Finally, let’s turn to Hal’s soliloquy at the end of this scene. This is where we first see the “other side” to his character. It’s notable, of course, that he switches from prose to poetry and that’s he’s alone in the tavern. But, I’m also interested in his use of figuration and the ways in which he’s able to sustain a conceit over the course of several lines. Here’s the speech in 1.2, 183-205, typed out a second time:

PRINCE HENRY

I know you all, and will awhile uphold

The unyoked humour of your idleness.

Yet herein will I imitate the sun,

Who doth permit the base contagious clouds

To smother up his beauty from the world,

That, when he please again to be himself,

Being wanted he may be more wondered at

By breaking through the foul and ugly mists

Of vapours that did seem to strangle him.

If all the year were playing holidays,

To sport would be as tedious as to work;

But when they seldom come, they wished-for come,

And nothing pleaseth but rare accidents.

So when this loose behavior I throw off

And pay the debt I never promised,

By how much better than my word I am,

By so much shall I falsify men’s hopes;

And like bright metal on a sullen ground,

My reformation, glitt’ring o’er my fault,

Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes

Than that which hath no foil to set it off.

I’ll so offend to make offence a skill,

Redeeming time when men think least I will.

- I’ve marked in bold two of the main figures in this speech: when Hal compares himself to the sun and when he then compares his “reformation” to “bright metal on a sullen ground.” What interests me about these moments is that fact that Hal sustains these comparisons over the course of multiple lines. He proves himself able to develop an abstract thought at length, a skill that’s very different from the rapid-fire punning that opens the scene. In this way, the transformation in language mirrors the transformation of character, a third lens through which we might begin to assemble Hal’s character.

Looking forward to thinking through character with all of you tomorrow!

Jackie