KENT

Here is the place, my lord: good my lord, enter;

The tyranny of the open night’s too rough

For nature to endure. Storm still.

LEAR Let me alone.

KENT

Good my lord, enter here.

LEAR Wilt break my heart?

KENT

I had rather break mine own. Good my lord, enter.

LEAR

Thou think’st ’tis much that this contentious storm

Invades us to the skin: so ’tis to thee.

But where the greater malady is fixed,

The lesser is scarce felt. Thou’dst shun a bear,

But if thy flight lay toward the roaring sea,

Thou’dst meet the bear i’ th’ mouth. When the mind’s free,

The body’s delicate: this tempest in my mind

Doth from my senses take all feeling else,

Save what beats there, filial ingratitude.

Is it not as this mouth should tear this hand

For lifting food to’t? But I will punish home;

No, I will weep no more. In such a night

To shut me out? Pour on, I will endure.

In such a night as this? O Regan, Goneril,

Your old, kind father, whose frank heart gave you all –

O, that way madness lies, let me shun that;

No more of that.

KENT Good my lord, enter here.

LEAR

Prithee, go in thyself. Seek thine own ease.

This tempest will not give me leave to ponder

On things would hurt me more. But I’ll go in;

[To the Fool.] In boy, go first. You houseless poverty –

Nay, get thee in. I’ll pray, and then I’ll sleep. Fool exits.

Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this. Take physic, pomp,

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou may’st shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just.

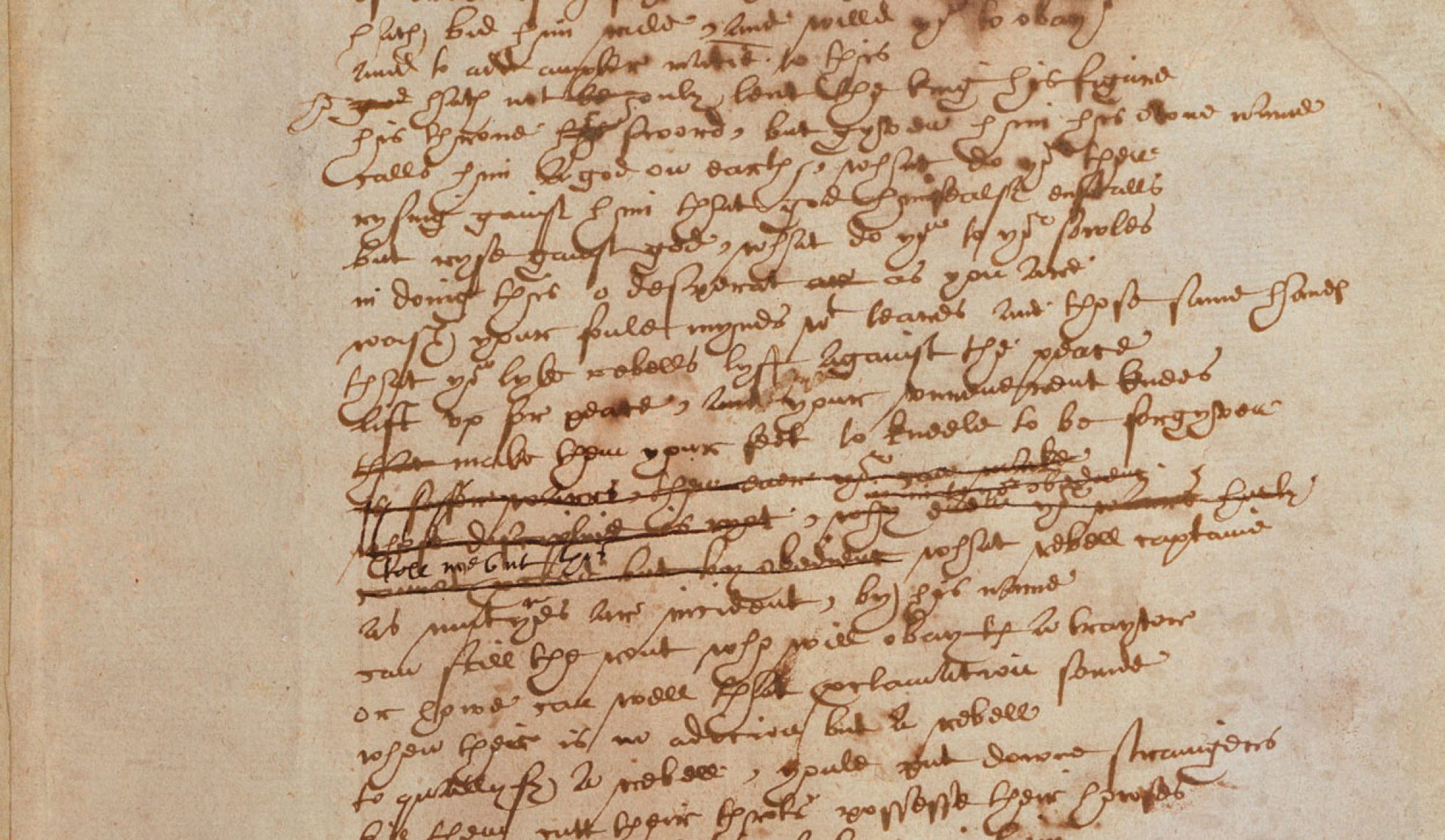

I include Kent’s lines to Lear at the beginning of 3.4 for context, but I’d like to track the psychological distance covered between – and within – Lear’s first two speeches in the scene. I was impressed by the number of ramifications generated from the basic source of conflict or tension here: Kent’s struggle to lead Lear into shelter. Lear’s monologues are, functionally, justifications for resisting Kent’s efforts, and the first speech in fact identifies Kent as its audience through direct address; when Lear invents a rather spontaneous analogy for preferring the lesser of two proverbial evils, we can assume that he is still addressing Kent. Thereafter, though, “the tempest in my mind” appears to coopt the properly dialogic capacity of Lear’s speech and Lear begins to refer to himself in posing a series of self-directed challenges or internal struggles. Lear can’t come to grips with Regan’s and Goneril’s ingratitude, so he vacillates – between restraining and venting emotion, between expressing indignation and disbelief, and, into the second speech, between following Kent and braving the storm. The progress of the action here depends on Lear’s remaining undecided (and so, delivering his lines outdoors), whereas the characterological effect of his insecurity might serve to underscore his frailty, or foreshadow his madness, or demonstrate the extent of his grief, or perform all three functions at once: the point being, Lear does not know his mind, and he speaks and acts accordingly.

But one transition over the course of this passage struck me above all, which involves the extension of sympathy or feeling (such a crucial term in the play) Lear undergoes between his first and second monologues. “[T]his tempest in my mind / Doth from my senses take all feeling else, / Save what beats there, filial ingratitude,” Lear initially declares, after explaining that, “where the greater [mental/psychological/spiritual/emotional] malady is fixed, / The lesser [physical] is scarce felt.” Lear’s frame of reference at the outset of the scene is only as wide as his personal experience, despite the amplification achieved by setting his domestic, paternal afflictions against his physical suffering during the storm. Lear’s admission to feeling nothing but the sting of “filial ingratitude” attests to a kind of sensorial obstruction that apparently deteriorates by the time Lear is incapable of even registering his daughters’ cruelty (“In such a night / To shut me out? Pour on, I will endure. / In such a night as this?). This suggests both an imaginative sterility* and a degree of self-concern that Lear reverses in his apostrophic second speech to an altogether different, drastically expanded audience. Lear’s unexpected invocation of his public, political sphere of influence – his reign, no more successful than his fatherhood – introduces another dimension to the representation of irresponsible authority in the play and adds depth and complexity to the humanity personified in the figure of Lear. We’ll talk about feeling in terms of identification or sympathy and in connection with seeing, I hope (recall Gloucester at 4.1.70-74, especially), but we can also discuss the status of obligation and loyalty, and even justice, as considered here. And might we push as far as love?

Jessica

*I make this observation about Lear’s circumscribed point of view without any sound explanation for the fanciful bear analogy. Speculations are welcome.