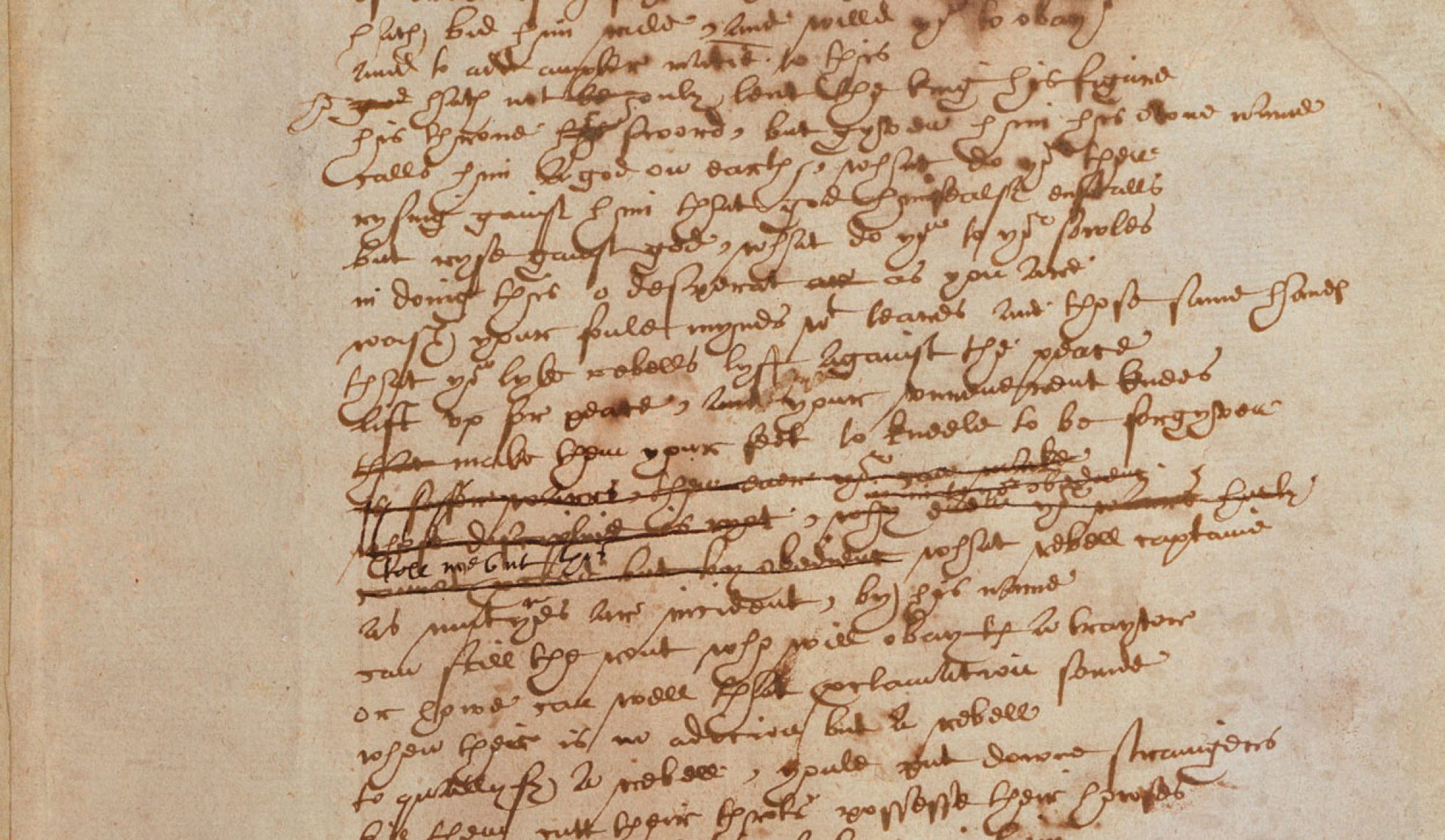

(I did my best to make the Folger online text of this passage consistent with our Oxford version, but please forgive any discrepancies in formatting, punctuation, etc.)

Enter Cassio

RODERIGO

I know his gait, ’tis he! (Attacking Cassio) Villain, thou diest!

CASSIO

That thrust had been mine enemy indeed

But that my coat is better than thou know’st—

I will make proof of thine.

He wounds Roderigo

RODERIGO O, I am slain!

Iago wounds Cassio in the leg from behind, and exit

CASSIO

I am maimed forever! Help, ho! Murder, murder!

Enter Othello

OTHELLO

The voice of Cassio! Iago keeps his word.

RODERIGO O, villain that I am!

OTHELLO, (aside) It is even so.

CASSIO O, help ho! Light! A surgeon!

OTHELLO, (aside)

’Tis he! O brave Iago, honest and just,

That hast such noble sense of thy friend’s wrong!

Thou teachest me.—Minion, your dear lies dead,

And your unblest fate hies. Strumpet, I come.

Forth of my heart those charms, thine eyes, are blotted.

Thy bed, lust-stained, shall with lust’s blood be spotted.

Exit

Enter Lodovico and Gratiano

CASSIO

What ho! No watch? No passage? Murder, murder!

GRATIANO

’Tis some mischance; the voice is very direful.

CASSIO O, help!

LODOVICO Hark!

RODERIGO O wretched villain!

LODOVICO

Two or three groan. It is a heavy night;

These may be counterfeits: let’s think’t unsafe

To come in to the cry without more help.

RODERIGO

Nobody come? Then shall I bleed to death.

Enter Iago with a light and his sword drawn

LODOVICO Hark!

GRATIANO

Here’s one comes in his shirt, with light and weapons.

IAGO

Who’s there? Whose noise is this that cries on murder?

LODOVICO

We do not know.

IAGO Do not you hear a cry?

CASSIO

Here, here! For heaven’s sake, help me!

IAGO What’s the matter?

GRATIANO

This is Othello’s ensign, as I take it.

LODOVICO

The same indeed, a very valiant fellow.

IAGO

What are you here that cry so grievously?

CASSIO

Iago? O, I am spoiled, undone by villains—

Give me some help!

IAGO

O me, lieutenant! What villains have done this?

CASSIO

I think that one of them is hereabout

And cannot make away.

IAGO O treacherous villains!

[To Lodovico and Gratiano]

What are you there? Come in, and give some help.

RODERIGO

O, help me there!

CASSIO

That’s one of them.

IAGO O murd’rous slave!

O villain!

He stabs Roderigo

RODERIGO

O damned Iago! O inhuman dog!

[Roderigo groans]

IAGO

Kill men i’ th’ dark?—Where be these bloody thieves?

How silent is this town! Ho, murder, murder!

(To Lodovico and Gratiano)

What may you be? Are you of good or evil?

LODOVICO

As you shall prove us, praise us.

IAGO Signor Lodovico?

LODOVICO He, sir.

IAGO

I cry you mercy—here’s Cassio hurt by villains.

GRATIANO Cassio?

IAGO

How is ’t, brother?

CASSIO My leg is cut in two.

IAGO Marry, heaven forbid!

Light, gentlemen: I’ll bind it with my shirt.

Enter Bianca

BIANCA

What is the matter, ho? Who is ’t that cried?

IAGO

Who is ’t that cried?

BIANCA O, my dear Cassio,

My sweet Cassio, O Cassio, Cassio, Cassio!

IAGO

O notable strumpet! Cassio, may you suspect

Who they should be, that have thus mangled you?

CASSIO No.

GRATIANO

I am sorry to find you thus; I have been to seek you.

IAGO

Lend me a garter. So.

He binds Cassio’s leg

O for a chair to bear him easily hence!

BIANCA

Alas, he faints! O, Cassio, Cassio, Cassio!

IAGO

Gentlemen all, I do suspect this trash

To be a party in this injury.

Patience awhile, good Cassio. (To Lodovico and Gratiano) Come, come;

Lend me a light: (Going to Roderigo) know we this face, or no?

Alas, my friend and my dear countryman,

Roderigo! No? —Yes, sure!—O heaven, Roderigo!

GRATIANO What, of Venice?

IAGO Even he, sir—did you know him?

GRATIANO Know him? Ay.

IAGO

Signior Gratiano? I cry your gentle pardon:

These bloody accidents must excuse my manners

That so neglected you.

GRATIANO I am glad to see you.

IAGO

How do you, Cassio? [Calling] O, a chair, a chair!

GRATIANO Roderigo?

IAGO

He, he, ’tis he.

Enter attendants with a chair

O, that’s well said—the chair!

Some good man bear him carefully from hence,

I’ll fetch the General’s surgeon. (To Bianca) For you, mistress,

Save you your labor.—He that lies slain here, Cassio,

Was my dear friend. What malice was between you?

CASSIO

None in the world; nor do I know the man.

IAGO (to Bianca)

What, look you pale? (To attendants) O, bear him out o’ th’ air!

(To Gratiano and Lodovico)

Stay you, good gentlemen.

Exeunt attendants with Cassio in the chair and the body of Roderigo

(To Bianca) Look you pale, mistress?

(To Lodovico and Gratiano) Do you perceive the gastness of her eye?

(To Bianca) Nay, if you stare, we shall hear more anon.

(To Lodovico and Gratiano) Behold her well. I pray you, look upon her:

Do you see, gentlemen? Nay, guiltiness

Will speak though tongues were out of use.

Enter Emilia

This was actually my first time reading Othello, and I’m afraid I might have missed something because I found it kind of…funny. There were moments when I could have laughed at the turn language? – speech, certainly, was taking, moments when characters’ verbal faculties seemed to melt down in ways it was difficult for me to imagine. There was Othello’s swoon, for one, though I could conceive of that in terms of pure emotional overdrive – but what about all the parroting, the lapses into mimicry on Iago’s, Emilia’s, Desdemona’s, Roderigo’s respective parts, often in conversation among themselves and/or with (especially) Othello? There’s Iago goading Roderigo on to “put money in thy purse” in 1.3; there’s Othello obsessing over Desdemona’s handkerchief in 3.4; there’s Emilia repeating after Othello like another broken record player in 5.2. And what about the as-yet-inconceivable (to me at least, and I haven’t yet seen any productions of the play) beelines performed in act as well as in speech by a cluster of characters at the start of Act 5?

It’s this episode that I’d like to highlight for emphasis this week, if mainly to get a clearer grasp of just exactly what is happening – and why – among the disoriented company on stage. I was struck by the number recycled words and phrases, for one, but even more so by their apparent extraneousness, hollowness, and accordingly by an impression of inertia paradoxical for such a kinetic scene. The more closely I followed these sequences of verbal echoes, the longer my passage became; I could reasonably have excerpted all of 5.1 – but that would have been more unreasonable than the helping I’ve provided above.

As you (re)read, note how many expressions bleed into multiple lines that, sometimes, fall at decent intervals from one another and/or carry into different characters’ speech. Does the repetition evacuate words of meaning here, or serve to escalate the tension of the drama? On the former count, note too the frequency of what Dolar would call ““prelinguistic’ phenomena” – all the “O”s, for instance, but also the groaning in the stage directions. One question I asked myself upon finishing Othello was: How does the play register doubt, insecurity, or confusion? Is this a scene that might exemplify the answer?

To be honest, I couldn’t hear this scene very well (unless it were as poorly-scripted melodrama!), but I could visualize it being pitch dark on the stage: Roderigo explicitly identifies Cassio by his gait, Iago enters bearing a torch, and the action depends on the lack of facial recognition, which the dialogue underscores by means of consistently questioned identities. Even so, I found the scene a little implausibly long, such that all the commotion lent itself to a kind of inertia, as I mentioned above. It wasn’t by accident that I also ventured to call the language here surprisingly hollow. If we imagine the characters acting upon strictly or predominately acoustic cues – engaging in a form of echolocation, as it were, especially with Cassio and Roderigo fixed in position on stage – could it follow that words are just sounds here? Or do the stakes of the action enhance the significance of the language?

A comment in closing on a pattern I noticed throughout the play and will refer to as split or layered speech. Othello’s “letter-reading” in 4.1, like Desdemona’s song in 5.2, provides a great example of speech that takes multiple addressees or demonstrates divided attention, and Iago’s lines at the end of the segment I’ve quoted work the same way. This effect might be extended to occasions of suspended syntax or interrupted utterance (also asides), which suggest parallel trains of thought and/or expression and which occur rather often in Othello. Did you find this trend meaningfully pronounced in this of the plays we’ve read so far? And if yes, perhaps thinking along the lines I’ve sketched above, how so?

Jessica