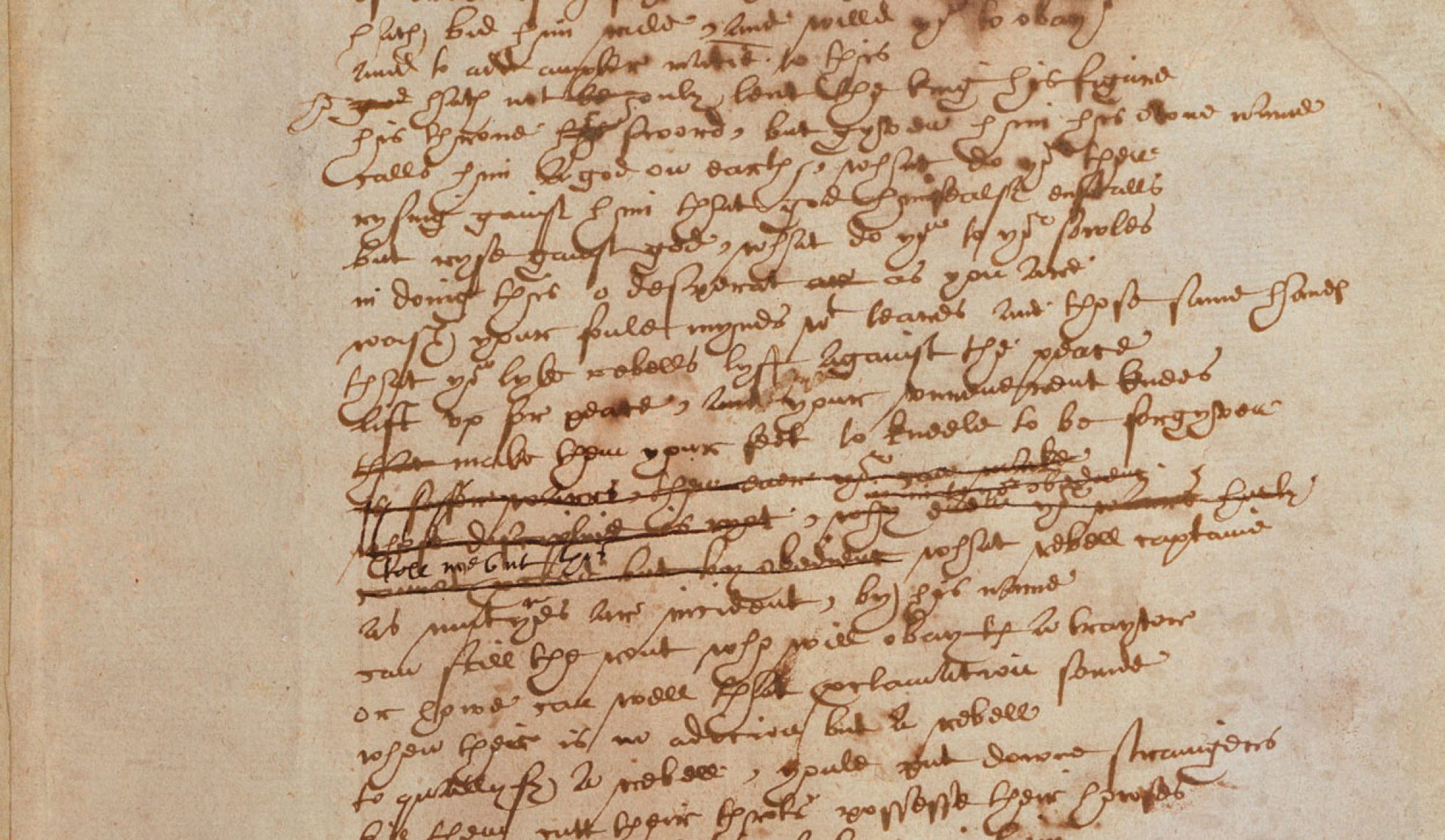

This passage is from 3.2.148-220 (I should note, I am working from the Arden Shakespeare edition of Hamlet, so there may be some variation, apologies!)

Player King:

Full thirty times hath Phoebus’s cart gone round

Neptune’s salt wash and Tellus’ orbed ground

And thirty dozen moons with borrowed sheen

About the world have times twelve thirties been

Since love our hearts and Hymen did our hands

Unite commutual in most sacred bands.

Player Queen

So many journeys may the sun and moon

Make us again count o’er ere love be done.

But woe is me, you are sick of late,

So far from cheer and from our former state,

That I distrust you. Yet, though I distrust,

Discomfort you, my lord, it nothing must.

For women fear too much, even as they love,

And women’s fear and love hold quantity—

Either none, in neither aught, or in extremity.

Now what my love is proof hath made you know

And, as my love is sized, my fear is so.

Where love is great, the littlest doubts are fear,

Where little fears grow great, great love grows there.

Player King

Faith, I must leave thee, love, and shortly too,

My operant powers their functions leave to do,

And thou shalt live in this fair world behind

Honoured, beloved, and haply one as kind

For husband shalt thou—

Player Queen

O, confound the rest!

Such love must needs be treason in my breast.

In second husband let me be accurst:

None wed the second but who killed the first.

Hamlet

That’s wormwood!

Player Queen

The instances that second marriage move

Are base respects of thrift, but none of love.

A second time I kill my husband dead

When second husband kisses me in bed.

Player King

I do believe you think what now you speak.

But what we do determine oft we break.

Purpose is but the slave to memory,

Of violent birth but poor validity,

Which now like fruit unripe sticks on the tree

But fall unshaken when they mellow be.

Most necessary ‘tis that we forget

To pay ourselves in passion we propose,

The passion ending doth the purpose lose.

The violence of either grief or joy

Their own enactures with themselves destroy.

Where joy most revels grief doth most lament,

Grief joys, joy grieves, on slender accident.

This world is not for aye, nor ‘tis not strange

That even our loves should with our fortunes change,

For ‘tis a question left us yet to prove

Whether Love lead Fortune or else Fortune Love.

The great man down, you mark his favourite flies,

The poor advanced makes friends of enemies,

And hitherto doth Love on Fortune tend,

For who not needs shall never lack a friend,

And who in want a hollow friend doth try

Directly seaons him his enemy.

But orderly to end where I begun,

Our wills and fates do so countrary run

That our devices still are overthrown.

Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own:

So think thou wilt no second husband wed

But die thy thoughts when thy first lord is dead.

I’ve chosen this passage from the play within a play in Act 3 because the play, particularly in who it is designed to address, is a particularly productive site for thinking about “time” in Hamlet. The play, The Murder of Gonzago, is of course Hamlet’s way of gauging whether what the ghost has told him of his father’s murder is true; by observing how his uncle and mother (the King and Queen) respond he hopes to judge their guilt or innocence in the affair. At the macro-level, the play stages the question of whether these “ghosts” of the past are still visibly manifest—is the play out of the times of Claudius’ court, or, is it very much in time?

The epic opening of the performance, given in the Player King’s classical allusion to “Phoebus,” “Neptune’s salt wash,” and “Tellus’ orbed ground, suggests that this play is out of time with the Court, and that the regicide it depicts is one that, as Hamlet sinisterly jokes, “touches us not” (3.2.235). All the while, the Player Queen responds to the Player King’s classicism in jarringly literal language, which seems to bring this play-within-a –play right back into the present. The Player Queen’s “sun and moon,” as opposed to the Player King’s allusive register, re-situates the language of the play in what Terttu Nevalainen might include in her discussion of the English “common core,” or words that maintain their currency across time. Then, too, the Player King’s own lexical pool contains words that mar the epic time-stamp of his lines with the stain of the present. The first cited use of “Orbed,” according to the O.E.D, is in 1598, rather contemporary with the period in which Shakespeare is writing. While “orb” as a noun has currency as far back as c. 1400, “orbed” as it appears here, as an adjective, is much newer in its use. And, perhaps most notably, “commutual” is a word appearing in English for the first time in this scene, which the Player King uses to describe the reciprocity of the marriage vow between the Player Queen and himself. The vexed time of the language, current language to describe what is supposedly guarded by the distance of the past, seems to aid Hamlet’s heavy-handed suggestion to his uncle that this play within a play has relevance in their present moment.

This diachronic (multi-chronic?) register of the language is complimented by Hamlet’s own performative presence in the audience. Ophelia, flummoxed by Hamlet’s malicious behavior towards her, tells him “You are merry, my lord,” and certainly Hamlet’s spirits seemed to be heightened in a way that allows him to assert his own presence as an audience member present to interject (“That’ wormwood!”) after the Player Queen’s poignant observations on widowhood: “None wed the second but who killed the first.”

But even beyond Hamlet’s heightened state of being in the play-within-a-play, Shakespeare plays with the tenses of the Player Queen’s lines on widowhood in the aforementioned moment. “None wed the second but who killed the first” contains a present and an implicit future tense, the idea that none wed or none will wed, as well as the passive “who killed the first.” This creates an interesting sense of time rhetorically in the sense that the Player Queen suggests that any current or future action is predicated on the legacy of an action in the past. We see echoes of such a philosophy in the Player King’s response to her when he says “Purpose is but the slave to memory.” Of course, the Player Queen’s meditation on widows re-marrying doesn’t end here, because she goes on to say, “A second time I kill my husband dead/When second husband kisses me in bed.” Suddenly, the action is all only in the present or future/conditional tense and the Player Queen’s lines, because of this tense shift, once again move the play within a play back into time with its royal audience.

These are some of the ways I’ve been thinking about language, tense, point of reference, and time in the passage, but I hope, finally that we can also think on the Player King’s fantastic discourse on “purpose” (mentioned in brief above), passion, action, and fate. When the Player King recites his lines on “purpose” being formed in “passion” but “passion ending doth the purpose lose” he offers up a provocative temporal model for thinking through action and inaction in Hamlet writ large, once again extending the play within a play from its distanced place in time to the immediate present of its audience. I personally found myself thinking on Munroe’s “Introduction: conceptualizing archaism” and her sense of the way in which the past forms presents and there is perhaps no present but presents past. I phrase this all somewhat abstractly here, but perhaps it is framed better as a question: in what ways is Hamlet’s psychological state, his action, and indeed his inaction predicated on his sense of the past? Can Hamlet act in the present? If so, what does it look like?

See you all soon,

John.