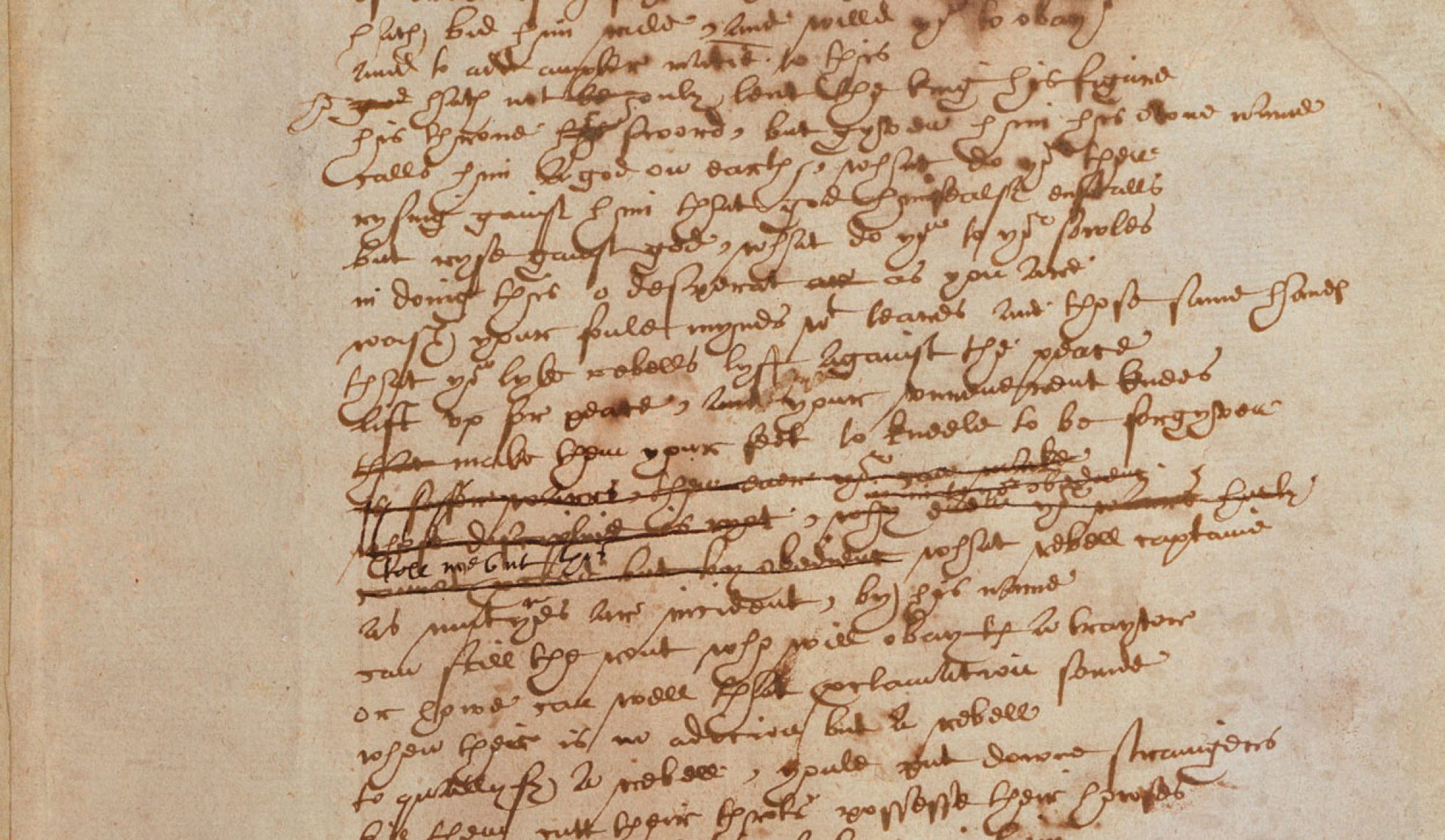

2.2.1-40: The Queen and Her Grief

Bushy

Madam, your majesty is too much sad.

You promised when you parted with the King

To lay aside life-harming heaviness

And entertain a cheerful disposition.

Queen

To please the King I did, to please myself 5

I cannot do it. Yet I know no cause

Why I should welcome such a guest as grief,

Save bidding farewell to so sweet a guest

As my sweet Richard. Yet again, methinks

Some unborn sorrow, ripe in Fortune’s womb, 10

Is coming towards me, and my inward soul

With nothing trembles; at something it grieves

More than with parting from my lord the King.

Bushy

Each substance of a grief hath twenty shadows

Which shows like grief itself but is not so. 15

For sorrow’s eyes, glazed with blinding tears,

Divides one thing entire to many objects,

Like perspectives, which rightly gazed upon

Show nothing but confusion—eyed awry,

Distinguish form. So your sweet majesty, 20

Looking awry upon your lord’s departure,

Finds shapes of grief more than himself to wail

Which, looked on as it is, is nought but shadows

Of what it is not. Then, thrice-gracious Queen,

More than your lord’s departure weep not. More’s

not seen, 25

Or if it be, ‘tis with false sorrow’s eye

Which for things true weeps things imaginary.

Queen

It may be so, but yet my inward soul

Persuades me it is otherwise. Howe’er it be

I cannot but be sad: so heavy sad, 30

As, though on thinking on no thought I think,

Makes me with heavy nothing faint and shrink.

Bushy

‘Tis nothing but conceit, my gracious lady.

Queen

‘Tis nothing less. Conceit is still derived

From some forefather grief. Mine is not so, 35

For nothing hath begot my something grief,

Or something hath the nothing that I grieve—

‘Tis in reversion that I do possess—

But what it is, that is not yet known; what

I cannot name, ‘tis nameless woe I wot. 40

I came to this passage particularly struck with the way in which figuration gives the Queen’s grief a life beyond the event from which it originates—Richard’s departure for Ireland. One way we might begin to discuss this is by directing our attention the use of personification in the scene. “Grief,” so says the Queen, comes to her as a “guest” displacing “sweet Richard,” her original “guest” whom she must bid farewell to. Personified, grief seems to stage an important process of exchange in the Queen’s own figuration of herself; she speaks of Richard metonymically as if he is part of her whole, a “guest” within the home of her inner being.[1] It is an odd moment, because in order for the Queen’s personification of “grief” and her metaphorical construction of “grief” as a “guest” to successfully pull off such an exchange (or is substitution a better word?), she has to disfigure Richard of his literal relationship to her as a husband and refigure him metaphorically as a “guest” to appease the economy of her figuration. Its all as if to suggest that, as the Queen at least would have it, the relationships one has with those populating the material world outside of our inner selves are figurative in nature, or depend on figuration to make them make sense to how we feel (this is merely a musing of mine, not a doctrine I’m married to).

In any case, the strange quality of the Queen’s metaphorical rendering of Richard accentuates how her sorrow increasingly abstracts itself from its literal referent in a way that creates an acute tension between what is real and what is not. The Queen herself acknowledges that she has no cause for grief other than Richard’s departure, yet she “cannot but be sad” (l. 30). This confusion is, importantly, the spark for Bushy’s remarkable discourse on the “substance of a grief” (l.14). Bushy also works within the figurative economy of personification in his suggestion that “sorrow’s eyes” blind us with their tears and thus “divide one thing entire to many objects” (ll.16-17). And yet here grief is no longer personified as a guest, but as a character who takes possession of the Queen’s subjectivity. This re-figuring of her optical consciousness in turn allows him to create an elaborate simile that relates her vision of Richard’s departure, already “glazed with blinding tears,” to “perspectives,” or prismatic glasses, which, when looked upon, reveal a confused assortment of images that suggest more than is actually present, those “shapes of grief more than himself to wail” (l. 22). Bushy in effect draws our attention to the way a figurative device like personification can take over our sense of the world and from there create multiple new images of the world that shroud over our fundamental sense of what is real and what is figuratively generated.

Yet, even Bushy seems not to be exempt from the powerfully confusing influence figuration can have over how one views the world. While Bushy feels confident in his claim that the Queen’s grief is “nothing but conceit” (l. 33), the reasoning of his “perspectives” simile is rather contorted and confusing. He claims that when “perspectives” are “rightly gazed upon” (i.e. looked on from directly in front according to our editor) they “show nothing but confusion,” and that it is when they are “eyed awry” (or looked at obliquely) that they “distinguish” their true “form” (ll. 18-20). Yet, he attributes the Queen’s unfounded grief to her “looking awry upon your lord’s departure,” thus finding “shapes of grief more than himself” (ll. 21-22). His logic thus seems to get lost within his own elaborate figurative construction since the Queen’s looking “awry” in the theory of prisms he sets forth should distinguish true and concrete reasons for grief, not the more vacant manifestations of it that she stands accused of. In total, Bushy is successful in establishing the vexed relation between figurative and real, but in doing so perhaps becomes a victim of that unstable boundary. Bushy’s confused simile, this is to suggest, stands as an example of the way figuration multiples itself as it gets engaged with; what begins as Bushy adopting the Queen’s own figurative trope of personification ends in Bushy ironically getting just as lost in the Queen’s grief as she is herself.

From this notion of figurative language and reasoning multiplying itself, I hope that we can also discuss tropes of the womb, pregnancy, and parentage, which pilfer this passage. These are tropes with their own figurative relation to the idea of a mood generating and re-generating itself, but of course are also highly gendered. The scene, as I have curated it, concludes with the Queen rebuffing Bushy’s assertion that her grief is “nothing but conceit.” It is, she says, “nothing less,” for “conceit is still derived from some forefather grief” (ll. 34-35). This is a great metapoetic moment in the play, which is full of conceit, and I am struck by the Queen’s familial structuring of how conceit works: it must descend from some literal referent, some “forefather,” in order to have “begot” the definite grief she feels, which in turn begets more abstract senses of grief in her. Then, to track back to the passage’s beginning, the Queen senses some “unborn sorrow, ripe in Fortune’s womb.” Here, she of course foreshadows Richard’s fall, but also interestingly incorporates her use of personification into the cycle of figurative parentage and re-generation that she espouses at the passages end. And, as one of the few female characters in the play, that her use of figuration should be so bound up with a maternal sensibility as well as establishing the plot to come generates a lot of interesting questions about how Shakespeare incorporates gender into the figurative economy of the play and the way in which the birth and re-birth of certain figurative tropes play with the bounds of literal and real so prevalent in this passage.

I hope this can get us started with this passage, see you all tomorrow!

–John.

[1] I cannot help but peripherally note the strange way in which we—or a least I do—often fall back on figurative language to describe figuration itself in expository writing. Such a phenomenon seems to double down on the way figurative language proliferates, or expands, outward as does the Queen’s grief in this passage.