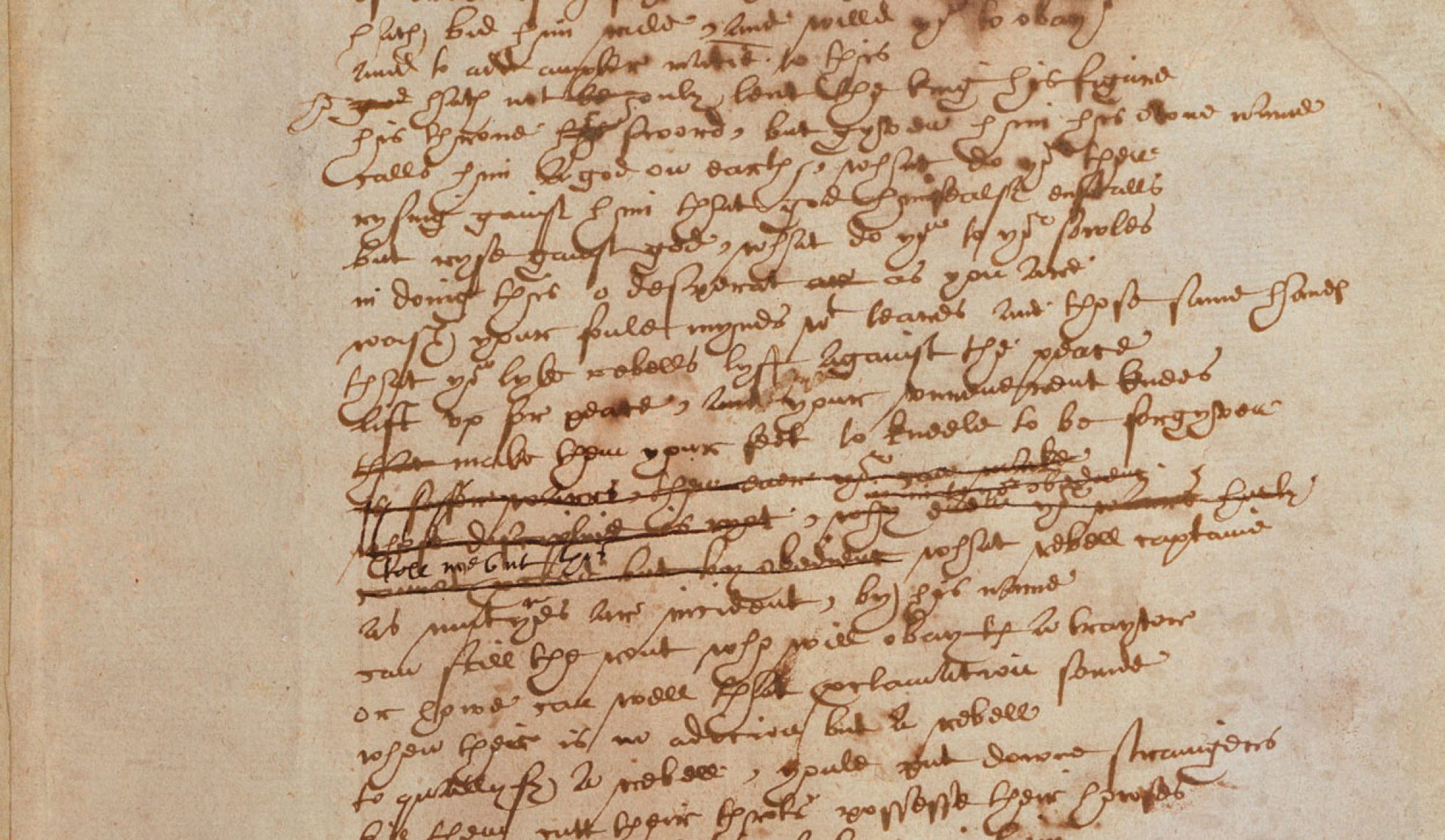

Richard:

Discomfortable cousin, know’st thou not

That when the searching eye of heaven is hid,

Behind the globe and lights the lower world,

Then thieves and robbers range abroad unseen

In murders and in outrage boldly here;

But when from under this terrestrial ball

He fires the proud tops of the eastern pines

And darts his light through every guilty hole,

Then murders, treason and detested sins,

The cloak of night being plucked from off their backs,

Stand bare and naked trembling at themselves.

So when… (3.2.36-47+)

Wait, what? If our own emphasis this week is on figuration, I thought this passage would be one to emphasize, for this epic simile takes its ornament to the extreme. The Christmas tree is all tinsel. Carried so far from common utterance that it doesn’t just deceive the ear but almost resists the intelligence, this transport might even require translation. The semantic skeleton, then (or trunk?—if I want to keep up my own metaphor), would read something like this: “As the sun gives cover to criminals here when it shines on the other side of the earth but brings them to light at dawn, so I….”

But grant Richard that he wouldn’t speak so plainly as I have, we can still see he doesn’t just rest content with elevation. Rather, he loads every rift with ore. Turn to his own language; consider this revision that keeps his lofty diction but excises the grammatically inessential:

know’st thou not

That when the searching eye of heaven is hid,

…

Then thieves and robbers range abroad unseen

…

But when from under this terrestrial ball

He fires the proud tops of the eastern pines

…

Then murders, treason and detested sins,

…

Stand bare and naked trembling at themselves.

Only about every other line is actually necessary to “the point”—unless elaboration is the point. What I want to think about, then, and hope we can talk about in class, is the way elaboration can be heaped upon elaboration, figure upon figure, the way an epic simile can set up a series of metaphors, the way metaphors themselves might host further metaphors, and the effect all this figuration has on syntax and grammar. At what point, too, does lofty language collapse under the weight of the decoration that gets it off the ground in the first place? At what point, that is, does this all become silly, more mock than anything else?

To point to just a couple of specific examples in this passage of its nested—or piled-up?— figuration: I’d note the metaphor (“searching eye of heaven”), personification (“murders, treasons and detested sins,” not “murderers”), and the transferred epithet (“guilty holes”). And speaking of silly, what even is a term for that ridiculous approach to diction that casts the earth as a “terrestrial ball”? It seems sort of like a metonymy. The “ball” could be an example of Burke means as the “realism” that metonymy shares with science. It’s so literal it’s figurative. But to me the word choice mostly aims to get as many syllables as possible out of any single signified.

I look forward to seeing what you all think of this passage’s excesses!

-Scott