The basic question of the function of language, or even what language is, was upon us this week, in particular what it means to say, on the one hand, that it is a medium of communication (playing out among talkers and writers), and on the other, that it is an expression of interiority, subjectivity etc. Related to but not identical to that question is whether we are to understand Shakespeare’s language as the activity of thinking, or the articulation of the already thought. Perhaps we also felt the undertow of another power—the “her” that carries us from the Forester’s “inherit” to the Princess’s “heresy” (4.1.20ff). Etymology? Sound? The word as materia?

We are not the first to ask these questions, of course, about Shakespeare and in general, and I hope we can (continue to) do some philosophy of language on the fly. It may be interesting, for example, to bring these questions into contact with Saussure and/or with Derrida. Jakobson will offer us more of a framework for next week. But I don’t think it will hurt to continue to excavate* the basic problems from the plays themselves. Our characteristic question is the double one of 1) how might such ideas about language get played out inside the plays, articulated by particular characters, implicit in certain discourses, and 2) how do they shape the way the plays sound as wholes, i.e., how do ideas about language feed back into the sound of language. (And vice versa; feedback is a useful trope here, an acoustic phenomenon that troubles cause and effect, even for the engineers.)

We have had a couple of specific versions of that problem, not on the level of philosophy of language so much as of models of language, grammar and economics. We asked last time about what it means when language in the plays seems to operate specifically under the aspect of grammar and grammatical transformation, and whether grammatical routines (conjugation, declension) might be taken up as shaping analogies for the plays at other levels of construction, e.g. the permutational character of a plot (two Antipholi and two Dromios, four lord and four ladies, etc.). With LLL we pondered the question of economics—Yan and Jeewon both raised interesting questions about the economy of the play and the kinds of exchange represented within it. Jeewon emphasized circulation, if I remember rightly; Yan asked, what does anyone get for it?

You could say that there is a closed, more or less self-sufficient economy in the marriage plot, four women, four men; that is one idea of what an economy is, a system for allocating resources that will always sum to zero. But in other ways the dramatis personae seems to be notably unparsimonious—take Holofernes, for example, who comes onto the scene only in the fourth act, introducing an idiolect that is in many ways redundant with Armado’s. Is the overplus of characters to be understood in relation to the overplus of language? Is Holofernes’s appearance a kind of symptom a) of that burgeoning language or b) of some other force responsible for both? In either case, do we count this (trying to stay within our economic conceit) as profit or as waste? Does the specific economic language of the play help us—small moments like the Princess tipping the Forester, or the large, if incomplete, structural gesture of the unsettled debt of Aquitaine to Navarre? (An incomplete ring structure, if you like.) At all events, again: economics as a discourse and also as a model for discourse. (We’ll have to sort out, too—perhaps when we get to Measure for Measure—what might be at stake in saying discourse as opposed to language.)

In passing: Eli suggested that one might pursue a psychoanalytic explanation for the above, in terms of sublimated and thwarted desire; and indeed, Freud’s basic psychic model is economic in terms of its dependence on a circulation of energies, with which each of us must do something.

Back briefly to my opening remarks in class about the five-stage process of rhetorical composition, inventio, dispositio, eloquentia, memoria, pronunciatio. I proposed it as a model of what thinking is like, for a well-trained schoolboy like Shakespeare and for some of his characters (well-trained or no). I want to keep that model in mind as we go. But I should say—it was on my mind after—it is by no means the only model of mind available in the period, with the most prominent alternative being the so-called faculty psychology, descended from Aristotle, which divides the mind into several discrete faculties, including imagination and understanding etc. That is not quite within our ken, but bears mention. The mind understood as a kind of back-formation from the practice of composition has a different status, not so much a philosophical account as an implication of practice.

One more general thought about all this, which is that—in asking questions about the way in which particular discourses can function as resource, medium, and model within this plays—we have on our side a couple of the great projects in twentieth-century literary criticism associated with the so-called linguistic turn:

- Structuralism: which is at its root an attempt to discover in a variety of other domains (e.g. kinship, narrative, etc.) structures analogous to those of language; the younger Roland Barthes is a useful example.

- Poststructuralism: which particularly in its Derridian or deconstructive versions finds language to be the medium of experience, characterized more by tropological excess and semiotic slippages than by the stability of its structures.

Two ways, that is, to think about what it means to take language as a model of (or in the second case perhaps of simply as) experience. Shakespeare, of course, is not obliged to commit himself to either view.

All this apropos of some great passages. Among many helpful things said, I think now of Madeleine’s observation about the Princess’s use of a maxim at a crucial moment—Shakespeare writes in a culture of commonplaces, whether the homely proverb or the elevated sententia, and it’s always interesting when characters have recourse to them. That the Princess might think herself alone at the moment when she depends most on universal authority is interesting and affecting. Was that (we went on to ask) a soliloquy or a fully social performance for praise? The general question in that passage of forbidding complexity was interesting, too—what kind of thinking is that? What does it sound like? Etc. I’d also like to pick up Whitney’s observation that the confusion around “remuneration” involved not only language use but language learning, even if Costard didn’t take exactly the right lesson. We might keep an eye on those problems as we go, e.g. the new speaker’s difficulty in sorting the particular and the general. I could go on…

…but as for the workshop, I thoroughly enjoyed rooting around in the day’s discoveries. I thought we went a good way toward establishing some of the tolerances of Shakespeare’s early verse, features like the occasional inversions in first position, still more occasionally after the caesura; a feel for where the caesura usually settles (he’s not afraid of putting it in the middle from time to time); something of the range of diction characteristic of different levels of style and characters; and so on and so on. My hope for that part of class is that we will just keep exercising our ears as we make our own imitations and weigh those of our colleagues. Questions of historicity are inevitable there, even though the syllabus supposedly defers them until the middle of the term. Jackie brought us up against them in weighing Mary’s phrase “that merry month and long.” While we wait for stylometrics and the history of the language to come to the rescue, you might, in moments of doubt, consult E. A. Abbott’s old but still valuable A Shakespearian Grammar, which is out of copyright and linked here; N. F. Blake’s A Grammar of Shakespeare’s Language is also a good source, though it lurks only in the library. Volume 3 of The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language can be consulted online, and is full of useful information.

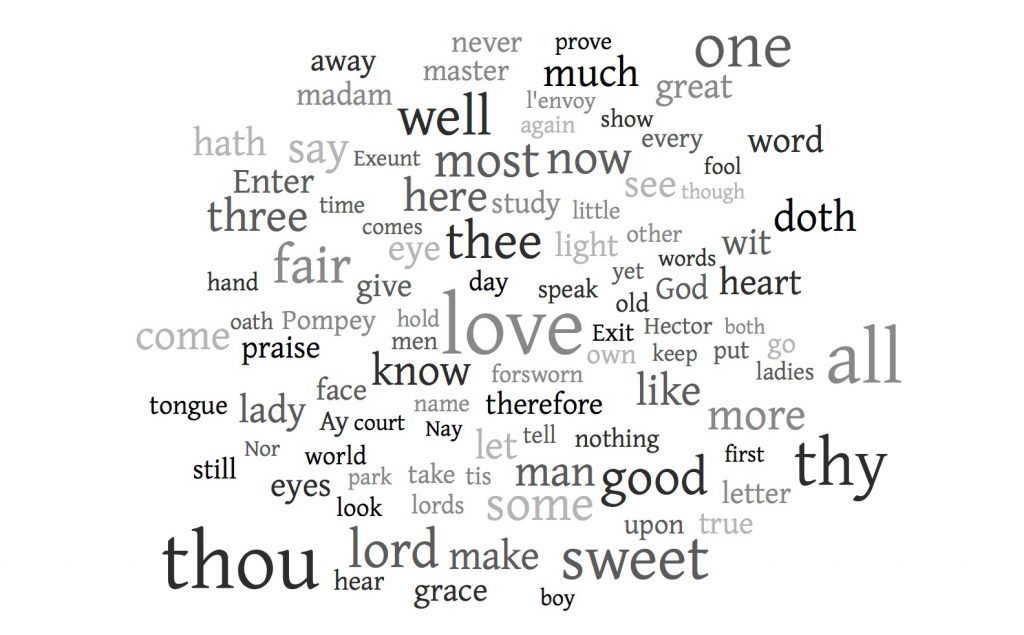

Finally, who was it who noticed the prominence of the word forsworn? Alex counted its instances at 16. That’s something we should keep listening out for, too, how particular words, or syntactic constructions, or schemes or tropes, become signatures of particular plays. I’ll close by anticipating our stylometrical investigations and posting below two word clouds, drawn from LLL and CE respectively. (I made them at worditout.com, but there are lots of sites that will do this if you give them a text; I took my text of the plays from Renascence Editions.) Here’s Love’s Labour’s Lost:

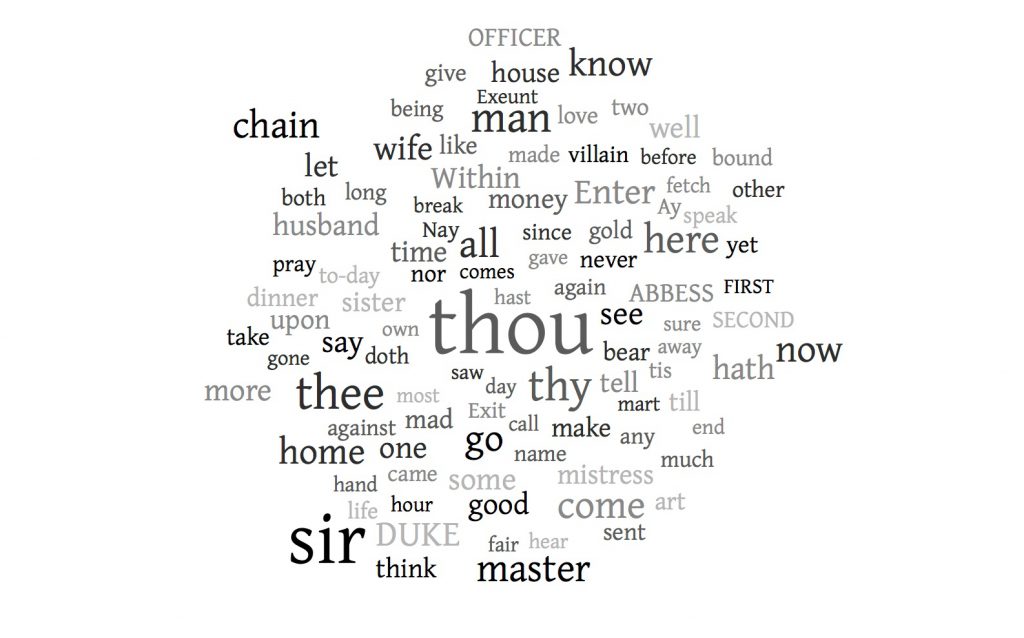

And here’s The Comedy of Errors:

Jeff

*Excavate? Why excavate? The word seems to assume that the answer lies deep down, underneath, etc. Should we assume that?