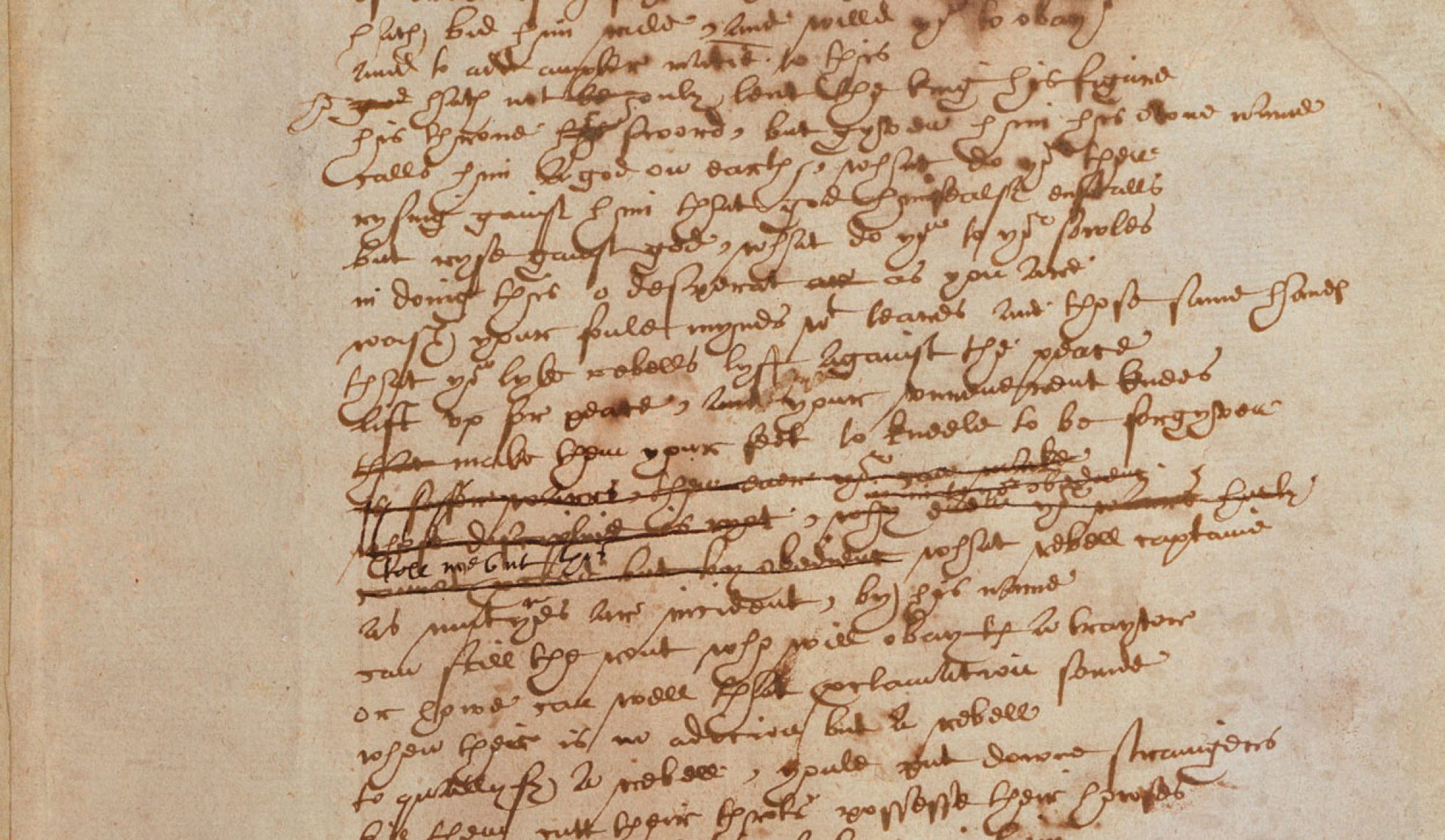

In Love’s Labour’s Lost, I feel that Biron’s profession of love to Rosaline in Act 5, Scene 2 is worth emphasizing for our upcoming discussion of rhetoric:

Biron:

“O, never will I trust to speeches penned,

Nor to the motion of a schoolboy’s tongue,

Nor never come in visor to my friend,

Nor woo in rhyme, like a blind harper’s song.

Taffeta phrases, silken terms precise,

Three-piled hyperboles, spruce affectation,

Figures pedantical — these summer flies

Have blown me full of maggot ostentation.

I do forswear them, and I here protest

By this white glove — how white the hand, God knows —

Henceforth my wooing mind shall be expressed

In russet yeas and honest kersey noes.

And to begin, wench, so God help me, law!

My love to thee is sound, sans crack or flaw.”

Rosaline:

“Sans ‘sans’, I pray you.” (5.2.402-416)

To get the ball rolling, there are a few aspects of this exchange that I think should be considered in the context of the rhetoric that we have been reading this week:

- Biron shifts from a high, relatively Latinate register toward the beginning of this passage, evident in words such as “affectation” and “ostentation,” to a lower rhetorical style, evidenced by “in russet yeas and honest kersey noes.” This somewhat demonstrates the spectrum of high, mean, and base rhetorical styles put forth by Puttenham, Wilson, and by numerous authors referenced in the chapter we read this week in A Handlist of Rhetorical Terms. Granted, Biron’s high (and low!) rhetoric is empty and shallow, which Rosaline points out moments before, “But that you take what doth to you belong, / It were a fault to snatch words from my tongue” (5.2.381-382), as well as above with her exasperated “sans ‘sans’, I pray you.” What Puttenham warns about borrowed language, that “generally the high style is disgraced and made foolish and ridiculous by all words affected, counterfeit, and puffed up” (p237), seems to appear in Biron’s speech.

- Moreover, Biron’s claim of parasitic “maggot ostentation” when referring to his previous rhetoric, especially when considered in the context of theft, may shed some light on a potentially troublesome and fraught relationship between languages, not only between but also within rhetorical styles. For example, Puttenham writes of “usurped Latin and French words” (Arte p231, see 36n). Do rhetorical choices illuminate persons’ understandings of how their self- and national-identity exists relative to their surrounding listeners?

- Biron’s presumably lower rhetorical style, which opens with “My love to thee is sound, sans crack or flaw,” is clear and monosyllabic, but can be viewed as rhetorically problematic all the same. For example:

- His usage of French socially elevates his speech (see line 5.2.416n in Love’s Labour’s Lost OUP) from what Wilson would consider plain to puffed up “ouersea language.” Biron thus seemingly undermines his own rhetorical project of lowering his register from “figures pedantical” to “russet yeas and honest kersey noes.”

- Yet, Rosaline’s response, “sans ‘sans’, I pray you,” reiterates Biron’s rhetoric for the very purpose of putting a stop to it, thereby legitimizing the utility of using “sans” to mean “without” here. Where, then, does Biron’s French rhetorically leave him relative to Rosaline’s dry humor?

I will provide a bit more detail on Wednesday to set up my (hopefully) more in-depth discussion questions, which will appear on a handout that I will bring to class. On said handout, I will also be bringing in some outside material and some etymological findings that may be fun to consider in light of the above.