Jessica Catalog Entry

Beyond the Wreckage

One of the major characteristics that sets Gardner apart from other Caribbean artists is that she self identifies as a white Creole woman. In this class we have studied black Caribbean experiences entirely, so to come across a Caribbean artist who is not black but white, was a shock to say the least. However, I believe that as an artist and a white woman, Gardner is in a unique position because she grew up surrounded by the aftermath of a catastrophe that her ancestors directly contributed too as beneficiaries of the slave trade and slavery in Barbados. Ultimately her engagement with black Creole subjects in “A Collection of Creole Portrait Heads of the Female Sex” is important because as a white woman she is subverting systems of knowledge and record-keeping that benefit her and reflect her history for the sake of allowing these particles, as Foucault calls them, to shine through. In his book On the Concept of History Walter Benjamin argues that the idea of history as a continuum of progress is false, but instead history is a non-linear compounding of wreckage that is perpetuated by the idea of progress. I believe that through helping these “Foucault particles” cast their glow, this particular piece is important because it reveals that coming into contact and reconciling with catastrophic history is important for the colonizing figure as it begins the process of sorting through the impounding wreckage and confronting the notion of progress as barbaric instead of futuristic.

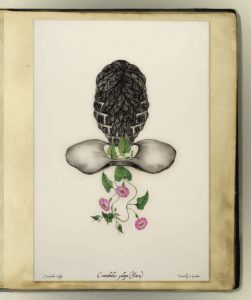

Using the term creole to describe the subjects of these portraits links the lives of these black women with Gardner’s own. This linkage acknowledges the inherent violence that typically is overlooked in popular uses of the term creole and instead foregrounds this violence as one of the conditions for creolisation to occur. Conversely, creolization is typically hailed as a progressive process because it speaks to discovery and the “creation” of something new from an amalgamation of practices and adaptation. This is evident in the different plant species that seemingly sprout from the bottom of the slave collar. On the one hand the discovery of these plant species and Thistlewood’s botanical obsession can be considered an advancement for white Creoles who can find productive use for them, but on the other hand, these plants can be used as abortifacients, which slave women would use, as Abba in Gardner’s portraits, to forcibly miscarry. In this way, this idea of progress cannot be wholly divorced from the idea of destruction, where the white creole disproportionately is on the side of progress and the black creole on that of destruction. By using creole identity to connect the histories of black enslaved creole women and herself Gardner acknowledges that the practice of progress is the cause for destruction.

After acknowledging this her role in the destruction, Gardner points towards the possibility of a future for these women, with the use of “contemporary Afrocentric hairstyles” as she describes in an interview. However, it is only after the acknowledging and sorting through this wreckage that she is able to arrive at the heads of these women, which seem out of place and disconnected from the plants and the collars whose shapes ultimately mirror their form. Both the hairstyles of these women and their aboutface positioning reveal that the future is a point of reckoning, where in spite of the destruction and attempts to control their ancestors bodies, there exists the possibility of a world where these women can deny the collisions with power that their ancestors were unable to avoid. By not providing the faces of the women, Gardner helps the audience to resist the temptation to give these women a story of our own choosing, the story of progress, heroism, and tragedy that we would ultimately want to feel better about Thistlewood and his brutality. In fact, this creates a sort of anti-portrait, allowing these women to escape the grasp of time, allowing them endless possibilities for whatever life that they are facing that is unknown to us. It is not just the audience that these women have turned their back on, but also Gardner herself. The very creator of this piece created conditions where her black creole subjects are not even beholden to her and her power no only as a white creole woman, but as the creator of the work as well. The shackles around their necks and the flowers sprouting from them are reminders of the catastrophic history connecting the fates of both black and white creole women. However, the physical heads being shown are where the black creole subject is allowed to exist in a realm beyond history and whatever our colonized imaginations would have produced otherwise.

Benjamin, Walter. On The Concept of History. Classic Books America, 2009.

Coussonnet, Clelia. “Exclusive Interview : Joscelyn Gardner – in the Framework of the Exhibition Who More Sci-Fi than US.” Art Cariben Uprising Caribbean Art, Electronic Eye, June 2012, blog.uprising-art.com/en/exclusive-interview-joscelyn-gardner-2/.

Vermeulen, Heather V.”Thomas Thistlewood’s Libidinal Linnaean Project: Slavery, Ecology, and Knowledge Production.” Small Axe, vol. 22 no. 1, 2018, pp. 18-38. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/689366.