Alejandro Catalog Entry

The two-page entry nearing the end of Joscelyn Gardner’s “A Collection of Creole Portrait Heads of the Female Sex,” relating to the slave woman Phibbah is of particular importance in this piece. Reading Thistlewood’s diaries, one notes the influence that Phibbah held over him during their relationship that lasted several years. Thistlewood’s modus operandi when it came to his sexual assault against his female slaves was to have long-term favorites while simultaneously engaging in multiple individual instances of rape. Phibbah was one of the slaves with whom the sexual relationship was long-term; the two had a child, “mulatto John” and she was even left with property after Thistlewood’s death as though they were married. Phibbah denied sex with Thistlewood ten times, a feat that no other slave woman accomplished once unscathed. The fact is, the power dynamic present is so stark and violent that any semblance of choice is illusionary. This in mind, however, Phibbah’s role in her destiny is obviously different than that of other slave women. Gardner’s work displays how even this relatively empowered figure is still framed in history and science as the lower, and it is only through careful critique that we can salvage some piece of these silenced voices.

Like all of the work, Gardner’s entry on Phibbah looks like a catalogue entry out of a colonial-era botany journal. Several stylistic elements contribute to the creation of this antiquated aesthetic. The lithographic prints, given their creation during the 18th century and subsequent fall, are purposeful. Other similarities to such journals of the age include the wax paper in place to preserve the plants and images, the font and diction of the all the included notes, even elements of the binding, paper, and bookmark mimic this style. The title, “A Collection of Creole Portrait Heads of the Female Sex,” also emphasizes the almost agricultural relationship the text has with its subjects, using dehumanizing jargon including “breeding.” In doing this, Gardner approaches two ideas. It allows us to acknowledge that we only have access to Phibbah’s voice, and of the other women, because of the way it came into contact with power and violence, an idea described by Michel Foucault in Lives of Infamous Men. Additionally, Gardner is connecting the academic flourishing associated with the Enlightenment and the Western canon with the brutality seen under colonialism and slavery. All too often, scholars of Thistlewood’s diary separate his violence from his more genteel intellectual pursuits. Gardner’s interpretation, however, outlines that they are in fact joint pursuits, one would not exist without the other. This idea is also held by Aime Cesaire in his Discourse on Colonialism, where he describes the brutalizing logic of the European enlightenment, predicated on the subversion of Black bodies. Gardner’s art shows how, to Thistlewood, the torture and rape of slaves was equal to watering the fields at the right time, an enlightened and laudable pursuit of domination over the “natural world.”

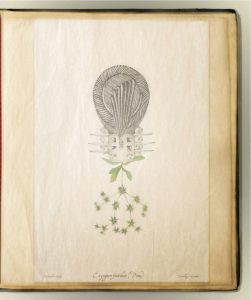

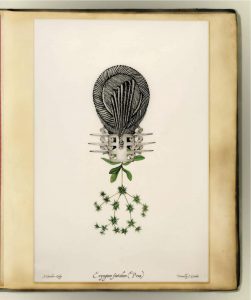

At the same time, Gardner’s work allows a subversive presence of Phibbah to shine through despite her relative lack of power, and return to her an individuality and an agency in her own story. We see none of the faces of the black women portrayed in Gardner’s work. No accurate likenesses have been passed down, so we are instead faced with an imagined portrayal of the back of their heads. Each of these heads has ornate braids and designs, so symmetrical and detailed that it is safe to say that none of the real women ever donned such a hair style. This imagined hair, however, is Gardner reclaiming the story from Thistlewood, allowing it another expression. The presence of the plants at the bottom of the heads also serves an important symbolic purpose. The plant beneath Phibbah’s head is Eryngium Foetidum, a tropical herb. These and the other plants illustrated were purposefully planted by Thistlewood for one reason, be it aesthetics or medicinal, but they were simultaneously eaten by slave women as abortifacients, in order to induce a miscarriage. In the context of Gardner’s work this serves multiple purposes, simultaneously displaying the power of other forms of knowledge creation while also exhibiting how high the cruelty imposed on these mothers was, so much so they would not want to bring their children into a world of slavery. It also shows that for all the book-keeping and classifications of Western society, there are modes of knowledge that will escape them, leaving reserves of power in the natural world for others to wield it. Other hints at the life that Phibbah led, apart from Thistlewood’s brutal impositions, are seen in the mentions of her eventual manumission (emancipation) and the notes about the life of her son. Gardner’s art brings to life both the brutal realities of Phibbah’s life while also unveiling an imagined voice, working to question our traditional notions of history.

References: