GABRIELE MÜNTER PHOTOGRAPHER OF AMERICA 1898-1900

The American photographs. Documentation and art.

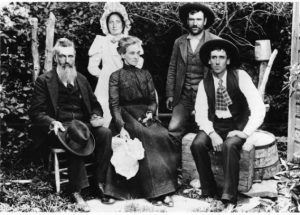

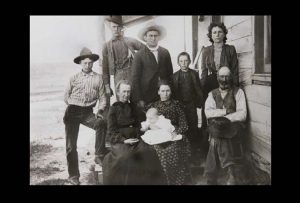

Münter made two often quoted statements about her drawing, and specifically about the drawings she made while in America – i.e. drawings made after her brief and unsatisfactory studies in Düsseldorf but prior to her taking classes with Kandinsky at his ‘’Phalanx” art school. The first appeared in a text of 1948, “Gabriele Münter über sich selbst” (“Gabriele Münter on herself”), 1 and the second in an appendix, entitled “Bekenntnisse und Erinnerungen” (“Confessions and Recollections”), to Menschenbilder in Zeichnungen, a printed collection of her later drawings, mostly from the 1920s, published in 1952. 2 In both texts she emphasized that she did not, as a young woman, think of her drawings as art, but rather as simple reproductions or records of her models, created in varying situations, and “with no goal in mind other than resemblance.” Thus she writes in the text of 1948: “My early inclination to make drawings came entirely from myself and received as little encouragement in my family as at school. When I was 14 years old, the accuracy with which I reproduced in simple outline the features of people in my environment attracted attention. On a two-year family visit [“Vetterlesreise” –“Little cousins trip”– L.G.] to the USA, I zealously made drawings of my relatives in my sketchbook, thinking only of achieving resemblance.” And four years later (1952), in the same vein: “Thus during my two years’ trip to the USA, I made drawings of the relatives of my mother, who had gone to the USA as a child but returned to Germany after her marriage, whereas all her sisters became Americans. I knew nothing at that time of art. I wanted only to grasp and record the people as they were.” (“Bekenntnisse und Erinnerungen”) The same idea is expressed yet again in a note prepared for the book Johannes Eichner, her second life partner, was writing about her: “I made counterfeit copies of all my relatives, the old folk and the babies alike. These are very factual works, far removed from any artistic structuring, but they have the advantage of offering living images of the individuals represented.” 3

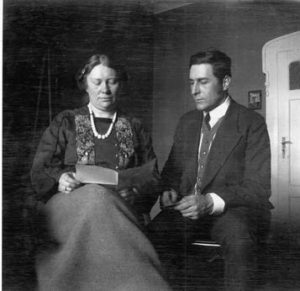

Even when she did take more trouble with a sketch and, for the larger ones, drew less spare, more detailed outlines and introduced some shading, Münter claims that she continued to regard her drawings as nothing more than true-to-life records of reality, which she had no desire to alter or add to but wanted only to set down and transmit as accurately as possible (fig. 91): “The portrait drawings faithfully resembling their models that I made in America in 1898-99 were the product of sound, accurate, and empathetic observation and an adroit and correctly transcribing hand – spontaneous, the work of nature.” 4

It may be that her insistence on her sketches’ not being “art” reflects a defensive modesty and insecurity not untypical of Münter.5 It should be noted, however, that her repeated disavowals of any artistic intention underlying her early sketching activity date from a time well after her years of study and partnership with Kandinsky and her association with the painters of the Blue Rider. Their implication is that, having become an artist, she inevitably pursued different goals from those she pursued naively and unreflectingly before she was aware of what art should strive to accomplish — goals defined not only by the members of the Blue Rider, and in an extreme form by Kandinsky, but by virtually all modern artists, especially, it should be said, in reaction to the spectacular rise of photography in the course of the nineteenth century. The artist’s goal, it was widely agreed, was to represent in his work essential aspects of reality that were not perceptible by the naked eye and to give expression to particular insights and experiences rather than simply reproduce visual appearances.

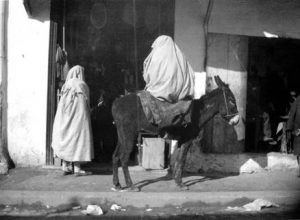

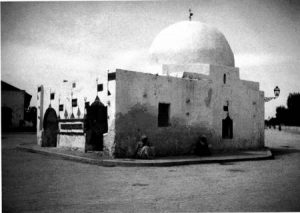

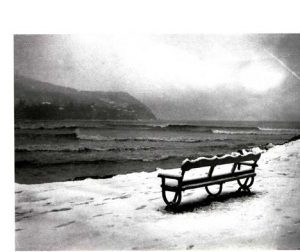

“Does this characterization” — i.e. of her sketching as strict copying without artistic intent – “also apply to Münter’s photographs,” Annegret Hoberg rightly asks, “inasmuch as the new technique per definitionem made a documentary representation of the world possible – one might even say, held out the promise of a purely documentary representation?” Münter certainly made apparently disparaging remarks about photography and, in contrast with her tolerant view of her own early sketching, judged it more harshly. Clearly, it was not naïve and it was not grounded in a natural gift like her sketching; it was a purely mechanical means of reproducing and fixing passing external appearances. “Photographs make clear how superficial, often even false, outward appearance can be,” she wrote in 1952. “The pertinent symbol must first be prized out of the changing views, the momentary, chance expressions. The laws of image-making wait for us to take up and structure objective reality.” 6 It is possible, even likely, however, that Münter had popular snapshot and even journalistic photography in mind in making this judgment, rather than photography as such. After all, her mentor Kandinsky had embraced the idea of photography as an art form even before Münter’s “Vetterlesreise” to America. 7 And over the years of their partnership, the two of them took many photographs. Like the carefully selected images of Tunisia or the Italian Riviera (figs. 66-71), Münter’s portraits of Kandinsky and members of the Blue Rider circle (figs. 72-81), are too meticulously posed and composed to be regarded as simple documentation. 8

In any case, Dr. Hoberg comes up with a surprising but convincing response to her own question. “If one compares the drawings Münter produced as a ‘humble dilettante,’ certainly not without talent and a personal signature, but without any strong and positive compositional will, before and during the American journey, with the independent drawing style of tersely meaningful contour lines that she developed a little later, it seems that photography contributed decisively to that development.” 9 In other words, it was precisely by way of her activity as a photographer that Münter learned to follow the “laws of image-making” and prize the pertinent symbol out of the external appearance. “Centering and focusing on the object to be photographed results in a definite tightening of the pictorial composition,” Hoberg explains, “whereby human figures — as is often the case with Münter — acquire, thanks to a slight lowering of the angle of vision, an unusual degree of plasticity and a well- defined position in the space of the picture.” 10 The text announcing the upcoming Münter exhibition at the Lenbachhaus is unambiguous on this score: “Gabriele Münter was a photographer before she was a painter. She took her first pictures around 1900, during a stay in the United States. [. . .] Photography was her first creative medium, a fascination that left lasting traces in her paintings; so a small section will be dedicated to the photographs she took in 1899–1900 during her trip to the United States.” 11

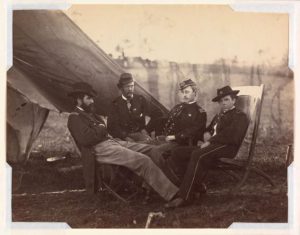

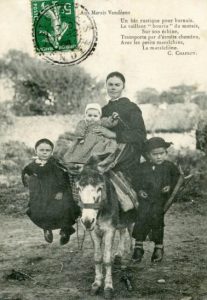

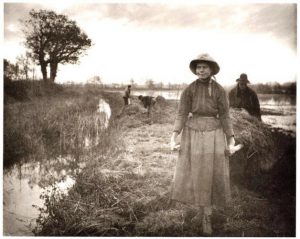

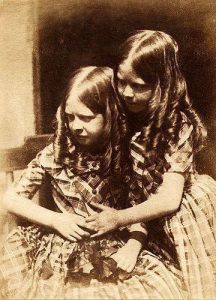

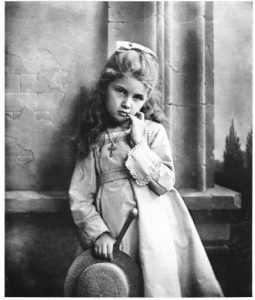

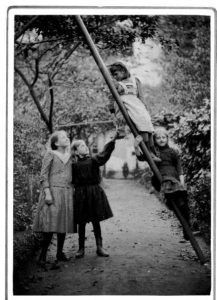

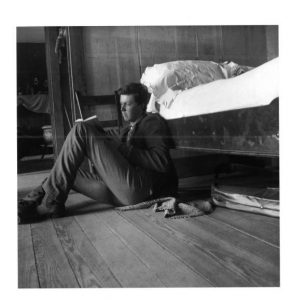

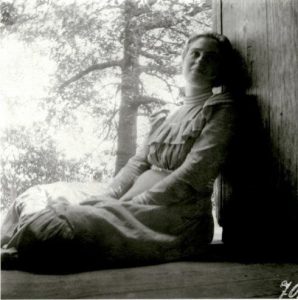

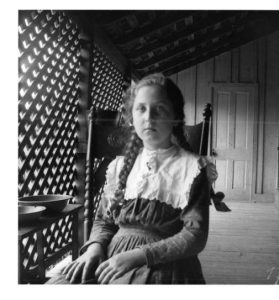

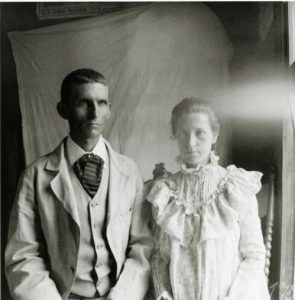

While some of Münter’s photographs do have the character of snapshots, many will strike the viewer as composed or pointed toward their subjects with some care. In an analysis of the three main categories of Münter’s American photographs – individual and group portraits, both posed and un-posed, landscapes, and scenes of labor – the art historian Isabelle Jansen emphasizes “their painterly and compositional qualities,” which “already point to the further development of a budding painter.” The posed portraits, Jansen claims, belong in a long tradition of portrait painting, while a photograph of a woman in a landscape holding an umbrella (fig. 88) could have been suggested by a favorite motif of some Impressionists. 12 Some of Julia Cameron’s photographs are obviously inspired by pre-Raphaelite painting (e.g. “Rosebud Garden” [1868] or “St. John the Baptist” [1872]). While this “painterly” approach to photography was severely criticized by other photographers, notably P. H. Emerson, Emerson was no less committed than those he criticized to the idea of photography as art.]

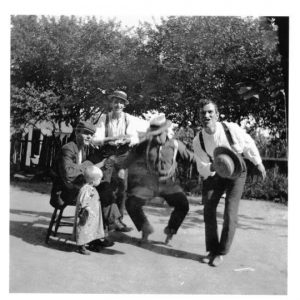

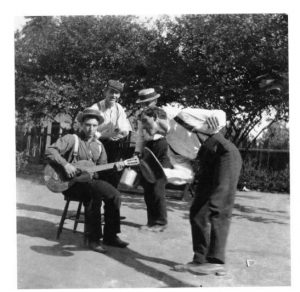

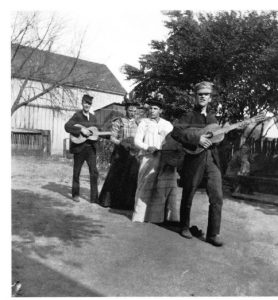

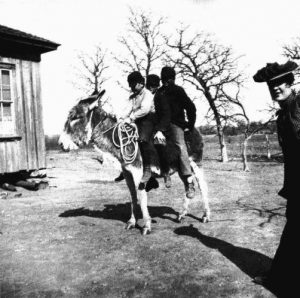

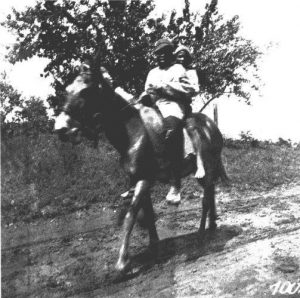

Even those photographs that purport to convey movement, it could be added, are distinguished by the arrangement and balancing of the parts in the space of the image, the relation of horizontals and perpendiculars, the interplay of light and shade. (Figs. 92-96)

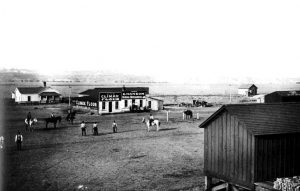

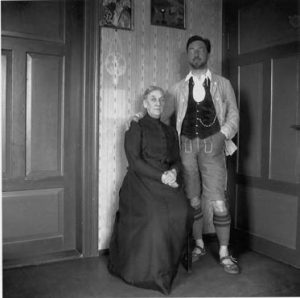

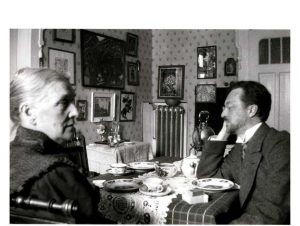

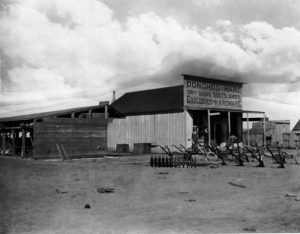

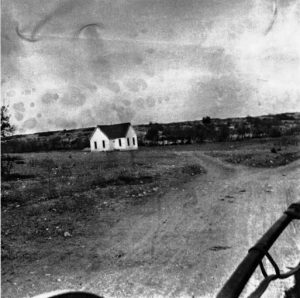

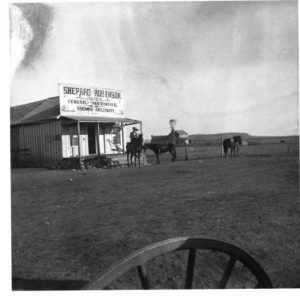

Münter’s aim, it might well seem, was to get, through her photography, to the heart of the rough, still largely undeveloped environment in which most of her American family lived and labored (figs. 57, 62-64, 97-99), and to convey something of the freedom and lack of constraint they enjoyed, 13 even while maintaining close family ties and personal dignity. (Figs. 52-55, 67, 84-88)

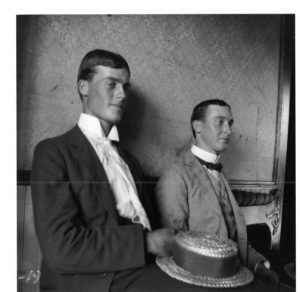

At the same time, her portraits of individuals are comparable with the work of many distinguished contemporary photographers: thanks to their beautiful and careful composition, they hold the viewer’s interest and arouse feelings of respect and admiration. (Figs. 55-56, 105-110) 14

Getting to what she experienced as essential about the world around her — a landscape, an interior, an object, a person – was her goal as a painter, Münter declared on several occasions. This meant doing more, she explained, than simply representing what her eye beheld or reproducing a sensuous impression; it involved a passage through her, a process of internalization and recreation. It thus overcame the separation and opposition of subjectivity and objectivity, interiority and exteriority, the “spiritual,” as Kandinsky would have said, and the material, in such a way that, in Münter’s own comments on the topic, “realism” (the meticulous “counterfeiting” of visible reality) was transcended by the representation of a particular artist’s experience and insight into the essence of a landscape, an individual, or a situation. Like the work of the great photographers since the invention of photography, many of Münter’s photographs, including the more carefully composed of those taken on the American “Vettterlesreise,” may well have been inspired, albeit not yet consciously perhaps, by the goal she later professed to have pursued as a painter. One is not surprised to learn from scholars who have closely examined her collection of photographs in the Gabriele Münter-Johannes Eichner Stiftung in Munich that she occasionally “improved” a photograph by cropping. 15 Nor is it surprising that photographs sometimes replaced sketches as the preparatory guide for a woodcut or a painting by the developing artist. 16

Münter could well have been aware, moreover, of the work of the numerous professional and gifted amateur photographers active in the nineteenth century, especially as a significant number of them, from the outset, were women, access to the new medium being considerably easier for women than access to traditional media, such as painting and sculpture — albeit the participation of women appears to have been less significant in Germany than in Britain, France, or the U.S. 17 Individual and group portraits (figs. 52-56, 100-110), people photographed next to their dwelling places or framed in doorways or windows (figs. 100, 107, 108), scenes of labor (figs. 61, 99), posed and un-posed photographs of children (figs. 65, 82, 108, 111, 114) — the types of image Münter produced with her simple Kodak box camera as she and Emmy traveled from place to place and family to family in the southern and southwestern United States — were among the preferred subjects of both professional and amateur photographers since the invention of photography in the late 1830s. (Figs. 116-134) Münter might also have had some knowledge of the intense ongoing debates about the status of photography: was it an art, as even a number of painters acknowledged, or a mere mechanical process, a typical feature of the more and more materialist and philistine society and culture that modern art was reacting against?

In sum, it seems not unreasonable to suppose that — even if unconsciously or without acknowledging it — Gabriele Münter, the aspiring art student and future associate of Kandinsky, Macke, Marc, Jawlensky, Werefkin, and Klee, did seek to take photographs that she and others would appreciate not only for their documentary value but as modest works of visual art revealing not so much passing external appearances as a particular and probing vision of persons and landscapes. For while they have certainly preserved a historically valuable documentary record of people and landscapes in the old South and South-West of more than a century ago, many of Münter’s photographs are also evocative of the inner experience of the people represented in them as well as of the inner experience of the photographer who selected, and to a non-negligible extent created the images. They thus offer the special satisfaction and pleasure that are aroused by any fine creative composition, any instructive or innovative ordering or re-ordering of conventional ideas and perceptions, and that have long been aroused by Münter’s work as a painter.

![Rudolf Dührkoop. Portrait of Alfred Lichtwark [Director of Hamburg Kunsthalle]. 1899.](https://commons.princeton.edu/munter/wp-content/uploads/sites/46/2018/02/117-277x300.jpg)